The Putney School, a private, progressive secondary school in southeastern Vermont, sits on 500 acres that include a dairy farm, stands of sugar maples, vegetable gardens and hay fields.

(Photo courtesy of The Putney School)

(Photo courtesy of The Putney School)The Putney School, a private, progressive secondary school in southeastern Vermont, sits on 500 acres that include a dairy farm, stands of sugar maples, vegetable gardens and hay fields. The farm is a laboratory, if you will, or a classroom - all of the school's 220 students will work there for at least one trimester during their time at the school - but it is also deeply symbolic of the central position in the curriculum given to what the school calls "the dignity and relevance of physical work."

Over the years following the school's 1935 founding, "sustainability" was a concept that was primarily limited to the farm itself. Students in the dishwashing crew oversaw the collection of table scraps for feeding the pigs and composting, the barn crew collected manure from the troughs to be spread in the fields, and wood selectively harvested from school grounds was taken to the on-site sawmill for use in building and arts projects. At the end of the day, the students (including this author, a 1979 graduate) returned to their dorms, many of which were converted barns and out-buildings that featured overloaded electrical systems, decades-old radiators and little to no insulation.

But the school's newest building is changing all that. The Putney Field House, which opened in October 2009 (and achieved LEED Platinum status this May), is a laboratory and classroom, and is deeply symbolic of the school's renewed commitment to full sustainability on its campus. It's actually more than that - as the nation's first secondary school building to generate more energy than it consumes, the field house is being seen as the (presumably, compact fluorescent) light that will illuminate the road ahead for other schools and architects.

"The goal was for it not just to be for this school," says Randy Smith, Putney's business manager. "The kids who graduated this year will go off to college, and colleges are big on saying to constituents and students, 'We're going to build a dorm or a field house or dining hall, and we'd like your input.' We've sent off a group of students who, when that happens, can say, 'We'd like it to be net-zero.' And when the school says that's too expensive, they can say, 'Oh no, it's not, and I know where you can go to find that out.'"

Among the false assumptions likely to be made about the $5.1 million, 16,800-square-foot field house is that its net-zero operability is made possible by its small size - or by money. On the contrary, Smith says, "There's nothing fancy or complicated about what we did. We just did more of some things, like insulation, and made sure that tolerances were much better than they would be if it were a code building. Just getting the insulation and siding right was 60 percent of the battle."

Danielle Petter, research director at Waitsfield, Vt.-based Maclay Architects (she's currently at work on Putney's campus-wide master plan), confirms Smith's assessment, laying out the net-zero particulars in five areas:

The building's roofs, walls and floors - and even the bases of support posts - are packed with rigid insulation, spray-on foam and dense-pack cellulose. (Photos courtesy of The Putney School)

The building's roofs, walls and floors - and even the bases of support posts - are packed with rigid insulation, spray-on foam and dense-pack cellulose. (Photos courtesy of The Putney School)-

Insulation. "It's pretty much double what you'd see on typical new construction," Petter says: R-60 roofs, R-45 walls and R-20 below grade (foundation walls and under slab), utilizing a combination of rigid insulation, spray-on foam and dense-pack cellulose. Windows are low-E and triple-insulated, and the building envelope was carefully detailed to avoid thermal bridging and air infiltration. The only snag during construction was a misadventure involving dense-pack insulation - essentially ground-up newspaper that is pumped in, slightly damp, like shotcrete - that was initially too densely packed and shoved wood studs three inches overnight as it dried. Smith says, "We put in an awful lot of insulation, but in the scheme of things, that didn't add 1 percent to the cost of the building."

"A high-performance building envelope provides a lot of benefits," Petter adds. "If you have a highly insulated building, once you heat your air up to a certain temperature, it doesn't lose its heat very quickly. You could heat this building up in the middle of winter, turn all your systems off, and it would maintain an internal temperature for two or three days that would be comfortable."

- Daylighting. Large-volume spaces are a challenge from an energy-efficiency standpoint not because the greater volume requires more air conditioning or heating, but because it hinders daylight penetration. Daylighting, a net benefit because it both reduces the need for artificial lighting and aids in passive solar heating, is achieved through carefully sited windows and skylights, reflecting blinds on south-facing windows and sensors that keep electric lighting off unless ambient illumination falls below a preset level or the system is overridden.

-

Siting. Smith calls the field house "a harvester of solar heat," but concedes it isn't sited as well as it could be for energy purposes. There was some grumbling from members of the Putney community that the field house as sited blocks the view north from the KDU (the kitchen dining unit - the school's traditional social gathering space) to the valley and Mt. Ascutney beyond, but the sentiment prevailed that maintaining views from the KDU and offering views from within the field house were less important than making the building as high-performance as possible. Ultimately, the field house was set back a bit more from the dirt road east of both buildings, but the panoramic view of the Green Mountains has been compromised - and moreover, there are very limited views out of the field house's north side.

"Opening a building to the north is never something that's really beneficial, and it would have required a higher energy intensity for the building," Petter says, referring to a measurement used throughout the building industry reached by dividing the total amount of energy consumed by the number of square feet. "When you're looking at a high-performance building, it comes down to percentage points."

"It was a trade-off," Smith says. "Some people knew exactly, visually, what they were losing. But if we'd built it down the hill or in a number of other locations, it would have been harder to manage and a destination building only for athletics. We also wanted people to see it. It's fine to have a net-zero building, but we wanted it also to be a statement."

-

Solar power. The field house is powered by 16 sun-tracking photovoltaic solar panels, with excess energy captured by local grid operator Green Mountain Power. Paid by the company 13 cents per kilowatt-hour produced plus a 6-cent premium, the school racked up a credit of $3,800 in its first 12 months of operation, and received an initial account-clearing check this spring for $2,900. "Solar is getting more efficient, and having the tracking system definitely makes it more efficient than a static system," Petter says. "But the main thing is that we were able to reduce the loads on this building." According to Petter, the field house's energy intensity is 9.6 thousands of Btu per square foot per year. Typical office buildings functioning today are in the range of 80 to 110 kBtu, and the place where buildings can achieve net-zero capability is something below 25.

