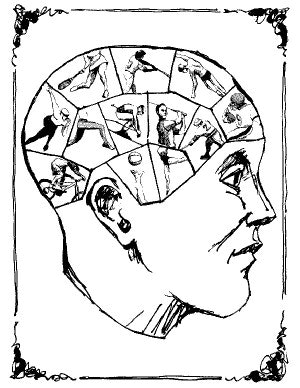

Getting into athletes' heads and hearts, sports psychologists say, will boost the effectiveness of their arms and legs

The 2003 Masters Tournament at Augusta National Golf Club was more than a meeting of the world's best golfers. While pros from different countries boasting varying levels of ability and utilizing diverse styles squared off on the tee, behind the ropes (or merely behind the scenes) the athletes were keenly watched by an assortment of sport psychologists with similarly dissimilar abilities, backgrounds and methods.

Although sport psychology has been practiced in both amateur and professional sports for more than a decade, outside of an Olympic year its presence has rarely been felt to this degree at a single premier event. Whereas perennial bridesmaid Phil Mickelson was derided by sports columnists a couple of years ago for utilizing visualization techniques - after Mickelson said, "I want to see the shot I want to hit. See the score and the round I want to play," Mick Elliott of the Tampa Tribune responded, "Didn't Chevy Chase say that once?" - sport psychology was the clear winner at this year's Masters. Ernie Els, who has credited his sport psychologist, Jos Vanstiphout, with bringing renewed focus to his game, finished tied for sixth. Also finishing near the top of the leaderboard were Retief Goosen, who won the 2001 U.S. Open title under Vanstiphout's tutelage, and Davis Love III, whose well-documented work with sport psychologist Bob Rotella boosted his confidence after a string of second-place finishes.

But first place went to what some have called "Team Weir" - Canadian pro Mike Weir (who won his first major), swing coach Mike Wilson and Utah State University sport psychologist Rich Gordin, who spent the week with Weir at Augusta National and pronounced him "locked in." Gordin explained: "He was just in control; he was ready to go play, I could tell."

Said Weir afterward, "I felt like I was in control of the situation."

This is the popular image of sport psychology: part science, part mysticism. Everyone knows that the human body reacts physically to mental stresses, just as everyone knows that certain athletes respond to pressure while others fold. No one agrees on the best way to fix the problem. And indeed, performance enhancement is just one aspect of sport psychology. These days, sport psychologists work with teams as well as individuals, with coaches and parents as well as with young athletes. Sport psychologists specialize in players who have broken down, and with those in championship form who still see room for growth. They work with middle-aged golfers and tennis players whose happy retirements are threatened by putting and backhand problems, and with teenage gymnasts whose lives are threatened by eating disorders. Increasingly, they work with artists, musicians, actors and corporate executives, applying the techniques that allow a baseball player to dig in against a 100-mph fastball to people suffering from stage fright or to those who are having trouble signing off on a $200 million deal.

Certainly, there are naysayers. During the 2003 Masters, Arnold Palmer blamed sport psychologists for destroying modern golfers' "emotion and toughness," while Chi Chi Rodriguez told a reporter, "I'd never let anybody who can't break 100 tell me how to play golf."

There is, also, a persistent stigma attached to psychology, sport or otherwise. As Dave Yukelson, coordinator of sport psychology services at Pennsylvania State University and a past president of the Association for the Advancement of Applied Sport Psychology (AAASP), says, "Sometimes the word psychology has a connotation of something being wrong - you've got to fix it, see the shrink. But really, we're dealing with human potential."

Oddly enough, sport psychology first took root neither in Western - not even West Coast - nor Far Eastern culture, but in the old Eastern Bloc, where it was applied in the Olympic domain beginning in the 1980s with spectacular success. (Or so it is said - exactly how it was determined that sport psychology was the primary catalyst for Eastern Bloc athletic success is shrouded in mystery.) In the 1990s, sport psychology began its shift to the West, becoming embraced within the world of professional golf, a sport that has coined an entire lexicon of mental failure. Also in the '90s, Phil Jackson brought sport psychology techniques and terminology to professional basketball, winning championships as coach of the Chicago Bulls and launching a successful second career as an author (Sacred Hoops, 1996) and motivational speaker.

Jackson's Zen approach clearly wasn't on the collective mind of sport psychology's original proponents. Olympians and Olympic coaches who first developed its precepts did so with scientific, not philosophical underpinnings. Utilizing what would become known as biofeedback, these pioneers were among the first to use electrodes and heart and brainwave monitors to uncover physiological responses in athletes in a variety of circumstances. Those who subsequently came to the field brought the philosophy, some tenets borrowed from the Buddhists (call it Zen and the Art of Free Throws) and some from the old Pac-10 (John Wooden is probably the most referenced Samurai of the Hardwood).

