Most facility owners who base their business models on basketball end up scrambling to diversify their program offerings.

WORKING CAPITAL Capital Sports Complex in District Heights, Md., supplements basketball with fitness, boxing and

WORKING CAPITAL Capital Sports Complex in District Heights, Md., supplements basketball with fitness, boxing andThe 90s were heady days for the sport of basketball. While baseball had its Babe Ruth in the pre-sports-marketing era, the NBA was able to leverage its Babe Ruth into a global phenomenon, from the pros down to youth leagues. The economy was booming, and many entrepreneurs were poised to cash in on Americans' hoop dreams.

Those whose basketball-centered facilities have survived - whether they're succeeding in or struggling through the second recession of the post-Michael Jordan era - say that while basketball is a major draw and a solid contributor to their revenue stream, it might be starting to lose a bit of its bounce. After more than 20 years atop the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association's annual participation survey, basketball remains by far the country's most popular team sport, but in a recessionary period in which all team sports are taking a participation hit, the gap between basketball and soccer is narrowing. Also, no owner of an indoor sports mecca has ever found a way to combat good weather - there are simply times when most athletes will choose blacktop over hardwood.

250+ Exhibitors & 190 Educational Sessions | abshow.com.

And so, even in a facility bankrolled by and bearing the name of a popular former pro, there's a lot going on besides hoops. "We're 35 percent basketball and other court sports, 35 percent roller hockey and 30 percent entertainment events," says Brian Siegel, a partner in Detroit's Joe Dumars Fieldhouse. "Detroit hasn't been the poster child for recovery, but we're fighting our way through it. Different things we diversified into have helped us weather the storm. For example, we learned the restaurant and bar business, and while we don't know if it's good planning, good management or just luck, we've been able to succeed at it, which is unusual in athletic facilities. We've become a business with a lot of moving parts."

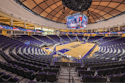

Photo of a basketball court at Capital Sports Complex

Photo of a basketball court at Capital Sports ComplexFourteen years ago, K.C. Currin, then the head of sales and marketing at Atlanta's Run N Shoot, told Athletic Business of the ownership's dreams of franchising its low-fee, pickup basketball model to a number of other cities. "This can work anywhere," Currin said, "and in a place up north where it's cold most of the time, they could double our numbers."

But the success of the Atlanta facility, housed in a shuttered big-box store, proved hard to replicate elsewhere. Only one other Run N Shoot opened, in District Heights, Md., just inside the Beltway east of Washington, D.C. Debuting in 1998 as the same type of 24-hour, no-long-term-membership facility and located in a former Caldor department store, Run N Shoot closed suddenly in 2005 after a period of apparently severe financial difficulty.

Jumping into the void was Rodney Hunt, whose McLean, Va.-based RS Information Systems, a government contractor, is one of the region's largest black-owned businesses. Working with the building's jilted landlord, Hunt in 2006 reopened the 113,000-square-foot, 10-court facility as the Capital Sports Complex - and inherited many of the same troubles, according to his brother, Kevin, who was recruited from Texas to manage the facility.

"The business model originally was that we were going to provide court time to teams and tournaments on a day-to day, week-to-week, month-to-month basis," Kevin Hunt says. "In this economy, it's a terrible business model. Once I started reviewing the numbers, it was clear we needed to diversify quite a bit."

Photo of stationary bicycles at Capital Sports Complex

Photo of stationary bicycles at Capital Sports ComplexTo that end, Hunt has been working to remake the interior that his brother spent nearly $1 million refurbishing. The original department store had a food-service area, which Hunt has just leased to Everlasting Life, a health food restaurant that will add a childcare area and utilize the currently underused spa area. The smaller of the facility's two aerobics rooms has been leased to a company called Old School Boxing, which will run various boxing programs and help sponsor regular amateur fight nights. A computer learning/training area (the cost of which Hunt had hoped would be defrayed by nonprofit funding) sits in front of a space now containing a new, leased recording studio. The facility's sales manager is working on a plan to bring in boardless indoor soccer for kids' clinics and play. The fitness center, which includes a VIP training area touted as a favorite of some local professional athletes, will soon host regular events through an agreement with the RAW Powerlifting Federation.

"When you have a facility that's as big as ours, with lots of dead space in it that you have to air condition, heat and light all the time, you either have to fill that space or take that loss," Hunt says. "The dynamic of the company had to change; certainly the business model had to change. And now we have some residual income coming in from something other than the basics."

Steve Suttich's business model is slightly different, but basketball is still king at his Beaverton, Ore., sports center. Suttich calls it a multiactivity facility on the strength of the dodgeball games, corporate meetings and quinceañera celebrations held there, but The Courts got its name for a reason - the 30,000-square-foot former warehouse contains 28,000 square feet of hardwood, comprising two regulation high school basketball courts, two smaller basketball courts and two full-size volleyball courts.

