Strength and conditioning programs designed to help individuals overcome injury and disease are no longer the exclusive domain of hospitals

About two years ago, a breast cancer survivor asked Rose Nowak - a certified personal trainer and owner of Thunder Bay Recreation Center in Alpena, Mich. - if Nowak would develop a specialized program to help her get in shape after undergoing chemotherapy. "I did not feel I had enough background in that area, but I didn't want her to be left out, either," Nowak says. So she did some research on the Internet and found Eric Durak, an exercise physiologist who runs Medical Health & Fitness, a Santa Barbara, Calif.-based company specializing in developing cancer wellness programs at health clubs, YMCAs and fitness centers around the country.

Nowak contacted Durak and invited him to give a workshop at her facility about the benefits of exercise for cancer patients. She offered continuing education units to nurses and occupational therapists from area hospitals and clinics, and she contacted local cancer-support groups to encourage cancer survivors to attend. By the time Durak made it to town, Nowak had rounded up about 60 people - most of whom were unfamiliar with the effect that even a minimal amount of strength conditioning, combined with flexibility training and aerobic exercise, can have on cancer patients.

A study conducted by Durak in 1998 and published in the National Strength and Conditioning Association's Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, for example, revealed that a 10-week exercise program for cancer patients who had undergone radiation or chemotherapy helped them achieve significant gains in strength, aerobic capacity and quality of life. "I think by the end of this decade, we will see exercise rehabilitation for cancer patients become as popular as cardiac rehab," says Durak, whose programs are active in more than 130 facilities - including Thunder Bay Recreation Center.

In March, that facility began offering cancer wellness classes, which are held twice a week for about 75 minutes per session. Even though the program catered to fewer than 10 individuals early on, Nowak and two additional staff members became certified cancer wellness specialists through Durak's program, which is accepted by a variety of organizations including the American Council on Exercise, the International Sports Sciences Association and the American Kinesiotherapy Association. "Cancer is such a scary word," Nowak says. "People diagnosed with it tend to feel like they're doomed. We're here to show them they're not."

Nowak's facility is one of several around the country taking advantage of niche markets by targeting injury rehabilitation and disease recovery patients. "There's a gap between when someone leaves physical therapy in a clinical setting and when that person is ready to go back to a mainstream workout," says Michael Tabor, a physical therapist at Health Reach Rehabilitation Services Inc. in Brookfield, Wis. "There's definitely a market for that."

During the past decade, strength training for injury rehabilitation has broadened its scope to include people suffering from cancer, heart disease, diabetes, osteoporosis, post-menopausal symptoms, autism and other conditions. There's even evidence that suggests strength training can prevent injuries by reducing the probability of falls by older adults. "I think there is some resistance from club owners and fitness directors because they don't know these patients can exercise like other exercisers," Durak says. "Club owners have the misperception that they need specialized equipment. All they really need is a rudimentary understanding of the specific condition. Ninety-five percent of cancer patients would do very well with a daily walk, a fitness ball, three sets of dumbbells and some rubber tubing."

Specialized training and certification for facility staff members is crucial to ensure not only an understanding of specific medical conditions, but also to help avoid lawsuits. The hiring of additional staff might even be necessary. At least someone at the facility should know, for example, that a woman in breast cancer remission is not expected to gain back all of her upper-body strength, or that most cardiac patients should not swim.

Tom Baechle, executive director of the National Strength and Conditioning Association's Certification Commission, says he's seeing an increase in the number of employees at for-profit and nonprofit facilities seeking certification as either a strength and conditioning specialist (who works specifically with injured athletes) or as a personal trainer (who works with special populations). It's a trend he attributes directly to the increased attention facility operators are paying to the fitness needs of people undergoing rehab and recovery. This type of programming - if done correctly - opens new doors for people who previously may have found them shut. Not only might it generate great publicity, it'll probably also increase membership. Says Baechle, "When it comes right down to it, diversifying your options means diversifying your revenue stream."

When high school or college athletes, recreation fanatics or weekend warriors seriously injure themselves, they typically receive initial treatment in a clinical setting, often affiliated with a hospital or university. The same is true for older adults suffering from degenerative conditions or for industrial employees hurt on the job. Typical injuries include sprained backs, torn rotator cuffs and dislocated kneecaps.

Often, patients work with a physical therapist only until their insurance coverage for such treatment expires. "We try to get people rehabilitated 100 percent by the time they leave us," says Gary Shiffman, a physical therapist at Athletic Rehabilitation Inc. in Teaneck, N.J. "But insurance usually runs out before that, when they're maybe about 75 to 85 percent recovered."

