Ninety minutes before tipoff of the first basketball games scheduled in the Archie (Mo.) R-V School District's new gymnasium on Jan. 20, staff members were still cleaning up from its seven-month construction.

Multicolored brick and a bright entry prevent the Archie (Mo.) R-V School District's new monolithic dome gymnasium from looking like it

Multicolored brick and a bright entry prevent the Archie (Mo.) R-V School District's new monolithic dome gymnasium from looking like it

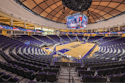

With mere minutes to spare, the girls' varsity basketball team entered the arena to great fanfare, as AC/DC's "Thunderstruck" boomed over the sound system and a fog machine added drama. That scene was repeated when the boys' varsity team took the court later that night. Both Whirlwinds teams went on to score convincing wins over Amoret's Miami High, launching a new era for Archie R-V athletics — indeed, for this entire town of 1,000 residents — in a modern-day facility that looks like something straight out of the 1970s.

That's right: Archie's $4.9 million gymnasium is a 43-foot-high monolithic dome that spans 140 feet in diameter. Constructed with a ringed brick foundation as its base, the structure consists of tough inflated fabric (which serves as the roof) insulated with rebar, shotcrete and polyurethane foam. The gym's curved shape will allow it to withstand an F5 tornado and double as a community storm shelter. In fact, the Federal Emergency Management Agency provided the district with a $1.1 million grant to help pay for construction. The concrete's thermal mass keeps temperatures within the dome from fluctuating, allowing the dome to use at least 50 percent less energy for heating and cooling than a traditional gymnasium structure — savings that are expected to cover the project's entire cost within 20 years.

"I had never heard of a monolithic dome until the fall of 2009," says Sean Smith, superintendent of the Archie R-V School District. That was when a school board member who works in the concrete industry presented his colleagues with a trade magazine article about monolithic domes. "We were curious," Smith says, "so we spent a lot of time investigating the benefits, and it just started to make sense."

Interior walls and a dropped acoustical ceiling give the bronze-colored Eagle Dome in Woodsboro, Texas, an intimate feel. (Photos courtesy of Leland A. Gray Architects and Woodsboro Independent School District)

Interior walls and a dropped acoustical ceiling give the bronze-colored Eagle Dome in Woodsboro, Texas, an intimate feel. (Photos courtesy of Leland A. Gray Architects and Woodsboro Independent School District)Monolithic domes began popping up in the United States in the '70s. South claims to have built the first one in 1975 (a potato storage facility in Idaho). Since then, additional bulk storage facilities, homes, churches, cabins, industrial buildings, schools and other types of structures around the country have sported the dome's distinctive architecture.

Today, the industry generates increasing interest from cash-strapped school districts in search of both sustainability and community protection in the event of a weather emergency. "For many years, we've recognized the strength of the dome," South says. "It's the curved shape. Put a piece of eggshell in your hand, and it'll snap real easily. But if you put an egg in your hand and squeeze, you can't break it."

The first monolithic dome gymnasium was built at Emmitt (Idaho) High School in 1987, South says. Today, the average cost of most domed gyms is around $125 per square foot. Gymnasium structures generally range in diameter from 120 feet to 250 feet (heights vary according to diameter), and construction typically takes between 12 and 18 months.

Archie's dome (the district has yet to give the gymnasium an official name) might be on the leading edge of a boomlet. Dodge City (Kan.) Community College closed its aging gymnasium in November, citing structural safety issues, and is planning to build a 300-foot-diameter monolithic dome to house a new gymnasium and student activity center this spring.

Less than a 45-minute drive southwest of Dodge City stands another monolithic dome gymnasium, in Fowler, Kan. Completed last spring and funded in part with a $345,000 FEMA grant, the $2.5 million structure houses retractable bleachers that can seat up to 1,000 spectators, plus a band room and a community fitness space. "We're in bleak economic times," Sam Seybold, superintendent of Fowler Unified School District 225, told the Hutchinson News, referring to the 42-foot-high structure with a 132-foot diameter. "To take care of facility needs and promote energy efficiency and keep costs down, this was a no-brainer."

The 152-foot-diameter Eagle Dome, named for the Woodsboro (Texas) Independent School District Eagles, opened in October with 700 chair-back seats. It also is considered a prototype for shelters of last resort in coastal Texas. Funded in part with a $1.5 million FEMA grant, plus bond money approved by voters in 2005, the $2.4 million facility stands 44 feet tall between the district's elementary and middle/high school buildings. The district even had leftover money to upgrade ventilation in an existing gymnasium built in 1957, and to resurface tennis courts and a track.

