Editor's note: This story originally appeared in Parks & Playgrounds, a new supplement to Athletic Business. View the entire digital issue here.

As soon as the weather warms up each year, many families flock to parks where their children can play and run around safely, interact with other children, cool off on the sprayground or simply enjoy being outside on a nice day.

In most communities, the first, best and usually closest option is the neighborhood playground. Playgrounds can be found in almost all communities, from densely populated cities to suburbs and small towns. According to the Center for City Park Excellence's City Park Facts 2014, there are 12,942 playgrounds in the nation's top 100 most populous cities alone (1,651 of which are in New York City). Playgrounds are so ubiquitous that The Trust for Public Land uses "playgrounds per 10,000 residents" as one of the five criteria for measuring excellence in its annual ParkScore assessment of big city park systems.

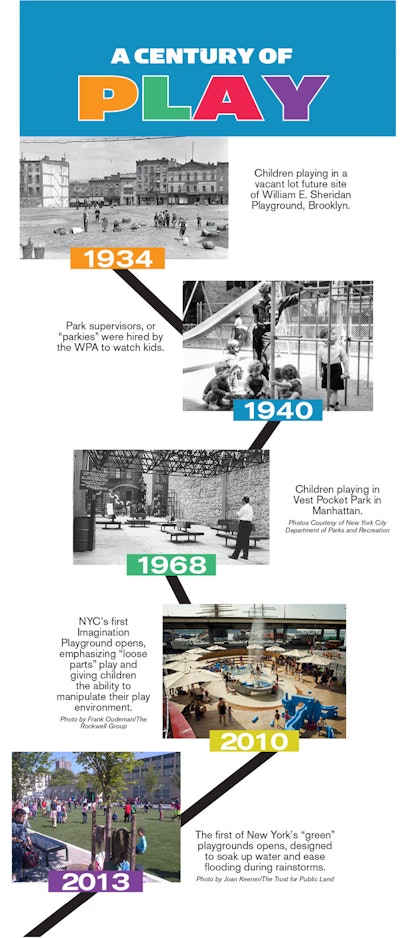

It hasn't always been this way. In fact, municipal playgrounds as a facet of life have only existed for little more than a century. The very first playgrounds were developed in New York City's crowded, impoverished neighborhoods at the beginning of the 20th century, when social workers and advocates for the poor used private philanthropy to build the first enclosed, safe areas for children who would otherwise play on the streets, in empty lots, or in the larger parks far from their homes. New York City adopted the privately developed Seward Park Playground in 1904, and the rest is history.

Playground design went through many evolutions, from the early dirt lots with fixed swings and merry-go-rounds, to the "cookie cutter" asphalt playgrounds of the 1930s composed of standard swings, slides, see-saws and monkey bars. By the 1970s, European-influenced, "adventure playgrounds" were introduced, featuring elaborate concrete and wood structures, often in the shapes of pyramids or tree houses, with large sand and water play areas.

The latter part of the 20th century saw the development of mass-produced unit play structures. Responding to the need for reduced maintenance and improved safety standards, cities embraced the modular play units, producing somewhat of a monoculture of playground design: attractive, durable and safe, but boring in the eyes of some users (and their parents).

After years of tight budgets, many cities are now turning their attention and investments to parks, with the newest generation of playgrounds attempting to marry the safety of current designs with the entrepreneurial spirit and attractiveness of the adventure playgrounds. Some designs even use the loose parts of architect David Rockwell's "Playground in a Box," designed as an "Imagination Playground" pro bono for New York City after his own children used the safe but repetitive playgrounds that dotted neighborhoods.

The latest development is the "green playground," driven by federal and local regulators on a mission to reduce the combined sewer overflow in their water systems. To that end, some city officials are allocating "green infrastructure" money to playground construction projects with special components. These high-tech play sites feature permeable pavers, synthetic turf fields that function almost like huge sponges and bands of trees and plantings that function as "rain gardens," all of which serve to capture falling rainwater and return it to the ground instead of the overburdened storm drain system.

