![[Photos courtesy of HOK]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2016/12/ab.PracFac1116_feat.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&q=70&w=400)

This article appeared in the November | December issue of Athletic Business. Athletic Business is a free magazine for professionals in the athletic, fitness and recreation industry. Click here to subscribe.

Nate Appleman is a global director of the Sports + Recreation + Entertainment practice at HOK’s Kansas City, Mo., office.

Nate Appleman is a global director of the Sports + Recreation + Entertainment practice at HOK’s Kansas City, Mo., office.

The NCAA restricts student-athletes' in-season practice to 20 hours per week, or four hours per day. The student-athletes themselves put in this practice time while also attending classes and fulfilling their various other obligations around campus. It might sound absurd to begin counting the minutes they spend in transit, but those minutes add up. Time spent reaching athletics facilities, and time lost in a maze of corridors in older athletics facilities, eats into the hours devoted to practice and coaching on a daily basis.

Carrying out the design of successful training venues requires that architects exhibit sensitivity to the needs of athletes and coaches and, because most such facilities are built in the vicinity of older competition venues and practice fields, take into account those facilities' locations and adjacencies. In the case of a training facility that will serve all student-athletes on campus (rather than just the football or basketball programs), the specific needs of each program must be taken into account. It all makes the designer of training facilities a pragmatist and a bit of a visionary, too — versed in the minutia of athletes' and sports programs' daily routines, but also given over to big-picture awareness of the flow of students everywhere on the athletic and academic campuses, and how those different groups could ideally intersect.

![The Ragin’ Cajuns Athletics Performance Center at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette was designed to minimize time student-athletes spent transitioning between program areas. [Photos courtesy of HOK]](https://img.athleticbusiness.com/files/base/abmedia/all/image/2016/12/ab.PracFac1_Lg.png?auto=format%2Ccompress&fit=max&q=70&w=400) The Ragin’ Cajuns Athletics Performance Center at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette was designed to minimize time student-athletes spent transitioning between program areas. [Photos courtesy of HOK]

The Ragin’ Cajuns Athletics Performance Center at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette was designed to minimize time student-athletes spent transitioning between program areas. [Photos courtesy of HOK]

Click to enlarge

Click to enlarge

A SPACE/TIME CONTINUUM

The big-picture aspect of training facility design is particularly important, as one of the most critical planning decisions athletics administrators must make is whether, in the name of efficiency, athletes should have all their needs met under one roof (or under adjacent roofs). It is a central question on nearly all campuses where new training facilities are being contemplated. Should athletic training facilities incorporate academic or dining facilities, as a way to be more efficient with available time? Or does this more-efficient plan lead to too much separation between students and student-athletes? It's a trade-off that weighs heavily on a lot of administrators' minds. (See page 72 for an example from the University of Kansas.)

Most coaches, if asked, would express a preference for keeping athletes' academic, dining and strength training facilities close together in the interest of condensing athletes' days. But that sort of plan has the potential to ensure that athletes would hardly ever set foot on campus. Even Jack Swarbrick, university vice president and director of athletics at Notre Dame, counts himself as a proponent of creating an environment where there is little distinction between students and student-athletes, even as the forthcoming Campus Crossroads Project will reposition Notre Dame's football stadium as a year-round hub for academics, athletics and student life.

More from AB: Designing a Sports Performance Facility

At the University of Louisiana-Lafayette, which recently opened the new 85,000-square-foot Ragin' Cajuns Athletics Performance Center, the thinking was similar, with a limited budget being another strong impetus to decide against adding an academic or dining component specifically targeted to student-athletes. In ULL's case, existing academic and dining facilities already sat close together, and although linking up all athletics-oriented facilities was talked about extensively, administrators eventually made a conscious effort to keep those components where they were.

The other big-picture issue in training facility design is how to balance the needs of football with those of every other sport. By its nature, the football program — with 120 athletes who train together and in separate units, overseen by corresponding teams of coaches — can end up taking over a building. The scale of locker facilities, team meeting rooms, and equipment storage and issuing space dwarfs the facilities required by other sports programs, and the allocation of smaller meeting rooms that can accommodate different football positions or units — as well as office space for the larger coaching staff — can crowd out other programs or make them unable to take advantage of the building's promised efficiencies.

RELATED: College Training Facilities Marry Functionality, Experience

At ULL, HOK met with each of the coaching staffs to discuss the different team needs during development of the master-planning document. After football, the highest-profile and most-equipment-heavy squad is the baseball team, and designers met with head baseball coach Tony Robichaux about his team's particular requirements. Each of the coaches of the other sports programs had an opportunity to weigh in on the design process even if the programmatic pieces specific to their teams were much smaller than the football side of things. They gave input on everything from the relative size of visiting team locker rooms to the layout of the athletic training area and weight room, and their connectivity to other spaces and to adjacent buildings and fields.

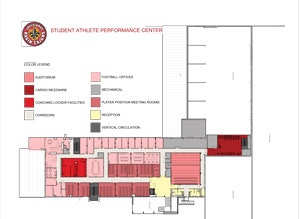

The new facility, developed as a design-build project in conjunction with Architects Southwest and Lemoine Construction of Lafayette, is essentially attached to the Leon Moncla Indoor Practice Facility, expanding that building's ability to effectively serve all student-athletes with convenient access to an existing 100-yard indoor field. Care was taken to give all sports programs direct access from Moncla into the weight room and athletic training space, something achieved in part by placing football coaches' offices, staff rooms and position breakout rooms on the second floor, where coaches can also enjoy views to the outdoor practice fields and Cajun Field, the Saturday home of the Ragin' Cajuns. Building components used by all athletes — including the auditorium and sports medicine, athletic training and weight training areas — sit on the first floor. Usable space (and athletes' time) is maximized through diminished corridors and the placement of programmatic spaces as close together as possible and in a logical progression.

Coaches’ offices and dministrative spaces are located on the second floor, leaving the first floor open for student-athletes to easily access weight room and training spaces.

Coaches’ offices and dministrative spaces are located on the second floor, leaving the first floor open for student-athletes to easily access weight room and training spaces.

FITING EVERYTHING IN

The master plan for the school places the new Athletics Performance Center on the eastern edge of a future "Athletic Quad," an enormous tailgating plaza designed to promote the Cajun gameday atmosphere for football, tennis and baseball contests. The planned demolition of the former Cox Communications Athletic Complex is all that is standing in the way of completing the quad.

That former athletic complex comprised 25,000 square feet, or 60,000 fewer than the new building. As befits a facility counted on to impress recruits, the new performance center is packed full of high-tech equipment, from strength to video; a theater-style, 150-seat auditorium with state-of-the-art video and sound; locker facilities laden with a laundry-list of amenities, including 14 flat-screen TVs; and an athlete lounge and hydrotherapy suite, also complete with multiple flat screens. The designers were challenged to architecturally craft a building abutting an enormous pre-engineered structure (the Moncla practice facility) for an athletic department that had determined that the vast majority of the money should pay for what's inside and how it will transform the athletes' experience. For Mark Hudspeth's football Cajuns, the demolition of the Cox Center will pave the way for a mere 15-yard walk from the training performance center to the Cajun Field tunnel.

Tucked into this space is a building that is both highly functional and a recruiter's dream. The student-athletes may not be cognizant of the minutiae of the facility's planning, but the time savings will show on the field, and in the classroom.

This article originally appeared in the November | December 2016 issue of Athletic Business with the title "How efficient training spaces can maximize limited practice time"