![The Pavillion [Photo by Alan Brandt]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2021/10/1268BPRDPavilion6.61794f681c2c4.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&q=70&w=400)

In Ottawa, Ont., the Rideau Canal is lowered and flooded during the winter so that a surface suitable for recreational ice skating is allowed to freeze naturally. “If you ask someone — ‘What’s an amazing skating experience?’ — being out on the canal in the evening with the lights twinkling and your flask of bourbon in your pocket, it’s pretty well an amazing winter experience,” says Viktors Jaunkalns, a founding partner of Toronoto-based architecture firm MJMA.

But even Canadian winters are being shortened by climate change, and in some parts of certain provinces the process of municipalities flooding outdoor rinks is becoming a thing of the past. “The climate in the past 50 years is different in the wintertime, and it used to be that you could naturally flood an area, and the city schoolboard here did that for a long time. Just hammer some 6-by-6s into the fields, put some boards around and flood it, and you could count on that to be an ice surface for a bunch of months,” Jaunkalns says. “That cannot happen anymore.”

Now, it may take a cold snap, some city-supplied hoses and a host of neighborhood volunteers to create outdoor ice — a scenario that unfolded not too long ago in Toronto. “It was just remarkable,” Jaunkalns recalls. “Then the temperature elevated, the rains came, the ice disappeared and all of that fantastic spontaneous community activity went away. But when it was there, it was absolutely lovely.”

Given the wistfulness with which Jaulkans speaks of the outdoor recreational skating scene in Canada, it’s little wonder that MJMA is behind some of the most inspired indoor ice facility designs in all of North America.

According to Jaunkalns, who helped launch the firm in 1988, lots of indoor ice arenas popped up in all parts of Canada around the time the country was celebrating its centennial in 1967. These facilities featured a primitive envelope around a single rink served by a mechanical ice plant. Most have reached the end of their functional life and are now being replaced by more diverse civic recreation destinations in which ice is just one component.

“I think we always get a lot of support when we say we’d like these projects to really be centered on the social heart, so it can be a kind of communal collector between athletes in an ice rink, families in a library or people exercising in a swimming pool,” he says. “And then there’s this sort of social center. I think if there’s one thing that’s important, it’s that. And that lets it be recognizable as a real communal building and not just a place to transit through. It’s really a place that you could say, ‘I’d like to go and hang out there.’ ”

Back to the drawing board

Emphasis on social consciousness is reflected in a desire to combat the very forces that are changing the skating landscape. It’s been on the mind of MJMA designers for a good 20 years or more, but total carbon neutrality is a relatively recent goal embraced by prospective ice arena clients, as well. Says Jaunkalns, “Two city councils have evaluated their stance on how to mitigate the problems of climate change, and they have come back to say, ‘Our decision now is that we’re going to eliminate greenhouse-gas-producing equipment and be net-zero carbon.’ And we’ve been instructed to take the projects back to the drawing board and retool them for a totally electrified future. We are working on those project types now.”

And of projects already online, Jaunkalns says, “I think we’ll be going back to study a lot of these. The problem is a lot of them still have gas-powered things in them. They have gas-powered boilers and air-handling units. Our big switch now is really the total electrification of these systems and the elimination of greenhouse-gas-producing equipment. Not impossible, but some of those facilities likely won’t be retrofitted. I think it’s fair to say moving forward the majority of new facilities will have to be really trying to meet these advanced targets.”

That means building infrastructure to accommodate the charging of electric ice resurfacers and paying more attention to the building envelope and its low-E ceilings; non-glare, highly insulated glazing; geothermal heating potential and photovoltaic opportunities. That is, if there’s an envelope at all. Mechanically frozen open-air ice facilities are now extending the skating season in both Canada and the United States.

“There is a kind of configuration around here that the parks and recreation department had of a rink and then a type of recreational loop or area adjacent to it that would be fed off the same refrigeration system. That’s where all the kids are learning to skate, and it’s super popular,” Jaunkalns says. “In fact, we were working on a project just north of the city here where a developer in a community was proposing an open-air facility, and we proposed a type of open-air market where the ice surface dimensionally made sure that you really couldn’t play hockey on it. It’s an abstract form, but you could skate on it, and in the summer you can rollerblade or have a concert or a market. Instead of having the central space be the rink, it was more of a public plaza, and that was really well-received by the municipality, because really that ice surface is there externally for maybe three months. During the shoulder seasons and the summer, there’s all sorts of great community things that could happen with it. I think that’s a project type that we’ll be seeing more of.”

Under one roof

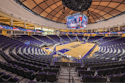

Another model that has caught Jaunkalns’ attention is the roofed skating pavilion, including one designed by Portland, Ore.-based Opsis Architecture. The Pavilion, located 160 miles to the southeast in Bend, is a roofed rink screened from the elements on two sides by ETFE panels and served by an indoor ice plant and community room. “If anyone is building outdoors, they would certainly consider something more like the Bend Pavilion, where the rain and solar effect on the ice is taken away, but you can still have something that’s outdoors,” Jaunkalns says. “You really get great protection for really not a massive investment.”

