It doesn't matter whether Your basketball and football practice facilities are plain or pretty. Just make sure they're well organized.

Given the millions of dollars now being invested in athletic practice facilities at both the professional and collegiate levels, it's obvious that many people - coaches, athletic directors and franchise executives among them - still take practice very seriously. So important is practice to NFL teams that it has become common for them to spend more lavishly on their practice facilities - which often include player lounges and lockers, training rooms, exercise areas and other amenities - than on similar digs at their home stadiums.

"If you go to the St. Louis Rams' stadium, the locker room isn't at all impressive because it's empty six days of the week, even the week before a home game," says Kirk Warden, vice president of Clayco Inc.'s institutional business unit, which has designed and built practice facilities for the Rams, Atlanta Falcons and Baltimore Ravens. "The team just brings the gear, loads up the lockers right before the games and the players come. That's it."

Contrast that scene with the Ravens' opulent, $31 million headquarters and training facility, which opened in a Baltimore suburb in 2004. Amenities include a 10,000-square-foot weight room, a group cycling room, a half-court gymnasium, racquetball courts, a billiards room and expansive player lockers, each with plug-ins for music players and laptops.

Some of these amenities have even trickled down to college and university athletic programs, although within the parameters of much tighter budgets. If a school is to incorporate into its practice facility plush locker rooms and state-of-the-art training spaces, the trick is to do so without duplicating existing facilities.

Take, for example, the 2002 expansion to the University of Oklahoma's Lloyd Noble Center. The expansion juts out from the existing arena in an inverted "V" formed by two dedicated wings, one each for the men's and women's basketball programs. Although two full-court practice gyms account for much of the 60,000 square feet of new space, also included are comfortable player lounges and locker rooms that replaced dingy, cramped confines tucked within the Noble Center's basement. Oklahoma's basketball teams use their new locker rooms for both practices and games.

"These amenities are intended to help with recruiting, yet while cost doesn't matter with some programs, that wasn't necessarily the case at Oklahoma," says John Poston, a project designer with Ellerbe Becket Inc., which designed the expansion. "I don't want to call it restraint, but there was a budget and some discipline imposed on the process. The practice facility is very functional and of high quality, but nothing that we would consider over the top."

It would appear that the principle of function is the tie that binds the design of professional and collegiate athletic practice facilities. Whether such buildings are well appointed or more moderately adorned doesn't matter. Their ultimate success depends on whether the layout makes sense.

"It is a very complicated notion because you have a lot of different components that have to fit within the building, yet still be separate," says Warden. "We did the Rams' facility first, then the Falcons' and then the Ravens'. It's amazing how similar all three facilities are, if you distill them down to rudimentary bubble diagrams where you see intersections between player areas, coaches' areas, media areas, public areas, executive areas and support areas. Even though all three facilities are distinctly different, they still try to accomplish a lot of the same things."

Sure, money talks. But the level of attention given by a franchise to its practice facilities can speak to some players at even greater volumes. "Teams will sign big-name players, but it's the secondary level of players who really win Super Bowls," says Warden. "These guys are going to be paid reasonable salaries, yet when they get to work in an unbelievable place, that's what convinces them that, 'Hey, I'd rather be on an extraordinary team than anywhere else.'"

The most significant planning considerations don't always play out within the walls or even on the fields of practice facilities. "People might think it's better for players to be closer to the stadium, but most pro players don't live near the stadium they play in," says Warden. "Typically, we've found that there is an area that the players and coaches live in" - read exclusive suburban communities - "and it's more beneficial to build a practice facility that's convenient for them to make it to work and back."

Unfettered by the potential constraints of a tight downtown site, pro football practice complexes erected in the suburbs have the ability to sprawl across 32 acres, as does the Ravens facility in Owings Mills, Md. (Rams Park occupies 20 acres in Earth City, Mo., a half-hour drive from downtown St. Louis, and the Falcons' training facility and headquarters sits on 50 acres in Flowery Branch, Ga., 45 miles northeast of the heart of Atlanta.)

