Rock climbers take safety seriously. Out on a rock face, they know that only three things stand between them and a catastrophic fall - their equipment (ropes, harnesses, carabiners, anchors and the like), their own skills and the skills of their belayer.

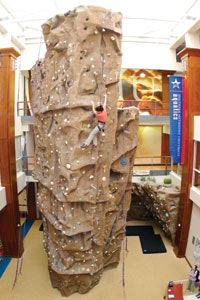

Photo of a woman scaling a large climbing wall

Photo of a woman scaling a large climbing wallRock climbers take safety seriously. Out on a rock face, they know that only three things stand between them and a catastrophic fall - their equipment (ropes, harnesses, carabiners, anchors and the like), their own skills and the skills of their belayer.

However, on indoor walls, where many people get their first taste of climbing and group rentals might represent one of the facility owner's major revenue streams, a climber need not find a partner to control the rope. That task can be capably handled by an auto-belay device, which allows a novice to climb without too much oversight, and a wall operator to limit the number of staffers on duty. While the use of auto-belays limits the number of climbers that can be on a wall at a given moment, it allows dozens more people to participate, with waiting climbers clipping into the devices immediately after others have enjoyed their slow, controlled descent to the floor.

Auto-belays are expensive (new units cost between $2,000 and $5,000 apiece) and require regular maintenance, but by all accounts, most purchasers installed them and didn't think too much about them. That changed a year ago, with the issuance of a "Stop Use" notice by MSA, one of the climbing industry's biggest suppliers of auto-belays, which was followed by MSA's recall of all Redpoint⢠Descenders and its abandonment of the climbing industry altogether. The ensuing confusion, anger and scrambling for alternatives on the part of wall owners - which was more than matched by other vendors' scramble to pull up the slack in the search for market share - have suddenly made auto-belays a central figure in discussions of climbing wall design, purchase, and research and development.

Owners of climbing gyms who consider auto-belays an affront to all serious climbers might have been snickering at the fallout, but the falls that led to it (one in Australia, one in Malaysia) were no laughing matter. MSA - a big name in industrial fall protection that had entered the climbing-wall market in the late '90s - worked with apparent diligence to pinpoint the problem. After issuing its stop-use notice in October 2009, its engineers tested the units, dismantled and rebuilt them, and retested them repeatedly, but couldn't replicate the fault in an attempt to find an engineering solution. According to numerous industry insiders (MSA itself declared that it would not issue any comments apart from its few official notices), the company couldn't see an upside to attempting to insure a product for which a potential failure risk was still of unknown origin. And, since its products had encountered no similar issues in the industrial arena - where fall-protection devices are not activated scores of times daily, as they are on climbing walls - MSA opted to leave the climbing industry, which represented only a tiny percentage of its worldwide sales.

The manner in which the company departed - by issuing an early December 2009 discontinuance notice and Christmas Eve recall notice, and offering, in March, reimbursements widely considered to be meager - infuriated thousands of climbing wall operators. But what was worse was the void left in MSA's wake. Wall operators who heeded the company's notices found themselves facing huge losses on their investments and continuing losses of revenue.

"When MSA left the market, people were pretty unhappy," says Bill Zimmermann, executive director of the Climbing Wall Association. "They were really slow to move from stop-use to recall, and then the terms of the refund were pretty bad. These things were expensive, and if you owned one of them for more than a couple of years, you basically got nothing. You paid around $2,500 for one of these things, and then $300 or $500 to have it serviced after a year, and you might have gotten $1,000 and no credit for the recent service or the parts they just installed in it."

"There is still a lot of resentment, because it's not a cheap product," adds Dan Griffiths, an owner of UK-based Applied Safety Solutions, which in the U.S. distributes (through Frederick, Md.-based SafeClimb, a division of Pyramide USA) the North Safety Auto Belay. "These products are rarely bought individually, so people had invested thousands of dollars in them. Imagine if your car was recalled, and the company never told you what was wrong with it and offered you next to no compensation. I'm pretty sure we'd all be annoyed. I have a lot of sympathy for the wall owners."