There is, as a result, evidence of a rift in the sport psychology field, caused mainly by the two distinct educational paths taken by practitioners. Some have studied sport psychology as part of their physical education coursework, while others have entered the field via advanced degrees in clinical psychology. One can see, perhaps, a form of sibling rivalry between those with counseling backgrounds and those with applied sports experience. For example, one prominent sport psychologist's web-site declaration, "I'm not a psychologist, I'm a sport psychologist," irks Jean Schweda, a psychotherapist with the Alliance Counseling Center in Colgate, Wis. Schweda says, "That's a lot like saying, 'I'm not a mechanic, I'm an auto mechanic.' Either you are or you aren't."

Both sides appear to be united, though, in their distaste for sport psychologists who enter the field promising results but boasting little in the way of academic or applied qualifications.

"Those web sites really concern me as a professional," says Yukelson. "Where's the quality control, the ethics and the competence? Maybe somebody's really into research, but doesn't have practical skills to convert theory into practice. Maybe the person doesn't know what he's talking about."

Gary Bennett, who counsels Virginia Tech students out of the school's Thomas E. Cook Counseling Center, notes that the term "psychologist" is legally protected, meaning that only licensed clinical psychologists can use it to describe themselves.

"Somehow, though, 'sport psychologist' is not a protected term," Bennett says. "There's no real accreditation process. There is a certification process through the AAASP, but you don't have to be certified to call yourself a sport psychologist. That creates some problems - you've got people out there advertising themselves as sport psychologists whose training and background might not be that solid." (Nonlicensed sport psychologists sometimes utilize labels such as "training specialist," "enhancement specialist" and "mental training coach.")

For many sport psychologists, licensed or otherwise, a successful client is all it takes to put the counselor onto the lecture circuit or to attract higher-profile clients. Athletes who don't perform after working with a sport psychologist, of course, aren't heavily advertised. (As in other pursuits, success in sport psychology has many parents, but failure is an orphan.) Frank Smoll, a member of the psychology faculty at the University of Washington, says that many would-be sport psychologists are in fact motivational speakers that include "pop-psych gurus who make millions of dollars with some very basic psychological principles," as well as amateur draft "experts" who claim to be able to tell an athlete's long-term abilities by reading his or her face. "Sport psychology is still a fairly new specialization," Smoll says. "You look around and you see that everybody is a sport psychologist. Ask them - they'll tell you."

It doesn't help that much of the language of sport psychology as it relates to performance enhancement - no matter how effective the techniques may be, and even when taught by its top practitioners - has the soft, squishy feel of pop psychology.

Not surprisingly, sport psychologists bristle at such a characterization. Yukelson insists, "Our field is very scientifically based. It's far advanced from the Eastern/Western thing."

Perhaps. But not even Yukelson's comprehensive "Mental Training for Baseball," available on Penn State's Morgan Academic Support Center for Student-Athletes web site, is immune, utilizing terms such as "attentional focusing" (a redundant-seeming part of concentration) and "feelization" (an aspect of visualization training).

On the other hand, much of psychology in general consists of techniques that aren't so much difficult to comprehend as they are difficult to consciously put into practice. Consider, as an example, a figure skater who performs perfect routines in practice but tends to falter in competition. After taking a history and establishing a rapport with the client, a counselor might suggest biofeedback as a way to show the client that certain mental truths have physical consequences.

"With biofeedback, you can tell right away when someone's got a problem," says Fred Newton, director of Kansas State University's University Counseling Services. "It's a physiological measure of arousal response.We hook them up and can tell when their muscles are tensing, when their skin is sweating, when their heart rate goes up - there are a hundred physiological responses. You can even detect it when they imagine themselves performing. We tested one catcher whose resting heart rate went from 60 to 95 when he just thought about making a throw to second base."

And then?

"We train them to regulate it, manage it," Newton says. In a parallel to Eastern philosophy, relaxation training typically involves breathing techniques, visualization and (borrowing from Eastern philosophy) a mantra in the form of a nonverbal ritual that helps the athlete treat every situation, no matter how much pressure, as if it were the same. Many athletes, Schweda notes, including golfers lining up a putt, basketball players approaching the free-throw line and baseball players stepping into the batter's box, already consciously or subconsciously perform these. "They do visualization, even if they don't call it that," Schweda says. "Basketball players will dribble to a point, pretend they have beaten their opponent, take the shot. Then they'll dribble to the same point, pretend their opponent is still guarding, then fake and take the shot. That kind of mental training can work together with their physical training."

Counselors also train their clients to understand that regulating physiological response works both ways - that is, the opposite mental state must sometimes be attained. Aynsley Smith, director of Sports Psychology Research at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., studied high school and minor league ice hockey goalies and found that their heart rates often average more than 170 beats a minute, in spite of the fact that they spend much of their time standing still. According to a recent story in The Baltimore Sun, Smith, an advisor to several college and National Hockey League teams, now counsels goalies not to relax but to psych themselves up to enjoy the rush of adrenaline.

