You can choose to leave the details to your architect or contractor, but ultimately it pays to know the composition of - and how to maintain - what's over your head.

"Oftentimes, owners spend large amounts of money on finishes, the things they see every day, but the roof is out of sight, out of mind," says Rick Cook, an owner of roof consultant ADC Engineering Inc. of Hanahan, S.C. "Owners may spend more on wall finishes and carpeting than they do on their roof, but if you don't keep the water out of your building it's going to ruin your wall finishes and carpeting."

Cook has heard it said by more cynical end users that there are two types of roofs: The ones that leak and the ones that are going to leak. More accurately, roofs can be categorized as either water shedding (steep-sloped roofs) or waterproof (low-sloped roofs), so-called even though no roof is leak-proof. Water-shedding roofs, clad in higher-grade finishes such as shingles of various materials, metal panels or tiles, dry quickly as water and snowmelt run off, and so require less in the way of construction materials. As Cook notes, a quick trip into the attic underneath most steep-sloped residential rooftops will reveal pinholes that let light in but keep rain out. "It doesn't leak because the water doesn't stay around long enough to leak through," Cook says.

Waterproof roofs, on the other hand, are only slightly sloped, lengthening the time it takes water to make its way from the roof surface to storm-water drains. (Most building codes require that water drain off completely within 48 hours, since no roofs are designed to actually hold water.) What makes them worthy of their name are the impervious materials used to construct them - either multiple layers of felt and modified bitumen slathered with either coal tar or asphalt ("built-up" roofs), or single plies of rubber, PVC or thermoplastic ("membrane" roofs).

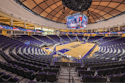

Naturally, there are roofs that don't quite fit into either classification. For example, many metal roofs (standing-seam construction consisting of zinc, copper or painted steel) are categorized as low-sloped but really fall somewhere in between: shallow-sloped, perhaps. A curved roof, to cite another example, could be categorized as sloping even if the geometry isn't completely accurate. In addition, since most recreation and athletic facilities have extraordinarily large footprints (they're typically the largest building on any college campus), architects will attempt to disguise their size by varying the rooflines and materials over the various program areas.

The region of the country matters, too. Warmer, southern regions are home to more low-slope roofs, both for economic and aesthetic reasons; the sunbelt also remains the last bastion of the built-up roof, which has ebbed in popularity elsewhere because of concerns about the environmental impact of their tar or asphalt emissions and a dearth of skilled installers.

Buildings in the North, by contrast, more often feature farmhouse slate or metal roofs or barn-like gambrel roofs. Steeply pitched roofs were traditionally dictated, of course, by the need to shed snow quickly. However, designers of public buildings are now a little more wary of roofs that might dump their wintry mix on the large number of passersby expected there. "It's not just the classic cartoon of someone being buried in a pile of fluffy snow," says Jim De La Plaine, director of operations for Houston roof consultant French Engineering Inc. "We're talking about ice heavy enough to seriously injure someone."

Architects working in wintry climes have a number of techniques at their disposal to deal with the problem. At ground level, they can locate walkways, landscaping and parking lots far enough away from roofs to ensure people, cars and fragile vegetation aren't within the fall zone. On roofs, particularly those clad in slippery metal, snow guards are now a standard feature, their horizontal profile preventing ice and snow from sliding off in large quantities.

"In our climate, it gets to be an issue," says Philip Laird, a principal with ARC/Architectural Resources Cambridge Inc. "I can think of an athletic facility here in Boston where street lights, cars and other things have been hit by ice chunks during a number of storms. We have sometimes designed flat roofs at the bottom of pitched roofs to catch snow and protect pedestrians."

Metal roofs do have numerous advantages, as well, from the range of colors available to their longer life spans (from 50 years for steel to 75 or more for copper, as compared to 20 to 25 years for membranes). Indeed, each type of roof has its distinct advantages; among low-slope roofs, for example, single-ply membranes offer many color options but are not as easily repaired as built-up roofs.

As with many other building components, end users will have to make a determination with their architect about the relative importance of up-front versus replacement cost. While prices vary regionally based on availability, Laird estimates the installation cost of standing-seam metal roofs as roughly three times the installation cost of single-ply membranes. The added cost can pay off, he says, both in the long run and in the event of a single case of inclement weather. "I'm working on a 30-year-old building with a low-slope roof destroyed in a hailstorm, which was followed by six inches of rain," Laird says. "It ruined 23,000 square feet of wood floor in the gym. Had that been a sloping metal roof, the hail would have dented it, but the owner wouldn't have lost $350,000 worth of wood flooring."

