When outsourcing fitness operations, Jewish Community Centers must reconcile their nonprofit mission with marketplace viability.

Last April, the Flanzer JCC in Sarasota, Fla. - which had recently undergone a $1.5 million renovation that included an upgraded fitness center - closed its doors after more than 20 years of operation. In late 2006, the Sarasota Family YMCA stepped in and attempted to revitalize the 70,000-square-foot facility, which was in serious disrepair and bleeding $25,000 a week, but Y officials quickly determined that they would lose up to $800,000 a year by keeping it open.

Competition from other area fitness facilities simply proved to be too great, Y president and chief executive officer Carl Weinrich told the Sarasota Herald-Tribune at the time. "They've got a facility that's the wrong type of facility in the wrong place," he said. Added JCC president Marshall Klein, "It's a good idea that went bad, because it was set up as a business that couldn't be successful."

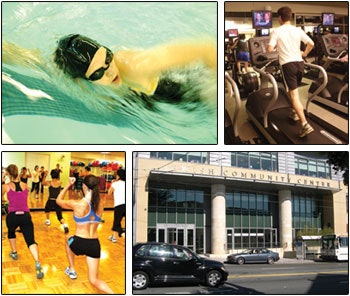

On the other hand, business is booming at the JCC of San Francisco, which opened a new $70 million building in 2004. The facility includes the 42,000-square-foot Koret Center for Health, Fitness and Sport - complete with state-of-the-art cardiovascular fitness equipment, specialized group exercise and strength training areas, a five-lane lap pool and a teaching pool, basketball and volleyball courts, physical therapy spaces and child-care facilities. In other words, it has everything you'd expect to find at a commercial health club - more, even. The Koret Center reportedly posts annual revenues in excess of $10 million, with more than $1 million from personal training fees alone.

Credit at least some of that success to the fact that the San Francisco facility was the first JCC to sign an operations agreement with a private fitness-management firm. The Bay Area-based Club One Fitness, which owns and manages health clubs and fitness centers in 11 states, has overseen development of the JCC's fitness center programming, operations and membership components for more than five years in exchange for an undisclosed management fee. Although there is no Club One branding, the Koret Center is fully staffed by Club One employees.

"The JCC owns the building and the brand, so Club One needs to fit with that," says Tom Nelson, director of community centers for the company, which now manages or consults with several other JCCs in the area. "We bring fitness expertise, but it needs to work within the JCC mission and integrate with the JCC team. We are, in every sense, part of that team. We are in managers' meetings and part of the staff environment. It's 100 percent integration."

"Club One set the tone" for this kind of joint-venture model, says Tom Maraday, senior vice president of New York-based Plus One Health Management Inc., which operates the fitness center at JCC MetroWest in West Orange, N.J., and does consulting work with a handful of other JCCs. (Other private firms also are involved in managing and consulting with JCC fitness centers, but they say confidentiality agreements prevent them from discussing the arrangements.)

The model, despite seemingly early success, has been slow to catch on. Only eight of the 200 or so JCCs in North America with a fitness component currently have official operating agreements with management firms, according to Steve Becker, continental consultant for sports and wellness for the JCC Association in New York. And he downplays the significance of what others call a "reinvention" of the 154-year-old JCC mission to offer educational, cultural, social and recreational programs for people of all ages and backgrounds. "Taking care of one's health is an important Jewish value, and JCCs have always emphasized physical fitness," Becker says. "Each JCC is self-governed, and we support them in their mission to provide the very best facilities and services to their members. Whenever an organization partners with another, there's a certain loss of control. The challenge is to work together effectively, so that both partners can fulfill their missions."

There's no doubt that a fitness-management firm can, indeed, bolster a nonprofit's market standing. Consider what Plus One accomplished during the first 12 months after it took over the management reins of the 20,000-square-foot Bildner Family Fitness Center at JCC MetroWest in late 2006: The facility's membership increased 28 percent to 4,100 memberships, which translates to a total of almost 10,000 individuals, according to JCC executive director Michael Hopkins. Meanwhile, the average monthly dues rate jumped 34 percent, and ancillary revenue per membership (primarily from a revamped personal training program) soared by 72 percent. Chiropractic care and nutritional services were added to the mix in an effort to promote the 130-year-old JCC's hospitality mission.

"At first glance, it doesn't look like a natural fit," says Plus One's Maraday. "We run corporate fitness centers and luxury spas. A lot of people asked what the heck we were doing getting into operating Jewish Community Centers. We've always followed this kind of model; we've just never had to execute it in this type of environment before. Internally, we knew that we could do it. But we had to prove ourselves, and there was a lot of skepticism from the JCC about our ability to go in there and get the job done."

