On appeal, an arrested heckler finds his words shielded by the U.S. Constitution.

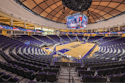

Jeffrey Swiecicki and several of his friends attended a 2001 Cleveland Indians baseball game at Jacobs Field. Jose Delgado, an off-duty police officer for the city of Cleveland, was working as a security guard and dressed in full uniform, including his badge and weapon.

Sometime during the game, Swiecicki and his friends were allegedly heard using loud and profane language directed at some of the players [see "Legal Action," Dec. 2006, p. 28]. Delgado, who was stationed at a tunnel near the bleachers where Swiecicki and his friends were seated, approached Swiecicki and asked him to halt his behavior or leave the stadium. When Swiecicki did not respond, Delgado moved toward Swiecicki, grabbed his arm and shirt to place him in the "escort position," and led him toward the exit. In the course of leaving the stadium, Delgado alleged, Swiecicki jerked his arm away to break from Delgado's grasp. (Swiecicki later denied any physical resistance.) At this point, Delgado wrestled Swiecicki to the ground, and told him that he was under arrest.

Swiecicki was charged with and convicted of disorderly conduct and resisting arrest (though his convictions were eventually overturned on appeal based on insufficient evidence). As a result of his arrest, Swiecicki sued Delgado and Jacobs Field in federal district court pursuant to 42 U.S.C. § 1983. Swiecicki argued that Delgado had violated his constitutional rights in three separate ways: By arresting him based on the content of his speech in violation of the First Amendment; without probable cause in violation of the Fourth Amendment; and through the use of excessive force in violation of the Fourth Amendment.

The Federal District Court for the Northern District of Ohio granted summary judgment in favor of Delgado, holding that qualified immunity (a federal doctrine that insulates government officials from liability when their actions have not violated clearly established law) acts as a complete bar to all of Swiecicki's federal claims. It was then up to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit to determine whether Delgado, when he escorted Swiecicki from the stadium, was acting as a private employee of the stadium or as a police officer for the city, and whether qualified immunity shielded him, as a law enforcement officer, from civil liability.

The answer to the first question is important, because the only way Swiecicki's federal claims could succeed would be if Delgado's actions were committed by a person acting under color of state law. Considering all of the relevant facts, the appeals court found that rather than calmly asking Swiecicki to leave the stadium, Delgado, while wearing his uniform and carrying a weapon, threatened Swiecicki and forcibly removed him from the bleachers. This evidence, combined with the fact that Delgado was hired by Jacobs Field to intervene "in cases requiring police action," suggests that his warning to Swiecicki amounted to a threat of arrest. In sum, this was more than a case in which a civilian employed by the Indians peaceably ejected an unruly fan from a baseball game. When considered together, the evidence indicates that Delgado was in essence a state actor during the entire time he removed Swiecicki from the bleachers, escorted him through the tunnel and arrested him.

Next, the appeals court employed a two-step analysis to determine whether a qualified-immunity defense applied. Considering the allegations in a light most favorable to the party injured, had a constitutional right been violated? Had that right been clearly established?

Regarding the first step in the analysis, Swiecicki claimed that his heckling was not so offensive as to give Delgado probable cause to believe that he was violating the disorderly conduct ordinance. In particular, he denied that he used profane language, and he further argued that the underlying message of his speech would have been protected by the First Amendment even if profane.

Even though Delgado did not have probable cause to arrest Swiecicki based on the content of his speech, the district court had held that "a reasonable police officer could have . . . believed that there was probable cause based on Swiecicki's loud and rowdy manner to support an arrest for aggravated disorderly conduct." Swiecicki, however, denied that his behavior was inappropriately loud or offensive. Since there clearly was a question over whether Swiecicki's conduct rose to the standard of disorderly conduct, the Sixth Circuit Court, taking the facts in the light most favorable to the plaintiff, held that Delgado did not have probable cause.

As for Swiecicki's claim that he did not resist arrest, the court held that Cleveland's resisting-arrest ordinance requires a lawful arrest on the underlying charge in order to sustain a conviction for resisting arrest. Since Swiecicki's convictions were overturned, the court held that Swiecicki's Fourth Amendment right to be free from arrest without probable cause was clearly established. The court therefore reversed the district court's grant of qualified immunity to Delgado on this Fourth Amendment claim.

The court also rejected Delgado's argument that Swiecicki's First Amendment protections did not apply in Jacobs Field, which he alleged is a private park. The court ruled that since Delgado had already been determined to be a state actor, Swiecicki's First Amendment protections applied. Once again, considering the facts in the light most favorable to Swiecicki, the court found that Swiecicki was heckling in a manner similar to other fans at the game. Because his heckling did not provoke lawless action, the First Amendment provided protection for Swiecicki's words.

Was Swiecicki's First Amendment protection clearly established at the time of the arrest? The court ruled that it was, since the content of Swiecicki's speech could not serve as the basis for a violation of Cleveland's disorderly conduct ordinance. The court therefore reversed the grant of qualified immunity awarded to Delgado.

While the court held that "for a baseball fan to make a 'federal case' out of being ejected from a game may well strike many as a colossal waste of judicial resources," the case does present some important issues to facility operators. First, it should be noted that the court's decision simply sent the case back to the district court for a trial. Therefore, Delgado may still win the case.

Even if he wins, however, the case should serve as a warning that just because a facility operator hires qualified police officers does not mean that the officers have total immunity in removing all fans. As Swiecicki demonstrates, the police need a valid reason for removing fans - one not based on their constitutionally protected speech.

Finally, while the court found that Delgado's conduct was a state action, thereby clearing the facility of any liability, facility operators will be held liable for the conduct of their own security staff. If Delgado had been deemed to be a private individual and he placed Swiecicki in an enclosed facility within the stadium, the facility operator may have been liable for the intentional torts of its employee.