BUILDING PARTNERSHIPS

As communities compete to see which can build the biggest, best and most fun parks and playgrounds, they must all confront the difficulty of finding the money to acquire land and build and maintain the equipment. This requires them to be as innovative in their development strategy as they are in playground design.

Public–private partnerships have been part of the solution. In the same way the nation's first playgrounds resulted from philanthropic interventions by reformers and public health advocates, partners — from neighborhood groups to big nonprofit institutions — are now priming the pump with fundraising, advocacy and, in some cases, design and construction. While most of these efforts are local, several national organizations are leading the way on playground creation. KaBOOM!, for example, is dedicated to eliminating "play deserts" — areas without adequate playspace. Since its inception in 1995, KaBOOM! has helped create nearly 3,000 playgrounds in the United States, Canada and Mexico.

The Trust for Public Land has been working to help develop parks in urban areas for four decades, partnering with cities to build new playgrounds and in particular to convert old, part-time schoolyards (most of which are large, empty sheets of asphalt) into fulltime playgrounds, serving students during school hours and the community when school is not in session.

The organization uses a strong community-engagement model that solicits and implements community suggestions in playground design. "At each school site, The Trust for Public Land works closely with students, teachers and neighbors to design a playground that meets the needs of the school and community," says Mary Alice Lee, director of TPL's New York City Playgrounds program. "By engaging the users of the park in a participatory design process over a three-month period, we channel their ideas and dreams into the creation of a playground that is perfectly suited for them."

TPL then works to raise the funds from public sources at multiple levels of government, as well as through private philanthropy. The near-instantaneous success of this program led to its adoption within PlaNYC, the sustainable development plan introduced by Mayor Michael Bloomberg that includes the goal of having every New Yorker live within a 10-minute walk of a park or playground. More than 250 schoolyards were converted into fulltime community playgrounds to help achieve this aim.

In many cities, local partners work to build new playgrounds and renovate existing ones. For example, in San Francisco, the City Fields Foundation works to transform asphalt lots into turf fields, and America SCORES, an organization that develops soccer programs in schools, similarly advocates for and helps bring about similar transformations across the country.

FUNDING CHANGE

So with cities building new playgrounds themselves, or nonprofit partners leading the way, what is standing in the way of an expansive and prolonged playground construction boom across America? As mentioned previously, the dearth of new playground development is due to inadequate (and sometimes decreasing) city park budgets. You can't blame local officials who hesitate to build new playgrounds even as demand is growing if they don't have the resources to maintain them.

Parks and playgrounds must be viewed as part of the bigger picture, where they are a partial solution to so many of the public health and environmental problems plaguing American communities. Furthermore, as many cities are engaged in an "arms race" to see which can be the most attractive to industry and innovators seeking a high quality of life, time and time again public green and play space is a deciding factor for businesses and individuals alike. When it comes to ensuring their lasting prosperity, cities can't afford not to have attractive, safe and fun parks and playgrounds.

While in a small number of cases, nonprofit partners can help relieve the maintenance burden, there is no substitute for fundamental city support for children's playgrounds. Local civic groups can play a helpful role by setting up "friends of" organizations that provide basic upkeep and extra eyes and ears on the playgrounds. Schoolyards that also serve as community playgrounds can have much of the daily maintenance provided by the school custodian staff. New, state-of-the-art play equipment is designed to be quite durable, so regular investment in a capital replacement of outdated playground equipment and worn safety mats is also important and can reduce daily maintenance costs going forward.

Creative partnerships between various public agencies, or with non-profit and volunteer groups, can go a long way toward making sure that a community has first-rate play spaces. But the largest responsibility for ensuring that a community is safe, livable and fun lies with our local governments, and the residents who pay taxes, vote and count on public services.

Need more ideas to develop play in your community? Check out these sites:

The Trust for Public Land

KaBOOM!

City Parks Alliance

City Fields Foundation

America SCORES

Adrian Benepe is senior vice president and director of city park development for The Trust for Public Land. This article originally appeared in Parks & Playgrounds with the headline, "Play Together."

MORE FROM PARKS & PLAYGROUNDS