"There are still financial tradeoffs," Petter says. "Until you spend enough money to get your building down to performing below that level, it doesn't make sense to pay for the extra photovoltaics. You can put more PV or insulation in, but at those higher energy intensity levels, you can get more bang for your buck with insulation."

-

Mechanical systems. The field house uses air-source heat pumps, which (because they don't require the drilling of wells) cost less than ground-source pumps, but are less efficient. Petter says, basically, so what. "We saved about $100,000 in capital costs, and only had to spend about $35,000 more in increased PV," she says.

Operationally, the cutting-edge technology - more accurately, an update on an extremely old concept - is night flush mechanical cooling, in which operable clerestories are programmed to open during the coolest part of the night, flushing warm air out of the building and replacing it with cooler air brought in through apertures placed lower to the ground. The system measures both the building's interior air temperature and the differential in ingoing and outgoing volume, and when appropriate levels of both have been reached, it shuts off and the windows close.

"Because the field house is super-insulated, it takes a minimal amount of heat to keep the building warm in the winter," Smith says. "In the summer, we can capture cool night air, hold it in the building, and we don't need to air condition. The insulation works both ways. The field house doesn't have air conditioning, but it's perfectly comfortable and functional in the summer months."

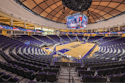

Smith's many tours of the field house for people interested in the building's sustainable aspects begin with the monitor on the wall adjacent to the south entrance that shows rates of solar energy production and energy use by various building systems (the real-time data monitoring system can be viewed online; enter "student" for both username and password). Past the plant manager's and athletic director's offices, tours stop by the fitness center, where rowing, cycling and elliptical machines harness the energy of exercisers to run their consoles. Visitors then linger in the building's largest space, the gym. But for Smith, the mechanical room is a highlight and an apt ending point.

"The mechanical room has huge collection tanks for the composting toilets, but it takes people a minute to think when I ask them what's missing," Smith says. "People say it doesn't smell like a basement, because there are no oil or propane tanks. There's none of that. It's all electric."

The sun-facing field house is flanked by the solar array and the KDU. (Photo by Jim Westphalen, courtesy of Maclay Architects)

The sun-facing field house is flanked by the solar array and the KDU. (Photo by Jim Westphalen, courtesy of Maclay Architects)The field house is "all those very cool things that we were hoping it was going to be from the get-go," in Smith's words, but there was a moment during the planning process when it was not clear that the school could make the full commitment to a net-zero building. The school had selected Maclay Architects, a specialty firm that bills itself as offering "choices in sustainability," and principal Bill Maclay had laid out three choices - a standard building that would be 10 percent more efficient than current codes require (estimated to cost around $3 million), a high-performance building that nevertheless had a carbon footprint, and a net-zero building that could generate enough power to offset whatever energy was used throughout the course of the year (early estimates, which included operational systems not included in the final design, pegged this option at $4.5 million).

"We had already made a decision institutionally that our next capital building project was going to be sustainable, and we had done some very rough modeling around return on investment," Smith recalls. "I'm always leery about those kinds of things, because all I need to do is escalate the cost of fuel oil 20 percent a year rather than 11 percent, and the payback becomes half as long. But it was clear that fuel oil prices were not going to go down in the long term, and it was clear that the differential between a 10 percent efficient building and a net-zero building was probably worth the capital investment. And equally important, it was worth the choice as an institution to do that."

All that said, the moment seemed fraught with uncertainty.

Inside, the view to the north is limited. (Photo courtesy of The Putney School)

Inside, the view to the north is limited. (Photo courtesy of The Putney School)"At the time, it was a very hard decision to make, because it was the third quarter of 2008," Smith continues. "Virtually every capital project at every school was being canceled, and we were just about to approve one. And not only approve one, but the most expensive one on the menu. The flip side of that was that oil was trading out at $147 a barrel, and we could point at that and say, 'We don't think this is a permanent price, but on the other hand, this is an indicator of what's going to happen.' We had brought together the architect who could design it with a presentation that made sense, and we were at a moment in history where we were presented with this stark reality of the price of energy. It was actually Ira Wender, a long-term board member who was the chair of the finance committee, who said, 'I don't think we have any choice. We have to pick a net-zero building.' I hesitate to use the word 'moral,' but the financial and the right thing to do were exactly the same. It would have been really difficult to say, 'Well, we shouldn't spend the extra $500,000 for the power generation because oil's probably going to get cheaper.'"

The continuous monitoring of energy use is helping the school protect its investment. Smith can check in with the field house on his phone, and students and staff members who have become well versed in accurate reading of the data in effect are serving as extensions of the operations staff.

"I have a trustee who's very interested in the hour-by-hour streaming data, and he will send me an e-mail that says, 'Randy, there was a light on in your building overnight,'" he says. "We can pay close attention to how well the controls are working, and we've been lucky - the building has performed better than we modeled both in the reduction in energy use and the production of energy by the solar array."

While the current student body is getting a lesson in energy input and output, waste flows and the like, the school has learned - and is insistent on teaching to others around the country - that net-zero buildings are not a futuristic concept.

"I think what's really important about the building is that it shows that you can create a building that is built with the people and the environment in mind, that creates as much energy as it uses, and you can do it right now, and it's not going to break the bank," Smith says. "That technology isn't five years out. If we had the will, as a state or as a nation, we could make our building codes to the specifications of this field house, and all of a sudden you'd see energy consumption in our country plummet."