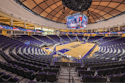

Such space is a luxury unavailable to most NBA teams, many of which in recent years have sought urban locales for their newly constructed arenas. Fortunately for NBA franchises, their practice facilities require far less room than their pro football counterparts. It has actually proven cost-effective for most pro basketball teams to house their training centers deep within their arenas.

The Mavericks' American Airlines Arena, for instance, rests on just 12 acres of prime downtown Dallas real estate. But within that space is a 19,200-seat arena, complete with all the trimmings, as well as fully equipped practice and locker facilities for the Mavs (the arena also houses locker areas for the NHL's Stars). The Mavericks' locker room and training center - which includes a full practice court, players' lounge and weight room - occupy merely 28,000 of the arena's 840,000 square feet.

As it happens, the design of these event-level facilities wasn't dictated by the demands of the seating bowl and concourses above. "It may seem weird, but everything kind of revolves around the loading docks because that's where everything comes in - even the players," says Dan Phillips, a senior designer at HKS Inc., which designed the arena. "They must come into the building through a secured area, which for the most part means the loading docks. And everybody wants to be there - the people who deliver goods or pick up trash, the TV production guys who want to bring their trucks into that location. So you do a lot of relationship drawings to determine highest to lowest priority, and you work from there."

Generally speaking, practice facilities rank fairly high in this process. But during the design of the University of Maryland's Comcast Center, which opened in 2002, an auxiliary gym was afforded greater precedence than perhaps most arena practice facilities - if only because of its multipurpose mandate. Not only does the 1,400-retractable-seat gym accommodate men's and women's basketball practice, it also serves as the competition venue for volleyball, gymnastics and wrestling.

"The functions in that gym affect everything else in the facility, so you have to put everything in there as efficiently as possible," says Pat Clancy, a senior project architect and project manager with Ellerbe Becket, which designed Comcast Center. (At Maryland, that meant locating three team locker rooms, an athletic training suite and the auxiliary gym all along the right-hand side of the same hallway. Together, these event-level components form the facility's east side.)

For many athletes, making the mental commitment to attend practice is already difficult enough. That's why designers of newer practice facilities endeavor to accommodate players by making the physical act as simple as possible. Before its 72,000-square-foot Football Operations Center opened adjacent to the existing Charles McClendon Practice Facility in August 2005, the Louisiana State University football team literally found itself shuttled each day from one place to the next on the school's athletic campus. "The problem was that the coaches were off the scene and the players were dressing at the stadium, which is a quarter-mile away. They were always getting bused over to practice," says Phillips. "Basically, we added on to the indoor practice field all the team's offices, meeting rooms and player facilities so they would have one place to go."

Likewise, Southern Methodist University is building a new basketball practice facility just to the north of the school's 50-year-old Moody Coliseum. The two-level, 42,000-square-foot Crum Basketball Center is connected to the coliseum via an underground tunnel so that, according to Phillips, "players can basically practice and dress in the new building and just walk to the field house for games."

Designers are often challenged by their clients to pursue building efficiencies to save money by suggesting that the two programs share certain spaces - training rooms, for example. Despite that logic, Phillips has found that at each institution various other issues factor into decisions concerning shared space. "We actually started down that road at SMU," he says. "But we realized that we were dealing with two head coaches who have two different views of things, so we tried to play down the middle. Eventually, the athletic director stepped in and said, 'Everybody gets the same thing. One program doesn't get any better facilities than the other.' We were able to get them to share the weight room and the training room, and use of those spaces is just going to be a scheduling issue for them."

At the Lloyd Noble Center, Oklahoma's basketball programs share a training room and a common space (with a hall of fame and second-level hospitality room) linking the practice facility to the arena - but that's where the unity ends. "Everything else was intended for each program to have a distinct identity to the point that they even have separate entries," says Ellerbe Becket's Poston. "The interior design of the office suites is completely different, too, based on the image each coach wanted to convey."

