When a Dallas Cowboys practice facility collapsed under a microburst of 60-mile-per-hour winds in May 2009, it injured a dozen people and proved fatal for the company ultimately responsible for the facility's manufacture.

Fabric structures are often seen as a more feasible alternative to brick-and-mortar construction, particularly in times of economic recession. (Photo courtesy of Yeadon Fabric Domes)

Fabric structures are often seen as a more feasible alternative to brick-and-mortar construction, particularly in times of economic recession. (Photo courtesy of Yeadon Fabric Domes)When a Dallas Cowboys practice facility collapsed under a microburst of 60-mile-per-hour winds in May 2009, it injured a dozen people and proved fatal for the company ultimately responsible for the facility's manufacture. And while the intervening years have brought the fraying effects befitting a well-publicized public-relations disaster involving more than $35 million in legal settlements (so far), the fabric structure industry at large is still standing strong.

"The Dallas Cowboys thing, without a doubt, was top of mind when discussing an opportunity with a prospect - whether an architect, an engineer or the end user," says Barry Goldsher, CEO of South Windsor, Conn.-based Farmtek, makers of ClearSpan frame-supported fabric structures, a relatively new brand in the sports and recreation marketplace with fewer than 10 installations. "The fact that a fabric structure came down really hasn't put a kibosh on the tremendous benefit of using one. It still outperforms a steel building - not only in upfront cost, but in the cost over the lifetime of the building."

The Total Athlete Indoor Training Center in Triadelphia, W.Va., accommodates a variety of activities under one roof. (Photo courtesy of ClearSpan Fabric Structures)

The Total Athlete Indoor Training Center in Triadelphia, W.Va., accommodates a variety of activities under one roof. (Photo courtesy of ClearSpan Fabric Structures)Even companies that have been providing sports and recreation solutions for decades found themselves battling misperceptions about what took place two-and-a-half years ago in Irving, Texas, under the auspices of Canadian-based Cover-All Building Systems, whose wholly owned subsidiary, Summit Structures LLC of Allentown, Pa., designed the Cowboys facility. "That rippled through our industry in a big way, because it was called a dome - the Dallas Cowboys' dome - and it was actually a frame-supported structure," says Steve Flanagan, president of air-supported structure manufacturer Yeadon Fabric Domes in St. Paul, Minn. "If I'm in front of a building official, that's one of the first things asked: 'Did you make the Dallas dome?'"

"You have to explain," adds Jim Avery, vice president of Sprung Instant Structures, which manufactures frame-supported buildings. "People also think that if they have a bad experience with fabric structures, they should eliminate that product category from consideration altogether. We've had to be very aggressive in trying to educate clients. I recommend to anybody looking at fabric structures, especially frame-supported ones, that they go see two or more examples out there. Basically, a company can't just open a welding shop, go buy fabric and say it's in the fabric structure business."

A stressed-membrane structure turned one of two outdoor pools at the Kearns Oquirrh Park Fitness Center in Kearns, Utah, into a natatorium. (Photos courtesy of Sprung Instant Structures)

A stressed-membrane structure turned one of two outdoor pools at the Kearns Oquirrh Park Fitness Center in Kearns, Utah, into a natatorium. (Photos courtesy of Sprung Instant Structures)One could argue that Cover-All, at one time North America's largest supplier of pre-engineered membrane building systems, is no longer in the fabric structure business because of overstressed frame members discovered in the Irving wreckage by National Institute of Standards and Technology investigators, who released their final report on the collapse in January 2010. (The failure occurred despite efforts in 2008 to reinforce the then-five-year-old structure.)

Cover-All's figurative roof caved in shortly thereafter. The company suspended manufacturing operations in March 2010, and president and CEO Nathan Stobbe soon authored two letters - one warning clients that existing facilities were not to be used in severe weather "such as snow, sleet, freezing rain and winds in excess of 35 mph." The next, dated April 23, 2010, noted that the company could not fund its internal design-review process to completion and therefore could no longer make specific safety recommendations regarding its product line. Stobbe admitted that "there has been an initial determination that some of the structural members and connections for some of the spans of certain buildings manufactured by Cover-All Building Systems Inc. may not meet the present combined wind and snow load capacity requirements of applicable building codes." NIST analysis had found that the Cowboys structure failed in winds of 55 to 65 mph, still 25 to 35 mph shy of established industry standards for wind tolerance.

By June 2010, settlements were reached in lawsuits filed against Summit Structures and Cover-All by Cowboys special teams coach Joe DeCamillas, who suffered a broken vertebra in the collapse, and team scout Rich Behm, who was rendered a paraplegic. That same month, Cover-All's assets were purchased by Canada's Norseman Structures Inc., whose press release announcing the acquisition stated, "Norseman Structures' commitment to excellence goes beyond other industry competitors, such as Cover-All, as our designs are engineering [sic] to meet and even exceed industry standards."

Building codes pertaining to fabric structures, which Yeadon's Flanagan describes as "very complicated," have not changed since the Dallas collapse. "But it can be a long, drawn-out process to change them," he says, "so that does not mean something is not in the works."

