Using the latest in testing and monitoring equipment, fitness directors at clubs, rec centers, military bases and high scools are helping their customers get a better workout

There was a time when the success of cardiovascular exercise was measured in minutes, miles and pounds. Thirty minutes on the stair stepper four times a week, or four miles walking or jogging outdoors or on a treadmill three times a week, and you'd feel better and be healthier. You'd begin to be able to run farther or exercise longer, and you'd lose weight. An exerciser thus had two primary tools with which to gauge progress - the watch and the scale. Neither could be simpler to use or understand.

Times have changed. Fitness professionals and enthusiasts have gained in sophistication, as have the tools they use to set benchmarks and track improvement. Even the old tools have added features: Many state-of-the-art scales can measure the user's level of body fat using bioelectrical impedance analysis, and watches are available that keep track not just of time but of the heat index and the user's heart rate.

As assessment and monitoring technology that was once available only in hospital settings becomes more common at the local health club or YMCA, it isn't just triathletes who are measuring their progress in (for example) milliliters of oxygen consumed per kilogram of bodyweight per minute.

"There are so many people, weekend warrior-type athletes, who really put the time into training, and they want to know that their time spent exercising is quality time," says Michael Corrie, fitness director at U.S. Marine Corps Camp Allen. "Often, people who don't monitor their workouts exercise too hard or not hard enough. They end up spinning their wheels."

Heather Beller, health and fitness director at The Atlantic Club in Manasquan, N.J., is among many professionals who say it doesn't need to get any more complicated than monitoring one's heart rate. "I'm pretty much known as the preacher of heart-rate training," she says. "When I talk to people doing cardiovascular exercise, I ask them, 'What zone are you in today. What are you training for today?' Because otherwise, it's - well, it's not a waste of your time; it's good that you're exercising. But you should always be trying to exercise as efficiently as possible."

Naturally, there are naysayers. Jon Hinds is the owner of the Monkey Bar Gymnasium in Madison, Wis., and the son of Bobby Hinds, who has for 30 years been an outspoken proponent of a simple approach to fitness. Bobby's firm, Lifeline USA, is widely known for a product line that includes jump ropes, resistance cables, belts, straps and balls, and Jon's fitness center likewise features no weights or machines. As you'd expect, Jon Hinds - though he administers body composition tests with skinfold calipers, as well as cardiovascular, strength, jump, speed and agility tests - isn't a big believer in fitness assessment technology.

"I look at things differently," he says. "I always figure, 'Work toward vigor' - that's what Hippocrates said a long time ago. So I like to have people exercise until they're working vigorously, and then if they need to take a break, they can take a break. The technology makes an already simple thing complicated. Exercise isn't that complicated, and neither is nutrition."

Phil Lawler, head of the physical education department at the Naperville (Ill.) Community Unit School District, couldn't disagree more. Lawler thinks so highly of heart-rate monitors that he was responsible for purchasing 1,200 of them for his district of 18,000 students.

"On average, our kids use the monitors once a week, most of them twice," Lawler says. "It's the best tool in the world for monitoring exercise. I've been teaching for more than 30 years, and when we started using the monitors, it was the first time I could truly evaluate the kids in my classes effectively and fairly. Before then, I watched my kids work out and thought I could tell how hard they were working. When I got the monitors, I found out I had no clue how hard they were working just by looking."

As an example, Lawler recalls a female student who he watched run a 13.5-minute mile. "Run" is actually not an accurate term; the student barely ran, walking most of the course, slow jogging on occasion and breaking into a light sprint near the finish line. But when he checked her heart data, he was shocked to discover that her average heart rate during the 13.5 minutes was 187; during her last-minute kick, it shot up to 207.

"It was a real eye-opener for me; I thought, 'Holy smokes, I don't have an athlete in class who knows how to work that hard,' " he says. "Yet, in my old assessment of this girl, I would have gone to her, with good intentions, and said, 'You need to set higher goals and work harder in class.' And in her mind, she'd be thinking, 'I busted my tail, and he's going to tell me to work harder? Forget this.' "

Lawler says use of the devices has spurred students to learn about fitness and spurred Naperville's physical education department to reevaluate its program offerings, modifying them to get students more active while they play. Soccer, which Lawler says is misunderstood to be an aerobic sport, is now played five on five or four on four. Softball, about as non-aerobic a sport as any, is played four on four, with students coming to bat and running the bases more times in one class period than they might otherwise in three weeks' worth of traditional games. With both students and administrators working at it, kids are keeping fit: In a recent two-year study, just 3 percent of the district's students were found to be overweight or obese.