"Warranties do not protect owners. That's a fact," he says. "They limit the liability of the manufacturer. There are more exclusions in warranties than you can shake a stick at. To give an example, one of the very common exclusions is that the warranty will be void if wind speed exceeds gale force. That's 39 to 72 miles per hour - that's not that much."

"Most roof warranties have very limited value," agrees De La Plaine. "I think people believe all roof warranties are the same, and they're not. In addition to that, they normally state that the warranty doesn't apply until the building actually leaks. It's something you have to be very careful about."

Difficulties ferreting out warranty issues, dealing with contractors (who, Cook charges, "always seem to finish up jobs at 3 o'clock on Friday") and determining the best roof type and adhering method for the local climate are just a few of the issues that lead many recreation facility architects to work with roofing consultants. "We use a roofing consultant on all projects," says Tom Betti, a partner with Ankeny Kell Architects of St. Paul, Minn. "We work with a consultant who has experience across the nation, so we lean on him to help us spec the appropriate materials for different climates and conditions from Pennsylvania to Montana to Arizona." After all, Betti adds, "One of the biggest causes of litigation is a leaky roof, so hiring a consultant is really cheap insurance for us and our clients."

Roof consultants themselves say the cheapest insurance for building owners is performing regular roof maintenance, from providing pavers for HVAC maintenance workers to walk on to making sure drains stay free of debris. Most warranties, in fact, "will usually address all care items and spell out a reasonably fair presentation of what the manufacturer expects the owner to do," says De La Plaine. "Sometimes they require periodic inspections in order to maintain the warranty, just in case there's something going on."

"Just walking your roof twice a year is huge," says Cook. "Common sense would tell you that you should walk it at the end of summer and winter, your two extremes, and after any significant event such as high winds, extreme cold, whatever. A lot of times, leaks don't show up inside your building for a while. If a piece of metal coping blows off in a storm, six months later you could have rot and mold coming down a wall because nobody walked the roof and found the section missing and tacked it back into place."

Some years ago, Cook was up on the roof of the Savannah (Ga.) Civic Center performing an inspection when he took a call on his cell phone from a man who had just found a bullet hole in the roof of his building. Cook shared the man's perplexity at his discovery; he'd seen plenty of arrows, darts, welding rods and other detritus on roofs in his day, but never bullets or bullet holes. However, Cook was even more surprised after he ended the call and completed his inspection of the civic center - by the time he was finished, he'd pocketed seven bullets.

"It was just a coincidence that this guy would call while I was doing this inspection," says Cook, "but since then I've found bullet holes on a lot of roofs. There's a lot of square footage up there, and a lot of things can happen."

Certainly, there are aspects of sustainable design that were already widely practiced before the notion of LEED accreditation of entire buildings began to take hold. For example, architects have for years brought daylighting deeper into facilities such as gyms and natatoriums, although more for aesthetic reasons than for the possibility of energy savings (not that saving energy wasn't a consideration). Advances in skylights have helped this process along, and building owners are no longer as hesitant to introduce such components, formerly feared for their leakage potential, to their roofs.

Most noticeable among the changes to roofing in the sustainable-design era is its color. "Somebody told me that if you took every building in Manhattan and either put a white membrane roof on the flat part or put grass or sod on all the roofs, the temperature in the city would go down 10 degrees in the summer," Laird says. "If you use white or light-reflective roof membranes instead of the black or dark gray that were the industry standard 10 years ago, you reduce cooling loads on your building and on surrounding buildings, and you help lower the ambient temperature of the immediate environment."

Recognizing that bubbling pots of tar and highly emissive black surfaces were beginning to be considered relics of an unenlightened age, the Roof Coating Manufacturers Association in 2005 formed the White Coatings Council to "assist in establishing clear criteria" for the manufacture and use of such surfaces. Cook, who authored a 2005 industry position paper on the subject of LEED, thinks the focus on reflectivity is a bit one-sided, noting that in some cooler regions emissivity is beneficial in reducing a building's heating load. Cook's position paper took pains to declare the industry's unwillingness to be a "guinea pig" for unproven technology, and its desire to maintain a balance between environmental goals and everything else that roofs are supposed to accomplish. To that he adds, "The other thing about reflectivity is that white roofs don't stay white, they turn gray." Since studies on roof reflectivity are "based on a white piece of paper," Cook suggests that their accuracy isn't assured.

The architectural community, though, has embraced the concept, since specifying a lighter shaded membrane is as effective in gaining a LEED point as laying sod up there. End users, meanwhile, may be slow to take notice - if they ever do.

"Most people have no idea whether they have a rubber roof, a PVC roof, a built-up roof or a metal roof," concedes Laird. "They'll know they have slate if they can see it, but there are a lot of roofs you don't see. Nobody really cares what a roof is made of unless it doesn't work."