The three entries to the Baltimore Ravens training facility are similarly styled with dark cherry wood casework and doors, plush carpeting and custom artwork. Still, the significance of those three entries - one for the players and coaches, one for visitors to and employees of the executive offices, and another for members of the media - cannot be overemphasized. "In a pro football facility, the separation between public, private and media is critical," says Clayco's Warden. "You have to arrange the plan in such a way so that the media have access to at least certain areas of the facility. But you have to develop control points."

The same principle was applied at Maryland's Comcast Center. Because the auxiliary gym is used for summer youth camps, designers of that facility were instructed to incorporate additional control points to allow camp participants to directly access the auxiliary gym from adjacent parking areas and keep them from wandering beyond the gym and into private team areas.

On the contrary, one design goal for Brigham Young University's $23 million athletic complex - which debuted in 2003 and consists of two elements, an indoor practice facility and a student-athlete building - was to encourage student-athletes to interact with the general student body. When not occupied by the Cougars football team, the indoor practice facility accommodates some of the university's physical education classes. And across the street, students can socialize in the student-athlete building's first-floor Legacy Hall and sports grill/restaurant.

"There was a concerted effort to get student-athletes to mix with regular students," says Derek Payne, a partner with VCBO Architecture of Salt Lake City. "This central gathering area has really become a place for regular students to meet and talk with student-athletes, and the university likes that."

Local Customs Despite a university's best efforts to minimize the perceived gap between student-athletes and other students on campus, it's difficult for non-student-athletes to ignore the high-quality surroundings in which basketball and football stars train and hang out.

Nevertheless, much of the money and attention dedicated to practice facilities is aimed at helping student-athletes be better students and better athletes, and thus bring greater glory to their institutions. For instance, when outfitting basketball practice courts, schools usually take great pains to replicate the competition arena environment as much as possible. "They're laid out the same as the main arena court for the same feel," says Ellerbe Becket principal and project manager Steve Duethman. "They'll have the same logos and a fairly consistent scoreboard and speaker system."

Coaches have long used audio systems to simulate game conditions at practices by piping in artificial crowd noise. But while players warm up for practice, the atmosphere should be far less hostile. To that end, Oklahoma athletics officials thought it reasonable to retrofit the sound system controls in the Noble Center practice gyms to accommodate players' personal music players. "The idea there is to make it an environment the players want to spend time in, to give them control," says Poston. "They can bring their iPods, plug them in and go practice."

Some schools are now investing in accommodations for skill players. In addition to a full court, each of the men's and women's practice gyms at John Paul Jones Arena, which debuted last summer at the University of Virginia, is abutted by a smaller half-court designed especially for three-point shooting. The two courts, laid out in a T-shape configuration, are bisected by a ceiling-hung coaches' filming mezzanine. "We hadn't done that before," says Poston. "That was a little bit of an innovation for us."

VCBO also stepped into new territory with BYU's indoor practice facility. After the facility was designed to accommodate a 100-yard football field, the Cougars' former head coach asked for two shorter fields to be installed (a 75-yard field and a second, 65-yard field lie perpendicular to one another, forming a "T"). "The coach wanted to be able to have his offensive and defensive teams practice at the same time," says Payne, noting that the unique field configuration didn't change the overall building dimensions. "When you have a full field, the two teams bump up against each other. When you rotate the fields, there is less of a tendency for one squad to run into the other."

Other custom touches in the BYU indoor practice facility include translucent panels that ring the building where walls meet the ceiling structure. "Oftentimes, these places are a little dark. But by making the roof float a little bit, the facility doesn't feel so cavernous," says Payne. "Just because the team goes inside to practice, they shouldn't lose some of the characteristics of being outside."

One could debate whether off-the-field amenities such as laundry service and a mail drop - just two of many special features of the Baltimore Ravens training facility - actually help players perform better on the field. But Clayco's Warden is quick to point out that every element of training facilities - from practice fields and courts to lounge areas to weight rooms - is incorporated to support players' physical health and mental well-being. "They have to go to the practice facility every day of their lives, except for game days," he says. "Every day, the Ravens serve a breakfast and lunch to everyone who works in the facility. They serve dinner to the players, coaches and their families once a week. We've reached the point where the philosophy of creating a home away from home for the staff, players and coaches is finally catching on with every new facility."