Heart-rate monitors and high schoolers might seem to be a strange match, but Lawler's other eye-opener was how quickly youngsters, even those in the fourth grade, took to them. Other potential user groups, however, particularly deconditioned, first-time exercisers, might find them more intimidating. "For those who don't need all the bells and whistles, it can be very discouraging," admits Beller. Beyond the most basic monitor that flashes beats per minute, most models these days allow the instant viewing of various bits of heart-rate information such as heart-rate recovery time and time spent in and out of your target zone - as well as options such as an alarm that alerts you when you leave your target zone. Beyond that, they can function as a stopwatch displaying various options such as lap times, and as a watch that displays time of day. Models for serious athletes come with an interval timer so users can fine-tune their workouts, and some (using an infrared device) can interface with a computer to allow the production of multiple reports and graphs for both heart rate and resting rate information analysis.

Oh, and don't forget the global positioning system. One new model includes GPS tracking so that runners can be as precise as possible with their pace, wherever they happen to be in the world (and so that mountain bikers or skiers can keep tabs on their whereabouts). In a similar vein, other models include an altimeter so that changes in altitude can be noted in the downloaded report of your 10K run, and a barometer so that - well, we're not really sure why.

Those aren't options typically selected by the kids back in Naperville - those flashing numbers showing how fast students' hearts are beating offer plenty in the way of feedback. Lawler says, "The best thing about having monitors is they took the middle to the bottom half of kids and gave them positive reinforcement that they'd never had before in physical education class."

In most settings, monitoring begins the first time a newcomer steps onto the fitness center floor. At the initial assessment, the customer goes under the figurative microscope - at a minimum, his or her weight, body composition, blood pressure, heart rate, bicep strength and flexibility are measured. Everyone benefits: For the customer, it's informative; for the fitness center staff, it's prescriptive; and for the facility owner concerned about liability, it's reassuring. For facilities short on help (heavily degreed in exercise physiology or otherwise), fitness assessment software packages abound that hook up to exercise equipment and offer a fully computerized evaluation, including a detailed health assessment and workout regimens.

Thereafter, users can hardly escape continued monitoring of their cardiovascular performance, with most units flashing heart rate, calories burned and distance "traveled." Then, a few months later, it's time for another assessment and proof that all that working out has been time well spent.

Most exercisers probably don't stop to think about just how those figures are generated, but the fact is that they're based on the averages of thousands of tests performed by researchers over the past couple of decades. Enter the user's weight, and the machine calculates calories burned by assuming the user's body-fat percentage is average. The number of calories burned and distance traveled will vary on different machines because of variables such as (on a treadmill, say) friction and stride length

"They're reliable more than they're accurate," says Chris Cramer, senior director of health and wellness at the Tuckahoe Family YMCA in Richmond, Va. "It's like having a scale that you know is off by seven pounds but don't know which way it's off. Even if you don't know the actual number, the reliability of the system is such that it'll show change."

The same is true, Cramer notes, not only of body composition analyzers - which ask a user to enter his or her age and in some cases measure the user's height as well as bodyweight - but of low-tech skinfold calipers. "You should be able to get a very reliable reading, but only if you are able to perform the test the same way each time," Cramer says. "The main benefit of having a testing system is that you don't have to have a highly skilled test administrator. Multiple people can test the same client, and probably get similar results."

Another huge plus for facility owners is that, as fitness assessment technology continues its forward march, administering tests has become a potentially lucrative revenue source. "You might think it's a fitness machine, but it's really a cash machine," is the way one new advanced system is being marketed, and that's as true for the manufacturer - which charges fitness facility owners $1,500 for on-site training in addition to the $7,995 purchase price for the most basic model - as it is for the facility owner, who might charge customers $50 to $75 for a fitness assessment. (Even if purchasing the most advanced model, a facility would have to perform just 270 $50 assessment tests to break even.) Another recent newcomer to the marketplace bears the slogan, "Presenting a Healthy Alternative to Vending," and suggests a nominal $1 fee to customers but provides space on the printed fitness assessment "receipt" for the sale of advertising. (The unit itself, which measures body-mass index, costs $6,000.)

It might seem dismissive to suggest that some of what is being sold is gimmickry, but even manufacturers suggest in their sales brochures that assessment systems are as much about selling the idea of fitness as they are about fitness. For example, a highly touted new product offers the same personal health and fitness profile and prescription, complete with colorful pie charts and bar graphs, as those generated by existing products. What's actually new is not the assessment, but how the assessment is quantified - one figure that represents the customer's "real" age, based on his or her results. But is telling a 44-year-old client that her "FitnessAge" is 52 more compelling or more scientific - or more comprehensible - than telling her she's 20 pounds overweight?

Says Corrie, "Having worked with the YMCA and with the Marines, I have seen that there is a distinct difference when it comes to exercise testing. The Marines come to me because they have to 'make weight' or improve their PRT [physical readiness test] score. In the YMCA setting, the general population expects the standard body-fat test, sit-and-reach test, step test and so on, and is happy with the nice color printouts and glossy pamphlets. I call this canned fitness testing, which is good for the customer in that you can show improvement. But for a 42-year-old housewife who has never engaged in cardiovascular exercise, who is huffing and puffing from walking to your facility from the car, the treadmill test is going to tell us what we already know, that she needs to improve her cardiovascular fitness and that she needs to lose pounds and inches."

