Cincinnati Public Schools uses sustainable-design strategies to rethink the gymnasium.

Photo of a sensor-controlled gymnasium ceiling fan at Cincinnati's Midway School

Photo of a sensor-controlled gymnasium ceiling fan at Cincinnati's Midway School

You don't have to spend a lot of time searching the Internet to find study after study proclaiming the benefits of so-called green schools - facilities that create healthy, learning-conducive environments while saving energy, resources and money. Reports of improved test scores and reduced student absenteeism caused by illness come from all regions of the country. For example, at Third Creek Elementary School in Statesville, N.C. (the country's first LEED Gold-certified K-12 school, completed in 2002), test scores from before and after students moved into the building provide compelling evidence that learning improves in greener, healthier facilities. And an analysis of two school districts in Illinois found that student attendance rose by 5 percent after cost-effective indoor air quality improvements were made.

But can a similar parallel be made between green schools and increased performance on the basketball or volleyball court or in physical education classes? Ron Kull thinks so. "There would be no reason why you couldn't draw that same correlation," says the senior associate with GBBN Architects in Cincinnati, who is heavily involved with Cincinnati Public Schools' $1 billion facilities master plan. By 2013, CPS will be home to 54 first-class new or renovated schools - almost half of them LEED Silver-certified or higher. "If you're talking about how a student performs in certain environments, why wouldn't it apply to athletic facilities just as much as it does to classrooms?"

Seven years into the district's master plan, Cincinnati is fast becoming the site of one of the largest concentrations of sustainably designed schools in the country. Some of the green strategies include the addition of daylighting and stormwater management systems, geothermal energy technologies, low-flow plumbing fixtures, and low-VOC furniture, paints, carpets and adhesives. Increased recycling and composting efforts, reduced idling of school buses on school property, and improved overall air quality also are part of the plan. At the district's Pleasant Ridge Montessori School, which opened last August and is among the first building projects to be completed, an air-delivery system forces air to rise from the floor and through the ceiling, where it is filtered before re-entering the ventilation system with fresh outdoor air.

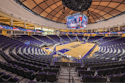

Gymnasiums also are a key part of the CPS master plan. Many elementary and secondary school gyms will feature heat-reducing roofs, ample daylighting from glare-reducing windows, high-output fluorescent lights and energy-efficient ceiling fans. Sensors will control the lights and fans to save energy, while also making the spaces more comfortable and conducive to extended periods of activity.

The ultimate goal, according to Robert Knight, GBBN's sustainable design initiative coordinator, is to marry energy efficiency with healthier indoor conditions. "The human body, just like the human mind, performs best in certain environments," he says. "At the professional level, the collegiate level and the high school level, people are looking for ways to create a competitive athletic advantage, and you do that through better indoor environments."

"The community has pushed us to be more aggressive with LEED," says Michael Burson, director of planning and construction for CPS, which enrolls 33,000 students (including more than 10,000 at 16 high schools). Almost half of the money used to fund the master plan is coming from a $480 million school construction bond approved by city voters in 2003. The Ohio School Facilities Commission, the agency charged with overseeing a statewide campaign to help districts fund, plan, design, and build or renovate schools, is kicking in another 23 percent, with the rest of the dollars coming from other local and state sources.

In April, CPS also was awarded an $80,000 state grant to significantly expand its urban timber program - a partnership between the school district, the Cincinnati Park Board and the Hamilton County Solid Waste District. The funding will allow CPS administrators to use recycled wood waste from trees cut down by the city in schools' furniture and shelving. Approximately 4,400 board feet of lumber has been milled and recycled so far, the district says. The majority of that wood comes from ash trees infested with emerald ash borer beetles, but oak and maple also are abundant. "What else could we do with that wood?" Burson asks. "It can be used in any gymnasium, for a floor or for bleachers."

"This is an ideal solution for the use of urban wood waste," Dave Gamstetter, the Cincinnati Park Board's supervisor of urban forestry, said at the time the partnership was announced. "Using this local resource in construction also aids CPS with their LEED certification process."

While it may be too early to determine exactly how these sustainable design strategies will impact building operations and maintenance, Burson already is figuring out how to train his employees to deal with the changes. "We have to concentrate on educating the staff, because the advances in the new buildings will be unlike anything they have now," he says, recognizing that the learning curve might be longer for adults than it is for young people.

Students at Pleasant Ridge Montessori School who helped develop and implement that facility's sustainable design program recently hosted public tours of the building, showing off and explaining all of the improvements. Burson notes the significance of students giving those tours. "The important thing for us, as a school district, is that we are training the city's youth to not become complacent about this and to get sustainability built into the culture," he says.

"You can't get away from sustainable design - although there are a lot of old-school people who are wondering what the value of it is. You have to spend money to save money, and that's a message that some older individuals can't understand," Kull says, referring in part to athletic directors who may think that implementation and oversight of green strategies are best left to district administrators. "But once they do understand, people recognize the need to think creatively about saving money, and then they realize the educational opportunities that come with it."

"Ideally, the athletic director is connecting the dots," Knight adds. "If you put these things in motion, you can call them green, you can call them sustainable design, and you can get a few LEED points - but you also can make your facilities the best they can be for their occupants."