Advances in automation technology offer recreation and fitness center operators new ways to save

Many fitness and recreation facilities have spoiled their members. Lights turn on automatically when a person enters a space. Room temperatures rise and fall to comfortable levels based on the number of people in that room. Heck, toilets and urinals even flush by themselves.

Facility operators have gotten spoiled, too, by the time-, cost- and energy-saving computer-based systems that patrons likely have come to take for granted.

Here's a tip: Now you can spoil your members (and yourself) even more. The building automation market is exploding, opening up any number of possibilities. According to one architect, recent advances in technology mean "any control sequence you can write down on paper, you can make happen through a computer." As a result, facilities can upgrade and streamline like never before.

For example, in addition to electronically maintaining a given facility via a central operator's workstation, individual panels representing every major piece of equipment (dubbed "smart panels" by some designers) can now be located in various equipment rooms and closets. From there, maintenance personnel (even an employee without a mechanical background) can monitor a particular function of the building to which automated control is distributed without traipsing all the way back to the central workstation.

"We see the day when control is going to actually be distributed to each individual valve and component," says Chip Berry, a principal with Cannon Design in Grand Island, N.Y., predicting that day might come within the next five to 10 years. "The technology is being used now in the automobile and manufacturing industries."

"Automation is the result of facility operators understanding more about energy efficiency and looking for cheaper ways to run things," says Carl Hurst, a Littleton, Colo.-based senior account executive for energy services and solutions with Siemens Building Technologies, which makes controls. "The bottom line is, you don't need to be running things when they don't need to be running."

Indeed, as budgets tighten and staffs shrink, the emergence of new automation technologies and other energy-saving equipment and ideas is even more important - not only to facility operators, but also to facility users. "More of the general public is becoming energy-conscious," says Jon Brooks, an associate at Beaudin Ganze Consulting Engineers in Golden, Colo. "People are willing to pay more to save energy. If there are two fitness and recreation facilities located right next to each other - with the same amenities and the same membership fees - and one has environmentally friendly, or 'green,' features, I think people would choose the green facility. Some people would even pay more to use the green facility."

While lighting and mechanical systems may be the most commonly automated features in a commercial building, designers, engineering consultants and automation-service providers can rattle off several additional possibilities.

"People can do ridiculous things with automation, automating anything they want to," Hurst says. For example, an office-building employee can scan his company ID card to gain access to the building, thereby setting in motion a series of commands that will send the elevator down to the lobby to pick him up, boot up his computer, begin regulating the air currents in his office, and even make his morning coffee. "Of course," Hurst adds, "there's only so much you need to do in a recreation center."

Still, many designers of fitness and recreation centers have found ways to improve upon the basic lighting and mechanical automation concepts. Most add to a building's up-front cost, but they also usually boast long-term, built-in savings.

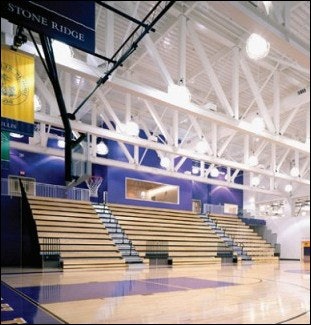

Lighting: Occupancy sensors, which detect the movement and/or sound of a person entering or leaving a room and then automatically turn the lights on or off, have become commonplace in rest rooms, classrooms, meeting rooms and limited-use locker rooms. So the next logical step for some facility operators may be placing dimming sensors in larger spaces. These devices work well in areas with abundant outside light, such as a natatorium, a lobby or a gymnasium having large exterior windows or skylights. Sensors detect when the sun goes behind a cloud and signal the lights to brighten. When the sun returns, the lights dim.

Because dimmable ballasts often cost about 40 percent more than standard ballasts, a less pricey alternative that approximates dimming is zoning light fixtures by row. Rows near the natural light source can be programmed to turn on or off, based on the location of the sun.

Another lighting-related alternative, primarily intended for an existing facility with large expanses of west-facing glass, is automated sunshades that unfurl when the position of the sun creates glare and excessive heat inside the facility. For new facilities, however, it would be much more feasible to simply opt for translucent panels or solid walls on the western side.

Mechanical: Because many facilities serve multiple purposes - college gymnasiums sometimes double as commencement halls and concert venues, and health club natatoriums host open-swim sessions as well as private parties - designers must create demand-control ventilation systems that know how to keep a space comfortable for 20 people as well as 2,000 people.

Because spaces are designed for a maximum number of people, the mechanical systems serving those spaces must bring in enough outside air to meet the maximum demands of that space. Carbon dioxide sensors, located in return-air ducts, detect the buildup of carbon dioxide in a given space and maintain a minimum amount of outside air until it senses more people entering the space, at which time it allows more outside air to be released into the room.

A related sensor, also placed in return-air ducts, controls relative humidity by detecting when humidity in a space is high and then cooling the moisture-laden outside air before mixing it with return air from the space. This is necessary because discomfort in a room isn't always related to heating and cooling problems; it could stem from humidification and dehumidification issues.

Other control options work best when the operator has a better knowledge of how many people will be in a specific space at a given time. For example, remote-access and web-based control capabilities now allow a facility manager to program the heat inside a natatorium to go on earlier than normal next Saturday because a local swim team needs to practice earlier than usual that day. Or an unusually long cold spell requires the building's heat to stay on longer after closing for the day to avoid frozen pipes.

