Fitness equipment has changed dramatically over the past quarter-century - but has it changed enough?

In the beginning, there was iron. Biblically speaking, iron begat free weights. Free weights begat selectorized weight stacks, which begat variable-resistance machines, which begat pneumatic-weight systems and other natural-motion machines.

By the late 1980s, strength-training equipment couldn't match the pizzazz of electronically controlled stationary bikes, stair climbers and treadmills - all of which helped spur America's cardiovascular fitness craze, a phenomenon that reached even greater heights with the 1995 introduction of a strange-looking yet revolutionary contraption called the Elliptical Fitness Crosstrainer ™.

Today, strength-training and cardio equipment work together side by side - if not literally, then at least figuratively - to help ensure healthy lifestyles for about 33 million users of commercial fitness facilities. The caliber of a fitness center's equipment now factors heavily into a student's decision about where to attend college, a senior citizen's choice of retirement community and a family's overall commitment to fitness.

The industry has come a long way since those dark days when fitness was considered a niche activity and actually frowned upon by some segments of society. "In the 1950s, it was taboo to strength train, especially if you were a professional athlete," says Dennis Keiser, founder and president of Keiser Corp., which introduced air-powered, low-impact strength equipment in 1978. "People were afraid it would make you muscle-bound and inflexible. Progress in this industry has been terribly slow."

That may be true, especially when you consider that the modern era of physical fitness was really launched less than a half-century ago, when the first selectorized weight machines were introduced in the United States. Years of product development followed - some of it originating from the same technology used to create telephone keypads and Pac-Man video games.

"I think the industry has matured," says Mark Verstegen, founder and president of Athletes' Performance (known until recently as Athletes' Performance Institute), a Tempe, Ariz.-based training facility for elite and high-performance athletes. "But some products have been new variations of the same thing."

That's why, during the first 10 years that Athletes' Performance has been in business, Verstegen has encouraged his clients to employ makeshift tactics - elastic bands connected to pulley stations for added resistance, for example, or heavy chains draped over stacks for extra weight - to make strength training more innovative, challenging and effective. "The strength industry started to build machines that isolated muscles using weight against gravity," Verstegen says. "But right now, we're getting back to integrating exercise across multiple points and planes at various modes and speeds."

Russ Squier, executive vice president of Fitness Products International, a strength equipment manufacturer, agrees. "The purist approach was to design equipment believed to provide superior results, regardless of how difficult to use or intimidating it might have been to the end user," he says. "It was a clinical approach that suggested there was only one 'right way' to perform an exercise for maximum results. Therefore, only one equipment design could provide this. What we have since realized is that this approach can produce a product that makes perfect sense in the research and development stage, but that people won't actually use."

Behind the scenes, too, changes have been rampant. Fitness equipment companies have switched hands (most notably and recently, the acquisition of Nautilus, Schwinn Fitness and StairMaster Health & Fitness by marketing giant Direct Focus, plus the pending sale of cardio equipment manufacturer Precor Inc.) and sued each other over patent infringements more times than is profitable for a trade magazine to mention. Attribute both of those developments to an increasingly competitive field.

"The level of competition in today's market is such that the manufacturing capacity far exceeds product demand," says Steve Rhodes, vice president of sales and marketing at Paramount Fitness Corp., which has been in the strength business since the 1950s. "There is now a combination of several large diversified and publicly owned manufacturers, some midsize companies and a large number of smaller manufacturers. This is certainly a much different scenario than what existed in the past. Each company must decide how best to go after the business."

Back in 1977, there wasn't much business to go after - and even fewer companies to pursue it. Although some form of free weights had been around since the 1700s, when legend has it that people placed rods between two church bells and created the first dumbbells, it would be centuries before people began to experiment with multistation weight-training machines that used selectorized weight stacks. At the time, dumbbells and barbells were the primary means of physical conditioning, and were used only by a select group of individuals who possessed an early grasp of strength training's benefits. Much experimentation went on at the same time and behind closed doors, and there is debate about who actually introduced selectorized weight equipment to the masses.

Some observers claim Harold Zinkin and Universal Gym Equipment were the first, while others contend it was Paramount or perhaps even some other company. The bottom line is that selectorized weight equipment revolutionized the industry.

Zinkin's multistation Universal machine, for example, featured separate weight stacks that moved up and down on steel runners and were adjusted using a weight key system. "If I'm proud of anything, it's that machine and the fact that there probably isn't one professional athlete in the world who hasn't worked out on a Universal at least once," Zinkin wrote in the prologue to his memoir, Remembering Muscle Beach: Where Hard Bodies Began (1999, Angel City Press).

But Zinkin's goal wasn't just to make strength training easier for the pros. He wanted to broaden weightlifting's appeal with equipment that was safer, more compact and worked every major muscle group.

