Mega-gym proprietors bet millions on basketball and volleyball

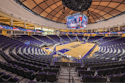

Photo of a basketball game

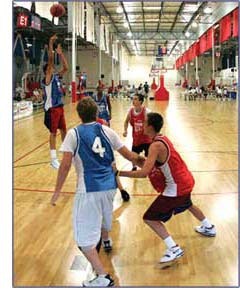

Photo of a basketball game

That this is often a recipe for business failure comes as something of a shock to newcomers to the sports industry. But that doesn't stop people from trying -- and the stakes are getting bigger. The past two years have seen the opening of Open Court, an eight-court basketball gym in Lehi, Utah, and Anaheim, Calif.'s 16-court basketball (or 22-court volleyball) American Sports Centers, a concept that its owners intend to take to at least six other U.S. cities in the future.

And yet, just a couple of states away from both of these recent ventures, there's one hoops facility (and the ghosts of two others) that could serve as a cautionary tale: The Hoop. The first of what was to have been a chain of urban gyms was built in Salem, Ore., the second in Beaverton. Just across the Columbia River, The Hoop came to Vancouver, Wash., soon after, the beginnings of what David Haas, general manager of The Hoop - Beaverton, calls "an aggressive campaign to go national, a $500 million business plan to expand into numerous cities throughout the country." Before The Hoop's owners would go forward, however, their plan called for the first three locations to become profitable. They didn't.

First came a shuffling of owners, then the closing of Vancouver's facility late last summer, followed a couple of months later by the closing of the original Hoop in Salem. That makes Beaverton the sole survivor of what was once a pretty grandiose plan. "I haven't seen too many of these facilities work with strictly gym rentals or basketball. At least, the ones I'm aware of have failed," Haas says. "And I get calls from all over the country. People see our web site and they want to talk to me because they want to do this in different places around the country. I tell them the reality, which is that these facilities are tough."

Mike Gallup, general manager of American Sports Centers, says his Anaheim facility has two things that most defunct gyms didn't: Size and anchor tenants. Size -- in this case an amazing 150,000 square feet -- he says is important because it allows the gym to support a variety of ancillary spaces (leased office and retail space, a cafeteria, a fitness center and an educational center for young athletes) that smaller facilities can't. The office space in particular, he says, "is a steady flow of money each month that you can count on, whereas court time can fluctuate from season to season."

But the anchor tenants -- National Junior Basketball and the Southern California Volleyball Association, which has moved its headquarters into an office suite within the facility -- are even more vital. "You've got to have the court time sold before you open up," Gallup says. "The highway is strewn with people who have done otherwise. If you tried to do this by depending on the guy down the street to bring his 10 kids for games, you'd go crazy trying to keep the courts booked, and you'd need a full staff of accountants to oversee things."

Facility operations specialists familiar with various recreational facilities say there's a danger in depending too heavily on one or two large groups -- they could move on in the event that another, more desirable facility opens. Gallup says his facility's size and relationships with these types of large organizations preclude another facility opening anywhere close to his -- even another of the American Sports Centers. "We could not put another one of these in Southern California," he says.

The dangers go beyond the choice of tenants, however. For example, one consultant who prefers to remain anonymous says that the blind spot in many feasibility studies can be blamed on myopic end users. "When we go into communities, we run into a lot of families who are really into a particular competitive sport, and they invariably overstate the market," he says.

Ron Vine, president of Olathe, Kan.-based Leisure Vision Inc., believes that larger facilities focused on volleyball and basketball may be successful in some markets. However, he sees the development of a functional pricing structure as a particular challenge for these types of facilities.

"Revenues per square foot of space are generally lower for basketball and volleyball programs and activities than some other activities, particularly fitness," Vine says. "Since many communities establish their fees for basketball and volleyball programs based on recovering the direct costs for the programs, and do not include in their fees indirect costs, private facilities that need to pay all indirect and direct costs through fees are going to be competing with lower-cost alternative providers."

But, notes Ken Ballard of Highlands Ranch, Colo.-based Ballard*King & Associates, facility operators that offer an array of quality basketball and volleyball programs (and not just open gym time) have a leg up on their nonprofit competitors.

"People will spend any kind of money for their kids to participate, especially if it's a good facility that has good programs," Ballard says. "With the growth of girls' sports, many of these youth sports organizations are getting shut out of high school gyms, and most of them are so starved for places to play that they'll pay a premium. If you use a fee-for-service approach for basketball and volleyball, you can do really well."

Haas has seen proof that an ineffective pricing structure can sink a gym; The Hoop - Salem was "as busy as it could possibly be," he says, but the margins were small and people there were used to paying very little for gym time. "It was always full, but they just didn't get the right dollars-per-court-hour that they needed. Just because you're busy doesn't mean you're making money. You have to be the right kind of busy."

With that in mind, The Hoop - Beaverton places an emphasis on programs that can increase the number of players on the courts, such as skill-development classes where the dollars-per-court-hour is higher than court rentals. "When you can get 20 to 30 kids on a court, your margins are much greater," Haas says. Like American Sports Centers, Haas stays away from single memberships, preferring to book organizations and tournament promoters that can take care of their own marketing and operations, in effect lowering The Hoop's labor costs.

Basketball remains the focus because volleyball margins are too low, but The Hoop is diversifying, adding wrestling tournaments and a large gymnastics event (the gymnastics organization brings all its own equipment), as well as non-sports events such as middle school dances. "We do multiple things, and that's why we're afloat at this moment," Haas says. "There are a lot of little things that we can do that will really increase our revenue streams. I think we're on the right track."

To the list of requirements for private gyms to succeed, one could also add a favorable lease arrangement and a suburban location that offers an endless supply of kids. Those and one more: A certain amount of hustling, even for mega-gyms like American Sports Centers. Though he calls the daytime memberships "gravy," Gallup notes, "We can't just sit back with our feet on the desk." As befits the SoCal location, American Sports Centers is starting Futsal leagues, as well as adult and senior volleyball leagues during down times. "We're not chasing anybody away," he says.

"Hustling to fill the place isn't the problem," insists Haas. "The demand is out there -- it's huge. The dilemma is that you have to sell memberships to fill the time between your bigger events, but as you add more programs that have higher margins you begin to push out your members, and then they get upset and leave.

"You have to have all these different pieces in place, and you have to have a solid business plan that isn't just membership-based. I tell people who call me right off the bat: If all you have is memberships, you're going to fail."