Water: In addition to low-flow showerheads, toilets that flush automatically and motion-sensor faucets, some fitness and recreation facilities have redefined water-usage automation to not even include water. Officials with the city of Pasadena, Calif., and the Rose Bowl installed 259 waterless urinals in all of the stadium's public men's rooms last year, replacing 28 older, trough-type urinals. The move was expected to save the city more than 1 million gallons of water during five UCLA home football games and five home games of Major League Soccer's Los Angeles Galaxy.

The urinals look like standard urinal fixtures but use no water and have no flush valve. A cartridge installed at the base of the urinal acts as a funnel, allowing urine to flow through the sealant liquid and preventing odor from escaping. The cartridge also filters sediment, allowing the remaining urine to flow down the drain. Each cartridge saves more than 9,000 gallons of water and lasts for up to 7,000 uses.

Such systems have already been installed at universities, stadiums and arenas, parks and recreation departments, and school districts.

Practically every facility - with the possible exception of brand new ones - is ripe for streamlining its automation processes. All it takes is a commitment to saving money and electricity, plus a little creativity. "For the first time, energy customers have real energy options," says Mark Wyckoff, president of NiSource Energy Technologies, a Merrillville, Ind.-based supplier of distributed-power generation and storage systems.

Wyckoff's firm installed a co-generation mechanical system at the Breeden YMCA in Angola, Ind., last summer that uses natural gas to generate a significant portion of the facility's electrical needs. Energy created in the production of electricity is used to heat the Y's swimming and therapy pools, as well as provide hot water throughout the facility. A desiccant unit that cools the air through dehumidification is part of a planned second phase. The cogeneration system is expected to save YMCA officials 10 percent in annual overall energy costs.

In addition, the system's backup generation capabilities allow the facility to serve as a disaster-relief center for the community. The system is located in a 400-square-foot room that allows students, researchers and other interested parties to view and study the system and its controls.

Breeden YMCA officials received financial assistance through a major collaboration of business, community, government and university entities - including the U.S. Department of Energy, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the Build Indiana Fund, the Indiana Department of Commerce, Northern Indiana Fuel & Light and Tri-State University.

There are plenty of federal, regional, state and local programs available that reward green building designers and operators with grants, rebates and recognition. Some projects, for example, are made possible via Rebuild America, a U.S. Department of Energy-sponsored national network of community partnerships that save money by renovating buildings in order to reduce their energy consumption. In 2002, more than 500 Rebuild America partnerships yielded $300 million in annual energy savings, and officials are currently looking to incorporate more athletic, recreation and fitness facilities into partnerships. (For more info, log on to www.rebuild.gov.)

Another option for new building owners serious about going green is involvement in the United States Green Building Council's Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program. LEED is a voluntary, consensus-based national standard that emphasizes strategies for sustainable site development, water savings, energy efficiency, materials selection and indoor environmental quality. LEED facilities are commissioned by neutral parties and awarded special certification upon meeting specified criteria.

"LEED is definitely a buzzword in the architecture and engineering community right now," Brooks says, adding that he's currently working with some recreation clients considering LEED certification. The process is a costly one, though. Not only does it require expensive energy-saving equipment, it also costs extra to have the facility commissioned. (For more info, log on to www.usgbc.org.)

Most (if not all) states also have governmental offices that serve as lead agencies on energy-efficiency issues and often provide grants to assist in making commercial facilities greener.

Another source of information (and income) may be your local public utility company. Many cooperate with their respective state public utilities commissions to offer rebates to operators of new and existing facilities who choose energy-efficient equipment suggested by the utility. Often referred to as demand-side management programs, the rebate structures vary from state to state, but it's not uncommon for commercial facilities to receive several thousand dollars in rebates once they open and are operating efficiently. The most likely solutions include lighting and hot-water efficiency upgrades and air-conditioning unit replacements.

In Colorado, the first two facilities to take advantage of a new Energy Design Assistance program offered by Xcel Energy (which serves a dozen states) were municipal recreation centers still under construction at press time. Estimates have them consuming 16 to 19 percent less energy than if they were built only to standard code. Berry says the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, which offers a similar program, is involved in almost every project Cannon designs.

Private companies also offer assistance in the form of energy performance contracting. Some states currently have legislation that allows public entities to team with providers of energy solutions (such as Siemens, Honeywell International and Johnson Controls) to specify various types of energy-saving equipment for use in retrofit projects. The solutions provider puts together a design, installation and follow-up package that often includes items like an upgraded HVAC system, pool covers and low-flow showerheads. The money saved in energy costs will pay off the principal and interest from the equipment purchases; otherwise, the solutions provider picks up the difference. A financial institute plays a key role in the project, paying the solutions provider up front, while the facility operator makes amortized payments to the financial lender for a predetermined length of time.

One caveat: When considering available energy-saving choices - whether automation controls, co-generation systems or other equipment - it's best to err on the side of caution with regard to return on investment. A good return-on-investment period is usually between 18 and 36 months, and certainly no longer than five years, says Steve DeHekker, a vice president with Hastings & Chivetta Architects in St. Louis. "If you spend more money up front for energy-efficient equipment, it can pay for itself over time, and that's a good thing," DeHekker says. "You can also spend a lot of money up front and not ever have it pay for itself. That's not a good thing. Just because a piece of equipment saves energy and is theoretically less costly to operate does not necessarily mean it's the best choice. It then becomes a judgment call."

Consider such intangibles as equipment reliability and ease of use when determining what strategy is best for your facility. If a particular automated sequence or control has led to greater savings and user enjoyment in one facility, it may not have the same effect at yours. Take the time to find out what works best for your particular needs.

"Many of these ideas aren't new," Berry says. "But the ability to execute them is. It's made the job of many people a lot easier."