"One of the most important mental skills is learning to control your arousal level," says Newton. "It's like going to sleep at night: People who can command their body to go to low arousal can fall asleep in seconds. People who can't reduce their anxiety toss and turn. The same thing happens at different levels of competition."

As an example, Newton points out that runners performing a sprint need to have a fairly high level of arousal, whereas milers need to be more relaxed. A further example, within team sports, is basketball.

"Games are won and lost on the foul line, and that's 90 percent mental," Newton says. "Kansas, which was statistically a better foul-shooting team than it showed, lost the national championship because players couldn't shoot at the foul line. I would even say the coach had something to do with it, because if you watched him during the game, he was very intense. Intensity is great for rebounding and keeping the flow of the game, but when you step to the foul line, you'd better not be intense, you'd better be relaxed. What he was communicating well, they did well, but what he wasn't communicating well, they did poorly."

Visualization, another vital skill, allows an athlete to prepare for a situation that cannot be simulated in practice. The purpose is both to boost confidence - "I've played Pete Sampras before, and what's more, I held my own against him" - and to do for the brain what practicing groundstrokes does for the reflexes. For some athletes, especially those whose sports require the endless repetition of a series of choreographed moves - figure skaters, gymnasts, snowboarders - it's hard to imagine training the legs but not performing a mental rehearsal. Visualization forces athletes to bring focus and intensity to their practice routine - bringing their game face, if you will - rather than merely going through the motions.

A related concept, simulation, is regularly used by teams facing a tough road game or post-season contest. Piping crowd noise into the practice field, practicing on similar surfaces or in similar weather conditions, and even practicing in conditions far worse than what is expected, can help a team cope better with adversity when the real game starts.

Along with dealing with stress and mental preparation, goal-setting is a major aspect of performance enhancement - and really, the very first step in the process. Essentially, sport psychologists believe that by choosing a specific performance (not outcome) goal - a personal performance target, say, or a certain skill to be acquired or improved - an athlete can attain "long-term vision and short-term motivation," as one sport psychology web site puts it. Goalsetting is central to nearly all of sport psychologist Terry Orlick's seven critical elements of excellence - commitment, focused connection, confidence, positive images, mental readiness, distraction control and ongoing learning - as laid out in his influential book, In Pursuit of Excellence. Newton says that when working with the Kansas State basketball team a few years back, setting the goal beforehand of improving free-throw shooting gave the team better focus in practice and boosted its confidence as the team's percentage rose - which it did, from the low 60s to the mid-70s in one season.

Yukelson, pointing to the spread of sport psychology principles into college and high school sports, says there's a wider implication of setting goals: personal improvement. It's something that athletes can bring to the table themselves, but it's also something coaches should know about. "Coaches are or should be concerned with getting kids committed to their sport," Yukelson says. "Commitment isn't about 24/7/365, or about showing up to every practice as a prerequisite to playing on the team. Commitment is about learning how to stay motivated, setting goals for yourself and committing yourself to improve."

As sport psychology's influence spreads, it's clear that psychologists are finding more willing and interested athletes than coaches. Athletes increasingly view it as another tool they can use to achieve their (presumably well-defined) goals, Bennett says. "When you get into competitive levels, people are looking for an edge," he says, "and this might be the thing that helps them bring it all together and get the most out of their abilities."

Many coaches, meanwhile, remain unconvinced of sport psychology's value. To some, it may seem too radical a departure from traditional coaching techniques; to others, merely old ideas put in a shinier package. Newton, though, suggests there could be another reason.

"Coaches have as much control over their domain as anybody in the world," he says. "Because of that, they're very wary of who they want to bring into the mix. They've brought in trainers, because they know the body has to work well, and on college campuses they include academic advisors because they know they have to make grades to be eligible. I've had some coaches work closely with me because they know that mental preparation is important, but others only call me in when they're completely baffled about something going on with a player."

Sport psychologists are developing programs targeting coaches because of their wide sphere of influence, but also because they seem to need it most. (As Yukelson puts it, "Most of the time you coach based on how you were coached. I'm not sure that's the healthiest model.") Newton, who is in the midst of a coach-oriented project, adds simply, "They're mostly from the old school. Older coaches knew there were ways to motivate, how to manage stress, but they learned it from the school of hard knocks, not from an understanding of what's going on in an athlete's brain and how to correct it. A lot of coaches do things, but aren't sure why they do them."

Many coaches - and, to be sure, many athletes - remain skeptical of anything that could be perceived as showing weakness. And certainly, the stigma that surrounds seeking help from a psychologist persists, even though (for example) a baseball player mired in a slump would not hesitate to seek out the hitting coach. But sport psychology is showing signs that it can overcome even the most resistant of athletes and coaches.

"You don't get a guarantee when you work with a sport psychologist," says Yukelson, "but I tell athletes, 'If you are interested in working on your mental game, and you commit yourself to learning certain skills, you will likely be more confident in yourself, because you're focusing on things you can control. You'll be more consistent, because you'll have a routine that will enable you to not have so many highs and lows. You can control the controllable.' "