Those goals - especially versatility for all users - essentially laid the groundwork for every successful piece of fitness equipment that followed. When Arthur Jones began marketing his Nautilus variable-resistance weight machines 13 years later, in 1970, it was with the intent of making strength training more accessible to all kinds of people. His first multistation machine consisted of a pullover and a pulldown bar that included a cam in its design, allowing for the greatest amount of resistance to be felt at the user's strongest point in the range of motion, and the least amount of resistance at the weakest point. Variable resistance, which permits a full range of motion throughout the user's strength curve, was not a new concept at the time. In fact, it was invented in 1898 by Hungarian Max Herz.

Together, Universal, Nautilus and other pioneering companies helped usher in an era of competition in the strength industry, leading to such innovations as easier-to-access weight stacks, smaller footprints and cable drives.

Other manufacturers expanded the concept of resistance training even further. Keiser Corp., for one, eschewed the idea of iron as the be-all and end-all of strength training. In 1978, the company debuted the first air-powered strength machines that used pressurized air, allowing users to change resistance in small increments, providing a constant variable resistance curve at any speed and eliciting no shock loading to joints or connective tissue. Today, each Keiser 2 1/2 -inch-diameter air cylinder produces more than 500 pounds of force with only 3 pounds of actual moving weight. Proponents of this low-impact technology say it offers more control, reduces the risk of injury and is less intimidating to beginners. Most of Keiser's competition thus far has come from Europe, while other companies have developed similar hydraulic systems using oil for resistance.

"I don't think there's any question that we were ahead of our time," Dennis Keiser says. "And that's not a compliment to us. The Edsel was ahead of its time, too. People would say, 'If Keiser is so good, others would be making pneumatic equipment.' So that probably worked against us more than it helped. Once the industry breaks its ties to iron, it can move ahead."

Keiser, not surprisingly, has seen his share of detractors over the years. But several studies have shown that power - which pneumatic technology measures by combining the speed of a movement with the amount of force that movement produces - is a better predictor of an older adult's ability to perform daily activities than strength. Because power is the key to performance, elite athletes have also subscribed to Keiser's theory. In fact, early on, the company focused almost solely on high-performance athletes.

Almost two decades after the first Nautilus machine debuted, Arthur Jones' son, Gary, applied the design principles he learned from his father to plate-loaded machines that eventually became part of the Hammer Strength line, which was launched in 1988 and began working its way into health clubs in the early '90s. The machines focused on body movement and muscle ability, and appealed to both athletes and non-athletes. They are widely credited with bringing Olympic-style strength training into the mainstream.

Selectorized machines with individual arm movements followed, allowing users to work in two planes of motion. Units with cables and pulleys - definitely not modern concepts, by any means - helped exercisers define their paths of motion and work multiple muscle groups simultaneously.

"I believe most people, in all walks of life, are more interested in performance than in which muscles they're using for a particular exercise," says Gary Jones, who still argues with his father about whose form of strength training is more effective. "Realistically, it's important to senior citizens to be able to put a suitcase in an airplane's overhead compartment by themselves. That motion is not really any different than the one Shaquille O'Neal uses to shoot a jump shot."

Hammer Strength also deserves a place in the pantheon of strength-training equipment evolution for pioneering the use of computer-assisted design programs. Gary Jones created a digital figure nicknamed "Reggie" - a proprietary, orthopedically correct, three-dimensional simulation of the human body used in the design of Hammer Strength products. Computer-rendered details about arc, weight, balance, movement of equipment and other information helped designers improve the machines' biomechanical accuracy.

Use of this technology spread throughout the industry, resulting in products with improved ergonomics, structural durability and aesthetic appeal. Paramount, for example, updated its design software in the mid-'90s to include anatomical data and motion technology similar to Reggie. "We could then place scaled human models of varying size and gender into CAD designs before building full-scale prototypes," Rhodes says.

In the middle and late 1980s, a handful of strength equipment manufacturers began introducing machines that used computerized resistance. Instead of weight plates, a computer-controlled motor, gears and an electronic cam provided resistance.

These pieces of equipment paved the way for further computerization in strength training, as companies created electronic-resistance machines that talked to exercisers. A series of fitness networks for both strength and cardio machines - FitLinxx ™ , Schwinn Fitness Advisor ® and TechnoGym ® , to name three - actually took that concept a step further in the late 1990s by using computers to teach skills and monitor individual development, and improve member retention in the process. Life Fitness at one time also produced its own network software for its machines, but like many other equipment manufacturers, scrapped the software business to team with FitLinxx and make their equipment compatible with that company's network. Likewise, many facility operators chucked their members' labor-intensive and outdated workout cards to latch onto the network concept.