Opsis partner Jim Kalvelage crunches the numbers. “An enclosed facility might be about $16 million, and The Pavilion was about $11 million,” says Kalvelege of the facility that opened in December 2015. “Operationally, an enclosed facility might see about 70 percent cost recovery, and The Pavilion is 100 to 110 — so you can actually make money. At least Bend has, so far.”

A number of factors made a covered rink the natural choice for Bend, a community that Kalvelage describes as an outdoor recreation mecca. “Bend’s climate is now becoming Portland’s climate. Things are moving around,” he says. “Bend draws people from all over. In the summer, spring and fall, people want to be outside biking and hiking and kayaking. River rafting. There’s so much to do. The idea of having an indoor facility didn’t really make sense. But they realized, too, that part of that outdoor recreation is skiing and snowboarding and cross-country skiing, but what about hockey and just ice skating?”

Though it’s used for ice sports roughly five months out of the year, Kalvelage estimates that half of the Pavilion’s 75,000 annual visitors are drop-in skaters. “It’s so much nicer than being indoors,” he says. “You’ve got great lighting, you’ve got wind protection, you’ve got solar protection on the ice. It really creates the ideal environment from an experiential standpoint, and it harkens back to where hockey started — outdoors.”

During the other seven months of the year, The Pavilion’s ice is replaced by a sport court and used for basketball, volleyball, futsol and other activities. Ramps and mini-halfpipes accommodate skateboarders. “During the summer their big deal is the summer youth camps. It’s probably an eighth of their income,” Kalvelage says. “But they also get adult leagues playing and adults just recreating. There’s also a parklike environment next to it with fire pits and a picnic pavilion, so people can rent that out, too. You can have company parties and events. They really gave a lot of thought to it, and it’s pretty active in the summer, as well.”

When asked if its open-air nature could even help pandemic-weary patrons overcome their participation hesitancy, Kalvelage responds, “Absolutely, 100 percent correct. You’re still outdoors, so your chance of attracting people is going to be a lot better.”

Both he and Jaunkalns agree that more municipalities may be attracted to the structure type moving forward. “It’s all there,” Kavelage says. “Financial sustainability. Building more with less. You’re using less materials, less energy. Healthier environment. It’s really a great resource. I suspect at some point there will be more of these being built. There has been interest from Colorado to Washington, places that share similar climates and also that outdoor recreational consciousness. That’s why they have interest in a pavilion-type structure.”

“That type of public pavilion that is at least rain- and sun-sheltered but is open to the elements and open to other uses in the summer, I think we’re seeing that’s really a growing typology,” adds Jaunkalns. “And it’s healthy too. It’s open-air, natural ventilation. It has a lot of benefits to it.”![[Photo by Shai Gil]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2021/10/16x9/1469_BMRC_Binder.61794eac186cb.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) [Photo by Shai Gil]

[Photo by Shai Gil]

Thinning ice

Jaunkalns sees evidence — even in Canada — of a seemingly steady deemphasis of ice hockey in recreation settings. He points to the MJMA-designed Bernie Morelli Recreation Centre in Hamilton, Ont., which features an outdoor ice surface designed as “again, an abstract form not intended for hockey, with islands in the middle that make it impossible for shooting a puck or organizing a game,” he says. “It’s really much more for casual and family skating.”

While the facility lacks any indoor ice component, the outdoor loop is maintained by mechanical refrigeration. “The climate change gods are against us everywhere, so it has a refrigeration system under it,” says Jaunkalns. “It’s a small one. It has a three-quarter-scale refrigeration system and a mini-Zamboni, so everything is scaled down — but hyper-popular for the community.”

And then there are cases of no ice at all. Jaunkalns estimates 60 to 70 percent of all MJMA recreation projects lack an ice component. The majority of those that do offer ice typically feature more than one sheet, but the winds may be changing. “We worked on a project in the northwest of the city here that was originally thought of as a four-pad arena,” he says. “Eventually, it became a four-pad indoor soccer facility that is convertible to ice, but they’ve never converted it. It’s always stayed soccer. Hockey is still popular, but down from its ruling position as the number-one sport. I think we’re seeing a cultural diversification of sport geographically all across the country.

“You see it in the Olympics, where they’ve got to keep up. We need skateboarding. We need BMX. We need snowboard cross. I think we see that diversification across the board. That doesn’t mean that we aren’t still doing ice facilities. It’s just saying that there’s an increase in a kind of a la carte selection of wellness and recreation activities. People have busy schedules, and they may have a more varied recreation program choice than just saying, ‘I signed up for hockey every Thursday at 8 o’clock, and I’m going to do this for months and months.’ ”

Jaunkalns was as shocked as anyone to see British Columbia hit 121 degrees Fahrenheit in early July. Still, he doesn’t think that climate change has necessarily driven more skaters indoors, resulting in greater demand for arena construction. “I think what it has done is taken out some of the fantastic and romantic ability to have a naturally flooded rink in your park where you can go for a skate at night,” he says. “It sort of has taken away that quite amazing feeling. It’s magical when it happens.”

In the meantime, designers will no doubt increasingly rely on alternative structures and mechanical refrigeration to create something close to magic.

![[Photos courtesy of The Chemours Company]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2021/10/16x9/sidebar_SAP_Center_Image_V2.61794ccfb1329.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400)