It is also easy to sympathize with those owners who opted for an inexpensive (but ultimately controversial) fix that emerged within a couple of months of MSA's freefall from the climbing scene. Doing business as Perfect Descent Climbing Systemsâ¢, Melbourne, Fla.-based OTE Services LLC (a former servicer of Redpoint auto-belays) began to offer replacement auto-belays through its CORE Recycling Program for between $400 and $700. (The company's standard auto-belays list for $1,725.) OTE's website, which has not been updated since last spring, does not spell out exactly what the company does to the Redpoint units (and OTE did not respond to an interview request), but several sources confirmed to AB that the program involves the repurposing of the auto-belays through the addition of a second brake system. Correspondence between a climbing wall owner and OTE obtained by AB suggests that the company (and its insurer) considers the CORE Recycling auto-belays to be new units because of the addition of the redundant braking system - and, indeed, several OTE competitors concede that the second brake could well solve the problem of an uncontrolled descent - but MSA's reaction was not very conciliatory. On June 30, the company released a statement emphasizing that the Redpoint units were being recalled, that a second braking mechanism wouldn't necessarily address the unidentified problem and that such retrofitted models would be used at the risk of the user. "Furthermore," the company pointedly stated, "such modification or refurbishment efforts of recalled products violate federal consumer product safety laws and place the refurbishment companies at risk of possible severe civil and criminal monetary sanctions."

Despite the reference to federal law, Zimmerman notes that the Consumer Product Safety Commission was not involved in either the stop-use notice or the (significantly) voluntary recall. In addition, there is little agreement on whether the addition of a redundant braking system using parts engineered by another fabricator constitutes a "refurbishment" or a new unit, as OTE contends. "MSA is not happy that they're doing it," Zimmerman says, "but I'm not sure they can stop them."

The Redpoint is not the only device of its type on the market. What it shares with other mechanical, friction-based auto-belays is its utilization of a system not unlike the disc brakes typically used to slow automobiles. Earlier, relatively infrequent incidents involving Redpoints soon after MSA's entry into the climbing market had demonstrated some of the drawbacks of any friction-based system - brake-pad wear and a buildup of dust created by the friction that could contribute to a "floating" of the brake pad, as well as potential wear to or stuttering of the unit's clutch bearing. These are, obviously, devices that for safety reasons require regular inspection, maintenance and outside servicing. (MSA's troubles eventually led it to recommend twice-annual servicing, where previously it had specified annual servicing.)

The North Safety Auto Belay is also a friction-based unit that is outfitted with two independent brakes. Like the Redpoint devices, the North device's design is small and modular, allowing it to be easily moved from one place to another on a climbing wall, shipped less expensively than other, bulkier types of auto-belays, and reengineered to accept future technological advances. Griffiths also touts the system's galvanized steel cable, which he says lasts longer and shows wear more clearly than nylon webbing and other materials, and its built-in counter that takes the guesswork out of determining servicing intervals.

One trouble spot, however, is the servicing interval itself. The device's user manual requires that it be serviced at whichever point comes sooner: Six months, or 120,000 clicks (which occur each half meter up or down a wall) on the counter. One trip up and down a 30-foot climbing wall (and walls generally are built taller each year) would equal 40 clicks, at which rate 30 climbs a day would necessitate costly and time-consuming servicing every 100 days.

SO TRU Trublueâ¢, which utilizes a magnetic eddy current braking system, is unique in the climbing industry.

SO TRU Trublueâ¢, which utilizes a magnetic eddy current braking system, is unique in the climbing industry.Griffiths concedes the problem. "As the device was sold in Europe, the 120,000 number coincided with an average gym owner getting six months' worth of use out of it," he says. "But now, we've sold some of these products in Japan, and the usage there is phenomenal. We talked to one guy who in three or four months had already seen a count of 450,000." Seeking a solution that wouldn't involve customers having to send their auto-belays back to the manufacturer on a monthly basis, Applied Safety Solutions is in the process of collating wear data on the various auto-belay parts on behalf of North Safety Products and Honeywell, its Holland-based parent company, to determine whether the 120,000-click or six-month recommendations could be extended.

The second of the three types of auto-belays available, which predate friction-based units in the climbing industry by around five years and came to climbing walls by way of the amusement industry rather than the industrial safety industry, are hydraulic rather than mechanical. First introduced by Extreme Engineering and Spectrum Sports Int'l (and still distributed by those companies, as well as by wall manufacturers Nicros Inc. and American Rock Climbing), hydraulic auto-belays utilize the same technology that lifts the beds of dump trucks or the blades of bulldozers - by pushing viscous fluid, or a mixture of air and oil, through an aperture.