Today, at least two of those ventures - FitLinxx and the newly named Fitness Advisor by Nautilus - have a presence in hospital wellness centers, high schools and YMCAs. FitLinxx, which now boasts compatibility with more than 1,000 pieces of equipment made by 35 different manufacturers, also serves a large number of health clubs, college recreation centers and military clients. "The technology is a little bit more expensive than people expected," says Bryan Bergland, director of operations for Fitness Advisor, explaining why some observers might consider this segment of the industry still in its infancy. "This is not really a mainstream thing yet."

Even Keith Camhi, founder and chief executive officer of FitLinxx, agrees that the market is a tough one, but that hasn't stopped the company (which claims to own most of the market share, anyway) from continuing to invest and innovate. In fact, FitLinxx is currently developing new products aimed at facilities with lower staffing levels.

There have been many more subtle changes in strength equipment, as well - from surprisingly small footprints and the use of powder-coated paint to the implementation of sealed ball bearings instead of wearable bushings (thereby reducing friction). Not all of these are improvements that the average user (and perhaps the average facility operator) may always notice or even understand, says Greg Webb, vice president of engineering and manufacturing at Nautilus. "They just know that it's an abdominal machine and that it feels good," he says, citing one of the industry's more popular types of machines these days. "It's a lot better than the machine they used 10 years ago."

The history of cardiovascular fitness equipment is much shorter and developed much quicker - but no less colorfully - than that of strength equipment.

In 1977, such companies as Quinton Fitness and Trotter (both since bought by other fitness equipment manufacturers) were making treadmills for other markets. Hence, the consensus among industry veterans is that the first pieces of cardio equipment to appear in fitness settings were stationary bicycles.

While the Lifecycle - now manufactured by Life Fitness - hit clubs in 1979, the product had been around in one form or another since 1968. That's when California chemist Keene Paul Dimick introduced an exercise bike with electronic data storage to help business executives improve their level of physical fitness and measure their progress. After several unsuccessful attempts to market the Lifecycle to corporations, physicians, dentists and airline pilots, Dimick sold the machine's rights to fitness pioneer Ray Wilson around 1973, who eventually partnered with Augie Nieto (who ran a small strength-training club at the time) to establish Lifecycle Inc.

The Lifecycle is widely credited with being the world's first exercise bike to interact with users. An "Electronic Coach" was mounted onto the handlebars of the first models, and users selected a resistance level. The device then programmed a 12-minute hill workout and measured pulse rate, pedal repetitions per minute and calories used per hour. Today, much more sophisticated forms of that console can be found on nearly all varieties of cardio equipment.

Industry technology vastly improved when Bally Manufacturing Corp., maker of Pac-Man and other video games, bought Lifecycle Inc. in 1984. Engineers from Bally's gaming division helped streamline fitness equipment technology - even introducing in 1986 video technology that allowed rowing-machine users to race against computer-generated images.

Despite its innovation, the Lifecycle initially didn't sell well at all, so Wilson and Nieto decided to ship free models - available at the time in bright yellow, blue, white, red and black - to 50 of the top health club operators in the country. That strategy worked, and by the early '80s, most clubs featured some type of stationary bike, be it a Lifecycle or a Schwinn Airdyne - which utilizes wind resistance and was introduced by the bicycle manufacturer in 1978. The harder an exerciser pedals, the higher the resistance becomes. Because the fan creates resistance with air, no friction is created, Schwinn says, eliminating much of the maintenance associated with more complex systems. Many variations of the Airdyne are still available today.

During the middle and late '80s, however, more complex systems began to dominate cardio rooms. Rowing machines, stair climbers and cross country ski machines became major product lines for such companies as Life Fitness, StairMaster, Star Trac and Tectrix - which introduced the ClimbMax stair climber in 1989, replacing maintenance-intensive chains with steel cables.

Today, semi-recumbent bikes are widely outselling both upright and fully recumbent versions, according to sporting goods industry analyst SGMA International. And clip-on or skin-sensor heart-rate monitors and controls are now practically standard equipment on all cardio machines and commonly alter the resistance or pace to keep the user's vital statistics within a prescribed zone.

At the dawn of the 1990s, home equipment maker Precor Inc. entered the club market with a series of preprogrammed treadmills featuring such innovations as Integrated Footplant Technology ™ (which replicates the slight speed variations found in a normal stride), the Ground Effects ImpactControl System ™ (which absorbs the shock generated by walking or running) and a patented self-lubricating bed/belt system. But it wasn't until five years later, in 1995, when Precor introduced the EFX ® 544 Elliptical Fitness Crosstrainer ™ , that the manufacturer brought new life to the cardio market with a no-impact, variable-stride machine that appealed to a wider range of users than ever before.

