Investment in facilities has made the Big Ten a player in the search for college baseball talent.

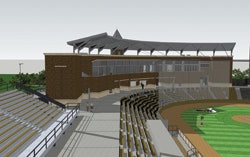

DOUBLE PLAY Thanks to a partnership with a professional baseball team, Penn State now boasts one of the most lavish on-campus baseball facilities in the North.

DOUBLE PLAY Thanks to a partnership with a professional baseball team, Penn State now boasts one of the most lavish on-campus baseball facilities in the North.As junior infielder Scott Wingo touched home plate in the bottom of the 11th inning on June 29, his University of South Carolina teammates stormed the field to celebrate not only the school's NCAA College World Series title, but its first men's national championship in any sport.

Despite that feat, the game story in the next day's sports pages focused more on the venue in which it was accomplished. The baseball game was the last ever played at Omaha's iconic Rosenblatt Stadium, the site of the CWS for each of the past 61 years. Also the former home of the minor league Omaha Royals, the stadium is expected to be demolished upon next year's opening of TD Ameritrade Park Omaha, a $130 million, 24,000-seat amenity-filled stadium with the capacity to expand to 35,000 seats.

Although it has been criticized by the more nostalgic fans of America's pastime, the move on behalf of the NCAA and the City of Omaha is nonetheless representative of the facilities arms race that's occurring throughout college baseball. "The evidence of change is in Omaha," longtime University of Minnesota baseball coach John Anderson says of Rosenblatt's replacement, which as of this writing was not expected to host a professional baseball tenant upon its opening. "I'm on the NCAA baseball committee and we're building a $130 million stadium for essentially two weeks worth of baseball."

Those winds of change have for years been blowing through the hotbeds of college baseball - the South and the West Coast - where universities have been competing to woo the nation's top high school baseball talent away from other programs or even the pro ranks. LSU, Texas and Florida are just three of the traditional powerhouses that have invested millions of dollars into lavish new or renovated stadiums in recent years.

THE LEADERS INVEST The University of Michigan recently spent $14.5 million to renovate its baseball and softball facilities to include state-of-the-art amenities.

THE LEADERS INVEST The University of Michigan recently spent $14.5 million to renovate its baseball and softball facilities to include state-of-the-art amenities.But the change has been apparent north of the Mason-Dixon line, too. More than half of the baseball programs in the Big Ten Conference alone, which actually boasted 10 teams this season (Wisconsin axed its varsity baseball program in 1991) and will have 11 with the addition of Nebraska next year, either have new or renovated stadiums, or they are in the fundraising or construction phases.

All this despite the fact that no team representing the conference has won it all at Rosenblatt since Michigan (1962), Minnesota (1964) and Ohio State (1966) took home national titles. And only one other school north of the Mason-Dixon line, the Pac-10's Oregon State, has won the national tournament since.

Why the sudden capital investment in Big 10 baseball facilities? In some cases, they're among the last venues on campus in need of replacement or modernization. At Purdue, for example, a $21 million project that will add a new baseball stadium with 1,500 permanent seats and full press facilities came about in earnest only after the university determined that it wanted to use the land currently being occupied by the Boilermakers' Lambert Field - built in 1955 - as part of a larger football stadium and arena expansion project.

At Michigan, $14.5 million worth of renovations to the university's baseball and softball complex - unveiled for the 2008 season - were added on to an extensive facilities master plan that features bigger-ticket items including a $21 million football practice facility and a $226 million renovation of the football stadium.

GOPHER IT Considering the precarious future of the Metrodome, the University of Minnesota is raising funds to construct a new on-campus baseball stadium.

GOPHER IT Considering the precarious future of the Metrodome, the University of Minnesota is raising funds to construct a new on-campus baseball stadium.And at Minnesota, the athletic department is in the process of raising the approximately $7.5 million needed to build a new stadium to replace 39-year-old Seibert Field. The fundraising has picked up pace since the Gophers realized they may not be able to play home games at the off-campus Metrodome, the future of which is tenuous since the Gophers' football team and the Minnesota Twins have moved into new stadiums. "People are realizing there is some urgency here," says Anderson, the winningest coach in Big Ten history, who has been advocating for a new on-campus baseball home for years. "We might not have a place to play, and our current facility on campus is in bad shape."

John H. Kobs Field, the home venue for baseball at Michigan State University, was similarly in bad shape until a sizable donation from Houston Astros owner Drayton McLane - now the stadium's namesake - made possible more than $4 million worth of renovations last year. "There were some schools, us included, that were falling behind in the race, and it was time to do something - not only just for us, it helps the whole Big Ten," says MSU head coach Jake Boss.

Purdue assistant athletics director Tom Schott, who acknowledges the difficulties inherent to running a northern baseball program in a limited spring season, likewise sees modernized baseball facilities as essential to keeping a program viable, even if the facilities aren't competing with some of the glitzier stadiums found in the South. "We're not building the fanciest stadium, but we are building contemporary, attractive facilities that fit in with the campus architecture," he says. "We have some bells and whistles, but we're not trying to outshine everybody."

The stadium that most escalated the baseball facilities race in the conference, however, is by all accounts Penn State's Medlar Field at Lubrano Park, a $31 million, 5,400-seat stadium with room for 600 more standing spectators. Prior to the venue's opening for the Nittany Lions' 2007 season, Penn State was yet another Big Ten school with outdated baseball facilities. "As a university, we embraced baseball just as America has, historically," says Penn State associate athletic director Greg Myford. "But from a resources standpoint, I don't think we've ever committed to baseball like we have in recent years."

BOILER ROOM A larger football stadium and arena expansion project at Purdue's campus necessitated that the baseball program find space for a brand new venue.

BOILER ROOM A larger football stadium and arena expansion project at Purdue's campus necessitated that the baseball program find space for a brand new venue.The project was only made viable through an operational partnership with the State College Spikes, an A-level, short-season minor league team that was previously located an hour's drive away in Altoona. The teams share the field, as well as underground batting cages, a players' lounge and locker rooms, and the Spikes generate a significant amount of revenue, although the facility remains under the university's ownership.

"The overall experience of attending a Penn State baseball game now is dramatically different," says Myford, adding that some of the program's longtime supporters struggled at first to come to terms with paying for admission to games that were previously free. "It has ended up that attendance for our baseball games is far exceeding what it was in the past. We need to continue to grow, and certainly the recipe for that isn't shocking - it's the combination of a winning program and putting adequate resources into marketing and promoting the program."

Only time will tell whether the new facility and related marketing efforts will translate into more on-field success for Penn State and other cold-weather schools. Myford and others, however, seem to agree that living with outdated facilities is one way to guarantee limited success, even by Big Ten baseball standards.

"Times have changed in college baseball," says Anderson, who has only had the opportunity to host a four-team regional once despite leading the Gophers to the NCAA Tournament 17 times. "Even within our league, we're seeing new facilities built and the competition for players continues to increase. And your facility, in my opinion, is a big statement about your commitment to your program."