Hopkins confirms that some of the center's employees and volunteers questioned whether Plus One's leadership would be worth the investment, failing to predict the uptick that occurred. But he says Plus One interviewed and ultimately retained about 100 of the JCC's 115 fitness staff members employed at the time the company moved in, keeping the transition seamless to members.

Internally, however, employees were less than thrilled about Plus One's incentive-based pay structure. "Plus One brought in a culture of management by objectives," Hopkins says. "Previously, we never had staff receive variable compensation. It was not part of our culture to pay people based on performance and incentives. Some employees said, 'Tell me my salary. Don't tell me you're going to pay me based on how many memberships or T-shirts I sell.' " In return, Plus One made some religious concessions, including a 1 p.m. opening time on Saturdays and a telephone greeting that begins with "Shalom."

Regardless of the compromises, the arrangement seems to work just as well for management firms as it does for JCCs. "It's a great business model for us, because we're able to take our best practices and help out the JCC as a partner, plus collect a management fee," Nelson says. "There is less risk, because we don't have the capital outlay we would if we were opening our own fitness center. We come in and we help our partner be successful. JCCs today understand that they need to think more like a business to be a viable organization. Many of them have gone bankrupt or have been on the verge of going bankrupt."

JCCs often fail for the same reasons other nonprofit ventures do, according to Caro. "It starts with the fact that they probably didn't do a proper feasibility study to determine if a fitness component could work in that location," he says, adding that administrators of nonprofits often overbuild and undercharge, both in the spirit of social goodness. "A not-for-profit should intend to make surplus revenue every year, so it has dollars to deal with unexpected deficits or to reinvest in the business. But a lot of them don't do that. They intend to break even, and sometimes they don't."

Club One, in a first for the company, is directing a team of St. Louis JCC-hired fitness employees at both campuses (rather than bringing in its own staff). It's a hybrid of the management firm's full-service arrangement with the JCC of San Francisco and a wholly independent operation. Nelson says Club One's role is to ensure consistency in programming and operations and to help employees focus on member acquisition and retention.

"The fact that we have so many facilities here would lead me to believe that there is a higher-than-average understanding of, and interest in, fitness," says Lynn Wittels, a former marketing director for Progresso soup who is now president and chief executive officer of the St. Louis JCC. "And that's good for me, because I don't have to sell people on the idea of a fitness center; I just have to convince them to switch from what they're doing and get them to come to the J, and I can do that. We're clearly not as expensive as many of the private clubs in town, but we're also not as cheap as the $19-a-month, 'here's a key, come in whenever you want but nobody will help you' type of club."

By hosting events like the Jewish Book Festival, which in November brought 20,000 people in 11 days to the St. Louis JCC (where membership is 35 percent non-Jewish), the agency maintains its commitment to educational, social and cultural programming while also fulfilling its fitness role. "Our members will only support us to the degree that we are equal to or better than the many other options that they have," Wittels continues. "We've rededicated this agency to being in a competitive position."

Unlike Wittels, Hopkins isn't exactly sure where JCCs fit into the overall fitness spectrum. "We obviously watch all of the other organizations and clubs that provide similar services," he says. "But we have our own plan and our own vision of how to serve our community." That includes active programming in the arts and for individuals with special needs. In January, JCC MetroWest rolled out a new scavenger hunt program designed to help introduce members to more elements of the JCC's mission. For example, attending a JCC-sponsored chamber music concert or Jewish film festival, scheduling a fitness-center orientation or getting a massage earns participants points and makes them eligible to win prizes. The more activities in which they engage, the better their odds of winning. "And the more touchpoints they have, the stickier their relationship with the JCC will become and the more likely they'll be to renew their membership," Hopkins says.

Club One's Nelson envisions more partnerships between Jewish Community Centers and management companies. "Some JCCs might just need us to come in and do sales or customer service training, or help with programming," he says. "The other end of the spectrum would be a full-blown management contract, where we take over everything, just like in San Francisco." Caro agrees. "There may be more connections like this in the future that might even start at the ground level, rather than later," he says.

Whether the business model will emerge in the YMCA world remains to be seen, because of that organization's structure of national governance. "But certainly other nonprofits, including community centers, are looking at this very closely," Maraday adds. (Last year, Club One began managing the 13,000-square-foot fitness facility at the India Community Center in Milipitas, Calif.)

"I truly believe that the blending of the soul of a great social-services agency with the discipline of a for-profit business venture is a great partnership," Wittels concludes. "No matter what we do that's good for the community, if we don't have quality business practices, we won't succeed. And then we won't be around to do all that good."