Changes to accepted industry standards have been slow to come, as well. Referring to the Dallas collapse, Peter Bos, head of engineering at Sprung Instant Structures and a member of an American Society of Civil Engineers committee that creates such standards, says, "We discussed it, but as of yet we haven't made any recommendations."

Immediate reaction came instead from insurance policy writers, according to Flanagan, who adds, "That creates an issue with everybody's structures, because if you can't get a building insured, no one's going to buy it from you."

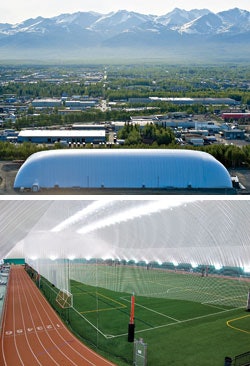

The 180,000-square-foot BEK Sportsplex in Anchorage houses a 400-meter track. (Photos courtesy of Yeadon Fabric Domes)

The 180,000-square-foot BEK Sportsplex in Anchorage houses a 400-meter track. (Photos courtesy of Yeadon Fabric Domes)It's hard to speculate how an air-supported structure might have fared in the face of the Irving microburst, but Flanagan notes such structures are designed to withstand 150-mph winds. "They have been struck with microbursts before and have held up," he says. "Then again, what you can't control is if there's an object flying through the air that can hit a dome and puncture it. The thing that I always mention to people is that there are no heavy objects overhead in an air-supported structure, so there is nothing that can really collapse on top of anybody other than fabric."

And perhaps not even that. Depending on the size of the opening and the air volume being mechanically forced into the space, an air-supported structure can "function for a long time with a hole in it," Flanagan says.

Another advantage of air-supported structures is that they can be put up and taken down with relative ease. That said, permanent applications are increasingly common. "The bread and butter of our industry started out as tennis and swimming, because it was a good seasonal building," Flanagan says. "Now, the focus is on multisport facilities serving turf sports like soccer, lacrosse, softball and baseball." One 180,000-square-foot Yeadon installation in Anchorage, Alaska, covers a 400-meter track.

As with all cold-weather installations, snow loads are shed by the curvature of the structure. The failure of the nearly 30-year-old Metrodome roof last December in Minneapolis - with video of an avalanche of snow cascading through overstressed fiberglass fabric to the synthetic turf below making the television and YouTube rounds - meant still more damage control for manufacturers like Yeadon, though the similarities between its products and the Metrodome's Birdair-manufactured roof end with the concept of air support. "Even though that structure is a different technology, a different type of fabric and a different type of use, it backlashes our industry again. We hear about it," Flanagan says. "Everybody hears about it, because the national media picks it up, and it doesn't take much now with the Internet to get bad information out in a big hurry." (It's worth noting that Birdair was chosen to replace the Metrodome roof earlier this year.)

Snow loads are accounted for in Sprung structure designs by the rigidity of individual Kevlar® membrane panels stressed horizontally and vertically between aluminum framing members at 1,500 pounds per square foot and pitched at a 26-degree angle. "Forces on the membrane that are built into the design give it the rigidity so that snow slides off it and wind simply hits it and moves over it," Avery says. "You get a lot more longevity in the product."

Sprung structures, some of which are functioning more than 30 years after installation, are designed as permanent building solutions, though they can be expanded or disassembled and relocated. They can be specified with 9-inch-thick, R-30 insulation sandwiched between two membranes, as well as HVAC and fire-suppression systems and architecturally aesthetic windows and doors made of glass. But all of these features come at a price. "In comparison to competitors like Cover-All, our structure is significantly more money, and there's a reason why," Bos says. "We use different materials in order to ensure that this structure will indeed stand up as designed in these types of wind pressures. In fact, we have structures out along the Atlantic Coast that have survived hurricanes quite well, whereas the adjacent structures simply blew away. We take our engineering extremely seriously."

"This isn't a low-cost solution," Avery adds. "This is a faster, smarter, better value proposition, because of the energy efficiency and the long-term flexibility."

In the past, cost-effectiveness and speed of construction (occupancy is possible within months of most orders) have made the fabric structure industry relatively unflappable during economic downturns. The current one, however, has been particularly burdensome.

"Typically, the fabric structure industry has done better in recessions because it is a less expensive building - less cost per square foot than brick-and-mortar buildings," says Flanagan. "But the length of this recession, the endurance of it, has meant limited budgets for recreation programs. Those are the budgets that seem to be cut first by municipalities and institutions. So, the business in this industry is down some over past recessions, but the inquiries are starting to come back and things are starting to turn."

In a Darwinian sense, the Dallas collapse and the subsequent folding of Cover-All may actually work in surviving manufacturers' favor. Farmtek's Goldsher, for one, thinks so. "We grew like gangbusters, because Cover-All was gone and that low price on the street, for municipal work especially, was gone," he says, adding that while his company sells 40 salt storage enclosures a week, its recreation market coverage has only just begun. The company advertises in more than 250 magazines and sends out more than 20 million direct-mail pieces each year. "We spend money to generate interest in a fabric structure versus steel or bricks and mortar," Goldsher says. "It's a huge potential market. There are some fabric structure manufacturers that have focused on it and have built relationships with schools and universities, so we do have some work to do. But we're very interested in providing solutions for that market."