"We knew the elliptical would be a good seller," says Paul Byrne, Precor's president. "Did we know it would change the industry. No. In fact, it concerned us. It was so different at the time that we thought acceptance might be an issue." Acceptance, however, was almost immediate. The elliptical provides a lower perceived exertion than a treadmill or a stair climber, and the movable handles on many versions of the machine allow for a total-body workout.

Precor bought the license for the elliptical's design from Larry Miller, an engineer for General Motors who sent a video of the "very, very crude" machine to Byrne in 1993. (Miller still receives royalties to this day.) "I said, 'Oh, boy. That looks interesting,' " Byrne remembers. "We spent two years improving the design and then launched it."

After the success of the elliptical - which spawned many similar machines - the company gained a friendly reputation in the community of fitness equipment inventors. "We review tons of submissions - at least three a week - that just come out of left field," Byrne says. "And most of those products should stay in left field."

He cites an exercise bike that Precor made in the late '80s and early '90s that allowed users to race each other on a video screen using networking capabilities (similar to the early video-integrated rowing machines). But the product proved too costly for most facilities and was eventually dropped. Tectrix later expanded on that concept in 1994 with the VR (Virtual Reality) Bike, which also failed to take hold in commercial settings.

Life Fitness' Exertainment ® system for clubs, which essentially offered an exercise bike equipped with a Super Nintendo video game system and a personal television monitor, suffered the same fate in the mid'90s - despite having been available on Life Fitness home equipment for the previous three years. That was a "painful lesson" for the company, says Chris Clawson, vice president of Life Fitness' consumer sales and former business director for its cardio equipment. "We believed people wanted to play video games while they were on the machines," he says. "We found out that the Exertainment system wasn't going to get them on the machine if they didn't want to get on the machine in the first place. But it was an idea that led to some improvements."

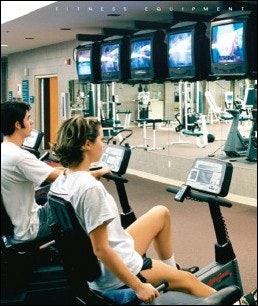

Indeed, because Life Fitness' system came equipped with channel-changing options, company officials discovered that while gaming wasn't the answer to alleviating boredom during exercise, watching television could be. New forms of technology offering users a variety of video, audio and cyber options soon followed - and were greeted with varying degrees of success. In addition to computer-based monitoring and tracking products like Fitness Advisor and FitLinxx, other products included BroadcastVision ™ and CardioTheater ® (wireless systems that allow exercisers to choose from several television or music selections), as well as NetPulse, which replaces the control panels on equipment with touch-screen color terminals featuring a high-speed Internet connection and a built-in CD player. Among the newest players in this market is Enercise ™ , which gives users access to a personal DVD player and screen attached to each piece of equipment, plus a patent-pending quick-change headphone jack that allows for no-time-lost replacement of the most-frequently damaged part on such systems.

Another technology-driven product that's been attracting some attention is the Trazer ™ , a virtual-reality exercise developed by Trazer Technologies Inc. that allows the user to serve as a joystick and control interactive video action by using full-body aerobic movements. Users move with the action on the screen while being tracked in real time by optical technology. Each wireless unit takes up less than 10 square feet of floor space and measures a user's heart rate.

Still, designers can take high-tech exercise equipment entertainment too far, says Fitness Advisor's Bergland. "When people go to work out, they go to work out," he says. "They don't necessarily need something to entertain them. They get enough technology at work. For some people, the club is a refuge from technology."

Verstegen, however, maintains that enhanced technology will continue to help create new user groups. "People learn and absorb information through technology," he says. "If we put people in an environment where they can interact and be in the game, we've tapped into their love of technology."

From its church-bells-as-dumbbells beginnings to the high-tech revolution of today, fitness equipment continues to evolve. In recent years, increased interest in aquatic fitness, yoga and Pilates, as well as a renewed attraction to such traditional equipment as exercise balls, medicine balls and modern pedometers, has bolstered the exercise movement.

Through all of these changes - some cyclical, some not - the goal that Universal's Harold Zinkin set out to accomplish 45 years ago has remained constant: Broaden the appeal of fitness to a wider range of users.

Up until two years ago, the fitness-equipment industry was as healthy as the lifestyle it promotes. Use of strength and cardio equipment increased by 69 percent and 41 percent, respectively, between 1990 and 2000, according to SGMA International. But between 2000 and 2002, the fitness industry - like most others - has been hit hard by economic recession. Even participation in running, walking, bicycling and swimming either remains flat or has declined. Still, the increased use of fitness equipment throughout the '90s is a testament to how evolved and effective machines have become during the past quarter-century.

Manufacturers say they have more new ideas in development. Whether they rival the impact of the first Nautilus machine or the elliptical, however, remains to be seen. "The basics never change," says Webb. "But you can certainly improve upon them and take them to the next level."