FEMA has covered up to 75 percent of a monolithic dome's costs (excluding gymnasium elements) in areas prone to tornadoes and hurricanes, according to South. "Most of the buildings that have qualified for the 75 percent have been gyms," he says. "But they have to fit FEMA's criteria on the number of square feet, the number of usable square feet and the number of people in the town."

The structures "are the lowest-cost option for creating windstorm-protected space" above ground, Gregory Pekar, a state hazard mitigation officer in the Texas Department of Public Safety's division of emergency management, told The Christian Science Monitor last May. As proof, reporter Pete Spotts described the fallout from a tornado that blew through Blanchard, Okla., on May 24, 2011. The exterior of a monolithic dome home was surrounded by "a landscape devoid of treetops, with a car shoved up against the structure. The home's windows were blown out, the interior a shambles, but the dome is still standing, even if it has large dings on the outside."

Despite all of its apparent advantages, generating public support for a monolithic dome gymnasium can prove a formidable challenge. Woodsboro ISD superintendent Steven Self admits there were days he wondered if building the Eagle Dome was the right thing to do. "I think some people thought we were crazy," he says. "We had quite a few complaints from citizens who were calling it the 'Woodsboro mosque.' Because it looked different, people were wary of it. I had to call David South several times to get moral support, because there were so many people who were convinced the building wasn't going to work like we were told it would. At one point, I just wanted to say, 'Forget it.'"

One constituent even made objection to the dome a major platform of his school board candidacy. "It's not necessarily an easy sale," Self says, adding that most of Woodsboro's 1,700 residents are "super proud" of the facility now. "These things are not going to win any architectural awards, and that's a drawback. So it takes people who are willing to do something different."

Archie voters were willing, passing a $3 million bond measure for the dome even before receiving confirmation of the FEMA grant. And voters in Pontiac-William-Holliday District #105 in Fairview Heights, Ill. — who had five times failed to pass a bond for an elementary school gymnasium — finally supported the project only when a monolithic dome was introduced into the design plan.

"Once people understand the costs, the energy efficiency and the safety aspects, you've got 90 percent of it licked," South says. "Then people ask, 'Well, what do we want to do about what it looks like?' We can do all kinds of things to make them every bit as nice-looking, if not better-looking, than a standard old gymnasium box."

The domes in Fowler and Archie are wrapped in multicolored brick from the ground level up to where the curved wall meets the arched roof, and the Eagle Dome boasts a warm bronze-colored roof. Leland A. Gray Architects, the Salt Lake City-based firm that Woodsboro ISD hired for the project, warned that white would reveal mold and other natural blemishes over time, while colors such as green and blue tend to fade quickly.

Archie's dome is accented with the bright red and slate gray of the adjoining commons building, so "it doesn't just look like a dome sitting there by itself, dropped down from out of the sky," Smith says. Inside, the ceiling has been dropped and leveled off with acoustical tiles to remove the cavernous feeling and make the environment more intimate for small-town athletics. Some monolithic dome gymnasiums also use interior walls to give the court area a more rectangular look, while others leave the curves for added character.

Even though Archie R-V hired Incite Design Studio in Overland Park, Kan., which specializes in design-build projects, only a handful of builders in the United States currently construct monolithic dome gymnasiums, South says. And he estimates that no more than 40 architects — roughly half of them located in Texas - are well versed in working with the structures.

South has a hard time saying "no," so he holds four annual training sessions at Monolithic headquarters. "I've now built in 52 countries and 49 states," he says, "and I teach the technology to anybody who wants to learn it" — including some contractors who eventually become South's competitors.

South now hopes to build on the success of monolithic gymnasiums to create monolithic indoor sports complexes. Currently in discussions with industry associations and private operators, he is confidently moving in that direction. "I view it as our next major push in the sports industry," he says.

Back in Archie, Smith is thrilled with the district's new gym dome. Three days after opening, the facility hosted the 82nd annual Archie Basketball Tournament, a five-day event showcasing eight boys' and eight girls' teams from around the area that brought hundreds of people into the dome for the first time. He suspects representatives from other school districts will want tours, too. After all, nearly every new monolithic gymnasium that goes up attracts the attention of communities considering one of their own.

Smith's advice is to keep an open mind while weighing all of the financial, safety and sustainability options. And don't be fooled by appearances. "Because they're round, they don't look as big from the outside as they do from the inside," he says. "You don't realize the space that's there. It's amazing how big it is inside. People were even asking us as ours was being constructed, 'Are you sure that's going to be big enough?' Yes, it's big enough."