Photo of a weight room at Capital Sports Complex

Photo of a weight room at Capital Sports ComplexHis facility's success, he says, is due to the decision to leave administrative tasks to its customers. Like the well-known and regarded American Sports Centers down the coast in Anaheim, Calif., The Courts relies on relationships with adult or youth sports programs such as Portlandbasketball.com to rent out its space without necessitating any administrative effort on the part of Suttich or his staff. "Our concept is we put the facility together, and we have long-term contracts with all sorts of different groups, primarily those that run basketball leagues, camps and clinics," Suttich says. "We hope they make money, and we make money off being a sports landlord. We've been profitable every year we've been open."

Suttich has seen much to suggest that this is the best business model for indoor sports. In the mid-1990s, Suttich was one of three developers who presented the concept of indoor family sports centers in abandoned big-box stores to what was then called Price Costco, and the Costco SportsNation division, for which he served as general manager, subsequently built one test facility in Tualatin, Ore. After nearly five years, Costco pulled the plug on the idea, and the huge facility was sold to California-based Leisure Sports and converted to a more conventional, fitness-focused ClubSport facility.

"Having experienced SportsNation from the beginning to virtually the end, in my opinion it's got to be a simpler equation than trying to run the whole business," Suttich says. "There are too many elements to it. The bottom line is it's such a seasonal business, and the overhead is just too high. You have to have all these things going on, and staff and administer everything. I say to people, 'been there, done that, don't want to do that anymore.' I'll let the young people deal with those headaches."

Photo of a workout room at Capital Sports Complex

Photo of a workout room at Capital Sports ComplexIn Suttich's region, few of the basketball facilities that opened at the crest of the 90s wave survive in their original form. For example, The Hoop, the northwest's answer to Run N Shoot, opened facilities in Beaverton, Vancouver, Wash., and Salem, Ore.; the latter is still around, while the Vancouver Hoop was sold to a Russian Orthodox church and became a school, and Beaverton's is now a Y.

As many such facilities succeed as fail; in fact, Suttich reports that SportsNation managed about an 11 percent return on investment, but that was below the 15 percent that Costco was making on a typical wholesale-goods warehouse. "SportsNation was a rental facility, but the primary business was club memberships," Suttich says. "The activities we did for outside groups, the tournaments and leagues, augmented revenue for the membership base. That's what kept our prices fairly low in the quote 'fitness industry.' We were comparatively low because we had that additional source of revenue, which was players."

For Kevin Hunt, it's all about finding additional sources of revenue. "We do AAU tournaments, every year we have the women's junior national tournament, and we're doing several other big tournaments. In the boxing area we'll have fight night, and in the fitness center we'll have powerlifting." Hunt pauses, and laughs. "And any other idea we can come up with."

Basketball, he's finding, is a tough market by itself. The gym's per-player fees have remained low - $12 a day, $25 a week, $65 a month and $155 for three months - but the clientele seems particularly price-sensitive. This gibes with Suttich's experience out west. "When The Hoop first opened up in Beaverton back in 1995, we had lunch with the owners one day, and they said they wanted to do nothing but basketball. They wanted to get all the high-end basketball players," Suttich says. "We said, 'Have at it.' The Hoop went out of business because there weren't enough high-end basketball players that wanted to pay what it cost to have what we used to jokingly call a country club for basketball players."

A SPIKE IN POPULARITYThe Courts in Beaverton, Ore., owes its success to its relationships with the adult and youth sports programs that rent court time.

A SPIKE IN POPULARITYThe Courts in Beaverton, Ore., owes its success to its relationships with the adult and youth sports programs that rent court time.And the lower-end players, Hunt says, won't stand for an increase of even $2. "You can't charge them enough to pay your overhead, and in the process you're just going to push people away," he says. "I just don't think basketball facilities are able to sustain themselves just with basketball. At least, ours can't."

Who succeeds? It depends on the location. Pure basketball gyms in urban centers survive on volume, with many city dwellers starved for places to play. Suburban gyms parlay their large number of courts into tournament sites, running other programs around the needs of their anchor tenants. Leasing a building, no matter where you're located, is the only way to go.

"The cost of dirt is prohibitive," Suttich says. "Everybody who has tried to do it where they buy a lot and put a building up on it has not really been able to make the numbers work because the parking lot has to be so big. We're able to make it work because we're in a business park, with 1,000 employees who use this facility Monday to Friday from 6 a.m. to 4 p.m. Every weekend we have a tournament where, if we need 400 parking spots, we have them. If we had to buy this building and the parking lot, we wouldn't be profitable."

Hunt at least has that part of the equation figured. The rest, he admits, he's learning as he goes. However, in spite of the rough beginning and an economy that he says has "devastated" local families' disposable income, Hunt is optimistic that with more diverse program offerings, Capital Sports Complex will soon justify his and his brother's faith.

"We haven't broken even yet, but by the first of the year I'm hoping to be in the black and at least showing a five percent profit, and then move forward from there," Hunt says. "Per capita income is about 30 percent lower where we are than in the surrounding area; if I could move this business from District Heights, I think the dynamic would change. But we are where we are, and have to make it work with what we've got."