Treatment varies depending on the nature of the injury, and the patient's age and physical condition. Some debate exists in the field about whether variable-resistance machines or free weights are more effective in rehabilitating injuries. Each method engages muscles differently, and the one used can depend just as much on a patient's abilities (and inabilities) as on a physical therapist's personal preferences and strength-training philosophy. "I'm in the train-muscles-not-movement corner," says Wayne Westcott, fitness research director at South Shore YMCA in Quincy, Mass. "How can you focus on an almost unlimited number of movement patterns. It makes more sense to start by training muscles - it doesn't matter where the injury is. Once someone gets his strength back in the core muscles, then we can work on isolating muscles."

Also frequently used are stability balls and balance equipment - products with which many patients aren't familiar until they undergo physical therapy. In fact, for nonathletes, physical therapy may be the first exercise these patients have in years - in which case any form of strength training would be new to them. "Some people are injured because they're not in shape," Tabor says, adding that it can be difficult to get patients to change their ways. "I help people help themselves. I'm going to give them the exercises they need to do, and then it's up to them to do them."

While many physical therapists encourage their patients to continue their rehab efforts by purchasing home equipment or becoming a member of a fitness facility, not everyone follows through. "Usually, the stickler is whether they're going to want to pay for it or not," Shiffman says. "Some of them realize that when insurance stops, life does go on without physical therapy." Of those patients who opt to continue treatment at a facility, not all are ready to work at the pace required by users of a busy circuit system, or they need additional assistance from staff members. To ease the transition of patients from clinic to club, some even house a branch of a specific clinic within their facilities.

When looking to diversify strength training programming options for special populations, consider the proven benefits of strength training for people with cardiac problems and cancer. These, however, are also groups that require careful supervision and more than a cursory understanding of specific conditions.

Prior to 1990, physical therapists did not recognize strength training as part of the recommended guidelines for rehabilitation of people with cardiovascular disease - the number-one killer in the United States, according to the American Heart Association. But today, resistance training for cardiac rehab has become one of the most common and popular forms of physical therapy for many of the 61.8 million Americans recovering from a stroke or heart failure, or suffering from high blood pressure, heart defects, hardening of the arteries and other diseases of the circulatory system. Researchers say strength workouts give patients the stamina they need to move through their daily routines. For example, strength conditioning has been shown to reduce demands on the heart when carrying groceries and playing with grandchildren. (Cardiac rehab patients are typically middle-aged and older; most children with heart disease can be cured with surgery, doctors say.)

Recognizing the crucial role fitness facilities could play in cardiac rehab, the American Heart Association and the American College of Sports Medicine in 1998 published recommendations for fitness facilities regarding the cardiovascular screening of members, appropriate staffing, emergency procedures and equipment. Two years later, the AHA and ACSM issued a position paper titled "Resistance Exercise in Individuals With and Without Cardiovascular Disease" that cites studies determining that mild-to-moderate strength-resistance training two or three days a week can increase endurance, reduce coronary risk factors and enhance overall well-being. And earlier this year, the AHA published a statement called "Automated External Defibrillators in Health/Fitness Facilities," which stressed the importance of AED placement and staff training in large facilities and those catering to special populations. (All three documents can be obtained at www.aha journals.org).

"It's one thing for patients who have heart disease to walk into a facility and exercise and not share that they have a history of heart disease," says Mark Williams, director of cardiovascular disease prevention and rehabilitation at Creighton University Medical Center. "It's another thing for a facility to accept patients with heart disease and not have a plan in place to keep members safe."

The AHA recommends that facilities have a written medical emergency response plan that is routinely practiced by personnel. Staff members should be certified in CPR; know how to recognize and respond to members' complaints of chest pain and dizziness; have a plan for who stays with a member in need until a medical team arrives; and be trained in the use of AEDs. (For more information on AEDs, see "Shock Wave," March, p. 55.) Shiffman also suggests keeping detailed documentation about each member's medical history and rehab/recovery process - just in case a lawsuit concerning a member occurs.

In 2000, University of Massachusetts researchers randomly surveyed 122 clubs in Ohio. They found that 28 percent of the clubs failed to pre-screen members for heart disease, and 17 percent of the total sample reported at least one heart attack or sudden death during the past five years.

Williams warns that the challenge of diversifying programs for a variety of special populations requires a level of commitment some facilities would be better off not making. "I have some concern about just telling clubs, 'Yeah, it's OK to start taking all the cardiac-rehab patients you can into your programs, because I have a feeling that may lead to revenue-generation abuse," he says.

Cancer patients, too, require a high level of commitment from facility personnel. Almost 1.3 million Americans are expected to be diagnosed this year with cancer, the nation's second-leading killer according to the American Cancer Society. But studies indicate that 90 percent of early-stage cancer patients will be (or are still) alive five years after diagnosis. The fact that such prominent athletes as cyclist Lance Armstrong, figure skater Scott Hamilton and baseball player Eric Davis have overcome various types of cancer makes "a very powerful statement for people who are trying to get back on track," Durak says.

