Olive Stevens deadlifted more than twice her bodyweight at the AAU Junior Olympics in Des Moines, Iowa, this past July. It was one of four national and world records set by Stevens in the squat, bench and deadlift, as well as the combined total of all three lifts.

Stevens is six years old.

Extreme? Maybe not, considering she is the daughter of certified personal trainers who operate their own gym. According to the Capital-Journal of Topeka, Kan., Stevens has been lifting weights under close supervision since age three.

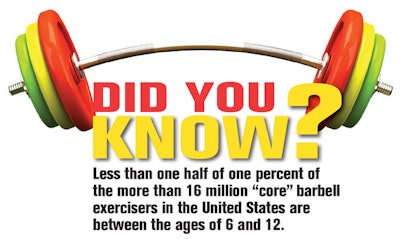

Unusual? Definitely. The Sports & Fitness Industry Association's 2014 Free Weight (Barbells) Single Sports Participation Report indicates that 6- to 12-year-olds make up less than one-half of one percent of the more than 16 million individuals in the United States considered "core" barbell weight-lifting participants (by engaging in the sport 50 or more times per year).

"That's not normal," says Larry Cooper, a certified athletic trainer at Penn Trafford High School in Harrison City, Pa., when told about Olive Stevens. "The medical community tends to think that you really shouldn't start doing competitive lifting until the growth plates are fused or closed [typically between the ages of 14 and 18]. The younger you put that stress on them, the more likely you are to have growth plate fractures."

Such injuries can haunt an athlete for life. "You can have a difference in the growth pattern for that extremity," says Cooper, who chairs the National Athletic Trainers' Association Secondary School Committee. "A leg could be slowed down in growth, become shorter, which creates all kinds of issues with the hips, back and knees. Growth patterns can be modified so they never are normal again."

SCALE BACK

That is not to say that youths can't participate in weight training, and reap the physical and psychological benefits that come with it. However, there are widely accepted guidelines — no one-repetition-maximum lifting, no overhead lifting and no unsupervised lifting — that have been in place for 30 years and supported by the ongoing strength-training research of Wayne Westcott and others. Says Westcott, instructor of exercise science at Quincy College in Massachusetts, "There's never been an injury report in any research study ever performed with young children."

That goes for children even younger than six, though Westcott says emotional maturity of children can be a challenge "if they can't focus, if they're not interested, if they're all over the place." But by age six, he adds, "they've been in a school environment, and they're a little more used to following directions. We found that six and up works really well in all respects."

Naturally, Westcott's youth strength-training studies are well-supervised, including carefully conducted one-rep-maximum benchmarks at the beginning and end of each study to measure its outcomes. In all other situations, Westcott is in the "no maximum" camp, as were even the 11 NFL teams that he worked with in the 1990s. There are ways to estimate an individual's maximum strength output without the heaviest lifting. "We know that what you can do five times is about 85 to 90 percent of what you can do once," Westcott says. "I'm not a big fan of one-rep maxes at any age, unless you're a competitive powerlifter or a competitive Olympic lifter. Then, obviously, that's your sport."

Westcott, who recommends anywhere from six to 15 repetitions per set for children performing a given lift, has found that kids who strength train while participating in another sport are best served by easing off weights while in-season. "Athletes who work really hard in any sport use a lot of their recovery energy in that activity. We found that during the offseason, strength training two days a week is just fine, as it is for anyone else who's a young preadolescent. Three days also works fine," he says. "But once they get into their competitive season, strength training one day a week works best. They will make the same gains as if they were training more frequently, and actually more gains because they are not overtraining."

BIG BROTHER

Supervision, another widely accepted youth strength-training guideline, doesn't necessarily mean that a qualified instructor is watching every single repetition of every single kid who wants to take up weightlifting.

Says Cooper, who's one of roughly three dozen coaches, physical education instructors and athletic trainers available to students at Penn Trafford, "They're not going to get one-on-one supervision, but they're going to get personalized education and training on how to use that weight machine to do the exercise properly for the first few times that they do that so they don't cause injury — making sure they have proper form, proper technique, proper breathing."

"Lifting in a controlled manner using muscle rather than momentum," adds Westcott, who introduced strength training to New York public schools in 1971, supervising 50 kids at a time. "They're lifting through the full range of exercise, rather than just a partial range to pump out partial reps."

Training expertise and facilities get harder to come by at the middle school and elementary school levels, where tried-and-true body-weight exercises such as push-ups and pull-ups suffice, so long as plyometrics (the practice of taking body-weight movements and adding height and distance) are avoided, Cooper says, since children typically lack the "foundation of strength" needed to avoid injury.

As a past employee at Southshore YMCA in Quincy, Westcott held hour-long beginner and advanced youth strength-training classes using kid-sized weight machines and roughly a three-to-one exerciser/supervisor ratio. "Trying to get youth into a facility doesn't work too well for profit, because they're in school all day and you don't want to keep them at night," he says. "You get them pretty much after school and before dinner."

Westcott is trying something new this fall, taking resistance bands into schools and testing the bands' youth strength-training effectiveness. Based on studies involving seniors, Westcott is encouraged by the non-intimidating nature of bands (no drop or pinch risk) and their ability to mirror the user's strength curve (less resistance at the start of a repetition). "Elastic bands are very good, especially for doing pressing or pushing exercises, such as a bench press, an incline press, a shoulder press or a squat," he says. "Band resistance seems to be a pretty good alternative."

Whether using resistance bands, body weight or kid-sized equipment (the Stevens' gym offers a 15-pound Olympic bar in place of the standard 45-pound bar for Olive, one of a dozen members under the age of 18), strength training should never intimidate today's youths. "It's the safest activity you can do," Westcott says, "as long as it's supervised and using good principles."

RELATED: Youth Weight Training Movement Still In Its Infancy

This article originally appeared in the October 2014 issue of Athletic Business under the headline, "Kid Power."