More architectural and marketing savvy is going into the design and renovation of spectator facilities, as architects and owners try to stave off obsolescence.

"I think obsolescence is going to happen less in the future than it has in the past," says Tom Waggoner, a principal with Kansas City, Mo.-based 360 Architecture. "The new buildings are well set up for adjustments to be made as the times change, even in a challenging time economically. All of us have tried to build more flexibility into these facilities, more so than in the past. Because a lot of square footage has been built into them, I think they're going to be able to weather the storm."

It was a perfect storm that engulfed facilities like Charlotte Coliseum and the $52.5 million Miami Arena. These were 100 percent publicly funded arenas, meant to showcase a variety of events, and built on the cusp of some major changes that their designers either failed to anticipate or were unable to accommodate within very tight budgets.

The first was a gradual shift then taking place in the way tickets to sporting events were packaged and sold. The 1970s and '80s saw facility owners focus increasingly on up-front money in the form of season tickets and leases on suites, rather than on less-certain game-day sales. A parallel change, also gradual, saw the sales emphasis (and the fans' expectations) shift from sports to entertainment, perhaps to justify the rising price of tickets. In a span of perhaps 10 years, the action down below seemed of less importance than the range of food-and-beverage options, the amount of leg room in the seating bowl and the activities occurring live and on myriad video screens whenever there was a break in the action.

"Professional and, increasingly, collegiate teams realized that because it is about entertainment, there are other ways to make money, with retail, hospitality, concessions and full-service restaurants," Waggoner says. "And so, spectator facilities over the past 20 years have been created to maximize those sources of revenue."

Along with this new economic model came updated guidelines for facility design that, alas, arrived a bit too late for facilities that opened in the 1980s. Building codes had tightened up considerably in the area of life safety and gender equity, necessitating wholesale alterations whenever renovations were planned - and then, in 1991, the Americans with Disabilities Act was passed, bringing a completely new view of everything, from egress to wayfinding to the seating bowl.

"The biggest change was ADA," says Brian Tennyson, a principal with LMN Architects in Seattle. "But in general, a lot of venues clearly no longer met the needs of the clientele, so there was a big push to upgrade."

Adds Waggoner, "The building codes took a while to catch up in terms of the number of toilets you need to have, and the greater number that you may need for women; health codes were made more explicit about what you need to safely prepare, sell and store food; and also, ADA made clearer what you need to do to be accessible to all. These created a lot of positive aspects to spectator facilities, and have helped set up the newer buildings to maintain their viability in the future."

But what of the older buildings? Arenas and stadiums that were built just for sport tend to feature small building footprints, narrow concourses and limited height, making it harder to add luxury suites and leaving little room for ancillary spaces such as restrooms and concessions stands, let alone retail outlets and clubs. Suburban facilities not constrained by neighboring structures or the street grid at least offer the possibility of adding usable space outside the building's original footprint. Jon Knight, design director at Populous™ (formerly HOK Sport), which is in the midst of modernizations of Kansas City's Kauffman and Arrowhead Stadiums, among others, says the firm focused most of its energy away from the game.

"If you look at those buildings and where people sit, they have great, contemporary sightlines that a brand-new building might have," Knight says. "We were able to, in essence, keep the seating bowls as they were, but add on to the buildings to create a 21st century experience."

Buildings that are "delineated tightly," Knight adds, offer little such opportunity. However, LMN Architects handled an upgrade of such a structure in the late 1990s, showing definitively that there are alternatives to demolition.

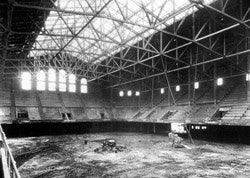

The renovation of the University of Washington's Bank of America Arena at Hec Edmundson Pavilion (top) saw the resurrection of the original arched windows (center) and the removal of a 1960s-era acoustical ceiling (bottom).

The University of Washington's Bank of America Arena at Hec Edmundson Pavilion was born in 1927 as the University of Washington Pavilion. The $600,000 field house, which was renamed the Clarence S. "Hec" Edmundson Pavilion in 1948 and was thereafter commonly referred to as Hec Ed, served as a horseshoe-shaped arena for basketball, volleyball, gymnastics and other events. Originally designed with removable flooring and seating (over dirt and two-by-fours) in the lower bowl, it was used as an indoor practice facility by numerous teams.

"Almost every sport used it at some point because it was just raw, covered space," Tennyson says. "So, the golf team was in there practicing, and pitchers would throw in there when it was raining. It had a track, as well. We dealt with probably 30 user groups when we first got involved with the building."

The university, which had performed a number of minor alterations to Hec Ed over the years, realized that the field house was "trying to do too many things," Tennyson says, and so a number of sports teams were moved out, thanks to a major capital campaign that funded several new athletic facilities.

Aesthetic improvements included the removal of an acoustical ceiling added in 1967 so that the space could be used for concerts, and the uncovering of six large arched windows that had been painted over to allow theatrical-performance blackouts.

Working within the historic brick structure was a major challenge, as was reaching the university's goal of 10,000 seats for basketball. "We just got there," Tennyson says. "We were really limited by the shell of the building." Even with those constraints, the designers had seating bowl options, with one plan that would have accommodated a capacity of 12,000, albeit putting three-quarters of the crowd on bench seats. (The university opted instead for higher-quality seating in much of the bowl.)