Patients in chemotherapy become extremely debilitated, with some of them almost degenerating into a vegetative state, physical therapists say. "When they're here, they seem to get their energy back," says Tracy D'Arpino, associate research director and class instructor at South Shore YMCA, which offers a cancer recovery program.

Nowak says that one man has to practically drag his uncooperative wife to Thunder Bay Recreation Center's cancer wellness classes, but he knows she'll come home in a much better mood. People undergoing treatment in Nowak's facility share updates with the rest of the program's participants, and all of them are required to tell at least one joke per class. "I'm sure you've heard the cliché that laughter is the best medicine," Nowak says. "Telling a joke can actually take their minds off where they are, because even though they're exercising, they're still in a cancer recovery program."

Classes can vary in length and structure. While one-on-one instruction is ideal, two or three instructors are adequate for a class of three to five people. At South Shore YMCA, participants stretch and perform 10 strength-training exercises on a circuit system, doing 10-rep sets. Class participants at Thunder Bay Recreation Center use free weights and also work out on miniature trampolines and fitness balls, as well as do some aerobic stepping routines.

Thunder Bay Recreation Center offers eight weeks of classes (two a week) for free - the program is ongoing, so people can join whenever they want - and charges $3 for each subsequent class. Anyone who makes it through those first eight weeks has a daffodil (considered by many as the flower of hope) planted inside the facility's entryway in honor of his or her courage.

"When you have a life-threatening disease, you've got a lot of negative things going on in your life," says Westcott, who mentions hair loss as an example. "It's helpful to have something positive, too. There's camaraderie. They're all in this together. Maybe the average person doesn't need that psychological edge, but these people do."

Targeting other special populations - people with diabetes and osteoporosis, for example - requires additional training and patience, just like catering to cancer and cardiac members. Local physical therapists may be able to help facilities establish programs for these and other user groups, and some of them may even refer patients to those facilities.

Facility operators who offer programming for special needs members say they find the work both rewarding and challenging. In the case of injury rehab, they're helping people get back in the game and resume their normal physical activities. In the case of people with long-term illnesses or disabilities, they're simply providing an opportunity no one else will. "I have to clear my head, because what I have on my mind is not nearly as important as what these people have on their minds," Nowak says about preparing to oversee her cancer wellness classes. "I remember that, and that's what sometimes gets me through these classes."

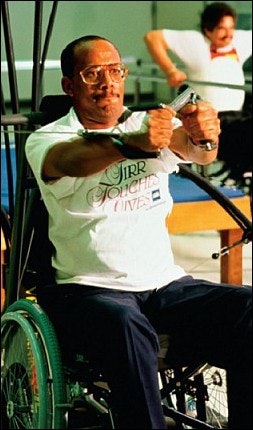

Westcott and D'Arpino have expanded their special-population programming to include classes for autistic children, cerebral palsy victims, blind people, obese people, victims of Alzheimer's disease, quadriplegics and others. Some of these groups, however, require specialized equipment - including bench-free flexible-resistance machines common in home gyms and clinical settings, wheelchair-accessible weight stations and an exercise bike for quadriplegics that uses a computer to stimulate a user's muscles so that he or she can maintain a specific pedaling speed. (Of course, any facility must be wheelchair-accessible to accommodate the users of this equipment.)

If a facility has space, its personnel should consider holding classes for programs that use traditional equipment out in the open. Many times, classes can be scheduled during lulls when the facility isn't busy. Specialized equipment, however, should be separate from other equipment simply so that other members don't use (or misuse) it. If the equipment isn't in its own room, signage explaining why the equipment is off-limits usually gets the message across to other members.

Another suggestion for implementing special-population programs includes organizing a small number of staff members (even part-timers) who regularly work with various user groups. Having a registered dietician on hand is also helpful, given the link between good nutrition and rehab/recovery. South Shore YMCA has about 20 volunteers who work with members in special programs, including patient caregivers and students from a nearby high school that offers a program in pre-physical therapy.

Finally, sessions shouldn't be limited strictly to strength and conditioning exercises. D'Arpino recalls teaching a young boy with autism how to walk and run on a track as part of the warm-up period for a strength session. "He'll never be able to walk into a gym and just train like you and me," D'Arpino says. "But now his confidence has soared." Another autistic boy avoided using the strength equipment during his first three sessions, she says. But then he realized how good the equipment made him feel, and now he has a hard time staying off the machines. "He's my star pupil," D'Arpino says.

Researchers, physical therapists and facility owners who work with rehab and recovery patients will attest that even a little progress is major progress. Lifting five pounds instead of four, after all, is a 25 percent improvement; lifting eight pounds instead of four is a 100 percent improvement. "What we're doing is really no different than what we do for our other members," D'Arpino says. "We're just helping them exercise, an opportunity they're not getting anywhere else."