Hydraulic auto-belays are large and heavy and can't be moved around easily, meaning that they must be maintained onsite, and they're not modular, meaning that potential future upgrades can't be retrofitted. But, says Zimmerman, "They're utterly reliable and really proven in terms of how many years they've been out there. They're not going to win any awards for innovation, but they're rock solid."

John McGowan, president of Eldorado Wall Company, has one reservation regarding hydraulics - in the event that the cord or cable stops retracting, and the climber continues to climb and then falls, the resulting dynamic shock load on the system could put the climber in jeopardy. The danger, he says, is that the devices (coming as they do from the amusement industry) aren't intended to meet industrial fall-protection standards. "Personally, I think it's a good system, even if I don't think it's engineered to account for that scenario," he says.

The third type of auto-belay, which was purchased by Eldorado from a New Zealand company and is being distributed in the U.S. by Eldorado, Entre Prises Climbing Walls (in the U.S. and, exclusively, in the UK), Rockwerx and Adventure Rope Gear, utilizes a magnetic eddy current braking system that has been used in train, roller-coaster and gravity-ride applications but is unique in the climbing industry. Called Trublueâ¢, the auto-belay is notable for its "soft catch," Zimmerman says, which contrasts favorably with hydraulic auto-belays. And, he adds, "There aren't any wear parts in the Trublue, so it's probably extraordinarily reliable, but it doesn't have a track record. In terms of testing, I think they've put close to a million cycles on this one unit in the New Zealand lab. It's probably the most robust technology available, but it's also new."

Its novelty hasn't stopped industry veterans, even Eldorado's competitors, from jumping on the Trublue bandwagon. Adam Koberna, Entre Prises' vice president of marketing and sales, says EP, though it "didn't want to go into the auto-belay business," thought highly enough of the device that it became not only its European distributor but its hub for testing and repairs there. "We went to New Zealand to see it for ourselves, and the units and testing facility are impressive," he says. "After the nightmare left behind by MSA, we saw it as a benefit for us to be able to offer and retrofit the product onto our walls for those customers who want auto-belays."

Russell Moy, president and CEO of Pyramide USA, sees Eldorado's potential success with Trublue as benefiting the industry as a whole, even as his company's sales of North auto-belays have risen dramatically.

"When I saw the Trublue's magnetic system, its non-sacrificial parts, I could only think that the future is down that path, whether it's in magnetic engineering or liquid engineering," he says. "It's a step in the right direction; I don't mind saying that. I think a number of companies are already developing things that will compete with it, and make a unit that's even lighter - it weighs 42 pounds - but this has to be the direction our industry takes, because unfortunately, we deal with a lot of end users who really have no awareness of industrial safety."

If there is a safety issue here - and there's some disagreement over whether a small handful of auto-belay failures constitutes a major safety issue - it's not the climbers who are the problem, industry sources agree. It's the mom-and-pop wall owners who don't follow recommended maintenance practices - Moy says he's shocked at how few of his new customers are responding to his frequent e-mailed, phoned and faxed reminders of impending recommended maintenance - and a North American climbing industry that hasn't collectively insisted on setting high standards for auto-belays.

The European Union has the CE mark (it stands for conformité européenne, meaning "European conformity"), by which manufacturers certify that, on their sole responsibility, the product meets EU safety, health and environmental requirements. North American manufacturers, meanwhile, must meet standards or recommendations (set by ASTM International or the CWA) for climbing walls and virtually every piece of personal equipment used by climbers - except auto-belays.

"It's kind of a ticking time bomb, in our opinion," says Zimmerman. "Eventually ASTM or the American National Standards Institute will step in and say that the friction-based units are fall-protection devices, the same equipment being used in industrial applications, and that hydraulic units also need to be certified for fall protection. The way these things always happen with regard to the adoption of standards, though, is that it takes an accident for someone to take a careful look at it."

And, Zimmerman adds, the number of new products entering the North American market in response to the Redpoint recall is making it that much harder for climbing wall owners to make informed decisions with regard to safety or maintenance - or any of the other issues that most of them were completely unaware of until the moment MSA issued its stop-use notice.

"It has been a difficult year," Zimmerman says, "and the dust hasn't settled yet."