Tennyson says that what made the $35 million renovation possible was the fact that Hec Ed was built as a multipurpose space - it featured concourses much wider than those built for single-purpose arenas of that era, offering the designers more flexibility. To be sure, it also had more worth saving, aesthetically speaking, than the cookie-cutter spectator facilities of later eras. "We went through this process of uncovering historic components that in the original building were part of its identity but had gotten covered up by the various Band-Aid renovations," Tennyson says. "So it was not only a revitalization of the facility as a venue, but also a resurrection of its character."

Collegiate spectator facilities have an edge in this regard, as many such buildings enjoy a collective hold on alumni (that is, donors') consciousness. Buildings such as Duke University's 69-year-old Cameron Indoor Stadium - a primary template for the Hec Ed renovation, at the urging of then-UW basketball coach Bob Bender, a Duke alum - are far less likely to be abandoned than even revered professional stadia. But, these days, the viability of a collegiate building and that of a professional building are determined in a similar fashion, even if the economic models are different: It's all about the ancillary areas.

"Each campus is different, but adding practice courts and halls of fame to a collegiate spectator venue adds to the experience for recruits, and therefore protects against obsolescence," says Chris Lamberth, director of business development for 360 Architecture. "I really love what UW did with Hec Edmundson. Those stories are out there - it's not always the case that these buildings get blown up."

More typically, facility owners tweak their buildings to respond to market forces. The trouble at the moment is how to know what the market for professional and college sports will be like even six months from now.

"The economy is probably the next challenge for all of us on the design and ownership side," Waggoner says. "Are individuals and corporations going to invest in long-term leases for suites as they used to?"

To a certain extent, a change in the market has been perceptible for some time now, as the rush to build greater numbers of suites has given way to an opposite trend - suites in many buildings are being combined to create new seating options. This is particularly true in arenas, where corporate bigwigs or wealthy donors once demanded the exclusivity of a skybox, but now want both an exclusive space to wine and dine clients and seats close to the action. Other, less wealthy customers have demands of their own; smaller companies, for example, want a suite-like experience but don't necessarily want to deal with 16 seats of inventory at every game. These are the sort of forces that led to the situation at Milwaukee's Bradley Center, which opened in 1988 with 68 luxury suites but has gradually seen those consolidated - 10 were remade into Club Cambria, three into Club 71 and three into the Miller Lite Home Court Club - leaving 52 suites, 45 of which are under season leases and seven of which are available on an event-by-event basis.

Salt Lake City's EnergySolutions Arena, which debuted in 1991 as the Delta Center, has undergone a number of similar alterations to its original total of 56 suites. Its most recent renovation combined four suites to create the Executives Club, which offers many of the same perks as leasing a suite, including reserved parking, "in-suite attendants, concierge and in-seat service to cater to your every need" (as the facility's web site promises), a private will-call window at the box office, and so on. What's different is the food - a full-service in-suite VIP buffet dinner with soft drinks (alcoholic beverages are available for purchase) instead of catered food that must be specially ordered - and the commitment. Membership in the Executives Club requires a minimum lease of just four seats, not an entire suite.

Jim Lohse, a principal with FFKR Architecture of Salt Lake City, which designed the building and continues to work on its alterations, says it was easy for the architects to understand the viewpoint of suite-holders - their firm leased one at EnergySolutions Arena for a few years.

"Suites are hard to deal with," Lohse says. "There's the money issue, and you almost have to have somebody full-time managing it. You've got to rustle up 12 to 18 people for every game - many times you end up filling it with employees because you can't fill it with clients - and then you've got to order food. The Executives Club opens up the suite experience for small companies that can't afford $100,000-plus a year."

To accommodate the heaviest hitters, bunker suites have come to EnergySolutions Arena - lower-level clubs without a view of the bowl that are purely for entertaining when the game isn't being played, from which guests enjoy access to courtside seats when the action starts. The bunker suite concept is being added to many spectator facilities (both in new construction and during renovations) in a variety of ways. At Auburn University, an arena designed by 360 Architecture that will open in time for the 2010-11 basketball season will feature suites on the building exterior at ground level that will service both arena-goers and Auburn football tailgaters, since the arena is being built adjacent to Jordan-Hare Stadium. "We saw an opportunity that was maybe just for that market," says Waggoner. "In other places, it might not make sense at all."

A new, unique arrangement at Arrowhead is an outdoor suite that, save for the lack of a roof, looks a lot like traditional stadium suites. Knight, who says that one of the purposes of such alterations is to "give fans access to a part of the experience that they've never had before," believes that the biggest change to spectator facilities will continue to be more rhetorical than structural. "I'm not sure that these buildings will change dramatically, but what will change is the way they are sold to spectators," he says. "A lot of teams are figuring out how they can create different levels of expectations and experiences based on what a spectator's ticket package is. More and more, there are clubs that have less to do with opulence and more simply with fans paying a premium to be there, whatever 'there' is."

This, designers say, should help ensure that the current generation of spectator facilities reaches their full potential as public buildings and - with any luck - ripe old age.

"There are always going to be advancements, always going to be changes in the expectations that spectators and owners have of these buildings," says Knight. "The Museum of Modern Art was the standard for art museums in the United States, and yet it has now been completely transformed. We're always changing. We change the design of schools as ideas change about how kids should be educated. It's tough to conceive of a time when the purpose behind built architecture didn't change. It's a moving target."