Cramer says that in his YMCA setting, "probably 10 percent" of his members actively seek out fitness assessments, adding that "most of our people want to get in, do their thing and leave." In a recent month in which 220 new members joined, about half of them deconditioned, the staff performed perhaps 15 assessments. The reticence exists on both sides of the front desk, Cramer says - interest among clients seems to be limited to just "those who are really fanatical about exercise," while staff members prefer a more hands-on approach. "The Y nationally, and in Richmond especially, we're into the human touch thing," he says. "We'd much rather have a person administer these tests than have a machine do all the work."

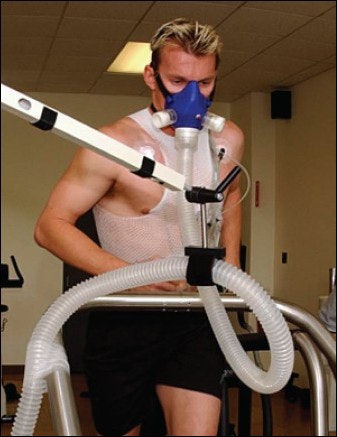

If measuring body mass rather than body weight represented a meaningful jump in the science of fitness assessment, the push toward metabolic testing is a giant leap. Formerly seen primarily in the cardio suites of hospitals, exercise science graduate schools and elite athletic performance centers, metabolic testing appears poised to revolutionize the nation's health clubs, Y's and rec centers.

Knowledge of one's VO 2 max - the maximum amount of oxygen the body can consume in a minute - is essentially what determines the efficiency of one's cardiovascular system. The test, though - it involves exercising on a treadmill or stationary bike, while breathing through a snorkel, until the subject is on the verge of collapse - is grueling enough that only young and extremely fit people try it, and typically only physicians or Ph.D.-level exercise physiologists administer it. In its place, assessment systems have long relied on a submax test, in which the subject exercises to within 70 or 80 percent of his or her maximum heart rate and the VO 2 max is estimated. That the maximum heart rate must itself be estimated first - the standard formula is 220 minus the subject's age - means that submax tests are, like many body-fat tests, more reliable than accurate.

"I've done a dozen max tests in my life as a subject when I was around 21 years old, and I was doing them with a good friend in school who was the same age, so our estimated maximum heart rates were identical," Cramer recalls. "Still, our true max heart rates were off by 15 beats or so."

Assuming that a test - or, more accurately, three separate tests - yields a good estimate, the benefits to the client are enormous. The object is to discover one's anaerobic threshold, or target heart rate - the point at which the body switches from burning fat stores to consuming muscle-stored energy in the form of sugars and glycogen (a starch that the body converts to sugar as needed). Exercising at or below one's target heart rate allows one to maximize the burning of fat stores. Exercising above one's target heart rate causes the body to produce lactic acids, causing muscle strain.

"With the new assessment systems, once you reach a lactic acid threshold it tells you the threshold has been reached," says Corrie. "And knowing this, you can write a very specific exercise prescription that lets the athlete know exactly where he or she should be training in order to improve aerobic capacity."

Adds Cramer, "I wouldn't say it's the wave of the future necessarily, but it's something that people are asking about as they get more serious about fitness. Anybody who knows his or her stuff in personal training and coaching can use it to his or her advantage, to prescribe exercise at a perfect level."

More data sounds good to Phil Lawler. Naperville Community Unit School District now has a medical advisory board that meets once a year. Last year, Lawler says, 45 doctors sat in, wanting to know what they could do to help improve the health of kids in the community. Thanks to Lawler's heart-rate monitors and the hospital-sponsored cholesterol screenings and body-composition tests performed during physical education classes, the school district knows more than most what needs to be done. "When our kids graduate, they get a 25page printout of their health profile," Lawler says. "In the future, I think within the next five years, we'll be e-mailing our fitness scores to family practitioners, because we've got better data on the kids than they do."

While Corrie is sold on the benefits of fitness assessment systems - "The future lies in this type of technology," he says of VO 2 testing - he's a little more circumspect about the dangers of over-reliance on numbers.

"People need to use these types of technologies the way a surgeon would use a scalpel," Corrie says. "You don't go in to see a doctor and immediately undergo a bunch of tests. They interview you, they find out what you're there for, and they use their tools to further hone their diagnosis. We're not diagnosing anything as trainers, but we're evaluating a person's quality of movement and the functional aspects of his or her cardiovascular system. A lot of trainers get involved with the technology and they don't really step back and understand how the client moves and what this technology is really going to do for him or her. When we think only in terms of what the computer tells us, we end up missing the big picture - and that is a disservice to those we are trying to help."