More State Associations Are Turning to Medical Professionals for Guidance

In November, mere weeks after Texas became the most recent state to create a committee of medical professionals to oversee sports-medicine issues in high school sports, John Alexander, a junior basketball player at Houston's Pasadena Dobie High, collapsed and died on the court during a game. The tragedy, which was eventually attributed to Alexander's enlarged heart, marked the fourth time a Texas high school athlete died of that condition in 2001. And it became a rallying point for the University Interscholastic League's newly formed Medical Advisory Committee.

"We felt it was time to take some serious action and look into our policies," UIL Athletic Director Charles Breithaupt says about the 11-member group comprised of doctors and certified athletic trainers. "These deaths raised the awareness that perhaps there's more that we can do."

Indeed, when football players Steve Taylor from Luling High and Leonard Carter from Houston Lamar High collapsed and died from enlarged hearts one day apart at practices in the scorching August heat - a little more than two weeks after Minnesota Viking offensive tackle Korey Stringer died from heatstroke - state athletic administrators fast-tracked a proposal to create the Medical Advisory Committee. Up until that point, Breithaupt says, the idea for such a committee had been only "slowly simmering." A third Texas football player died of an enlarged heart in September.

"The media at the time said we had three football players who died. We said we had three students who died, who happened to be football players," Breithaupt. "There is no direct correlation between the deaths and football, because those three young men died of enlarged hearts. But some of the panic that came about because of Korey Stringer's death made parents ask whether they should take their kids out of football."

Last year's four student-athlete deaths were the first in Texas since 1999, when three football players died - one from complications associated with an enlarged heart, one from a head injury and one from heatstroke.

Nationally, 20 heat-related football deaths have been reported since 1995 by the National Center for Catastrophic Sports Injury Research, the National Collegiate Athletic Association and the National Federation of State High School Associations; 15 of them were high school players, and two were in junior high. That's a national average of fewer than three heat-related high school football deaths per year.

By comparison, an enlarged heart - also known as left ventricular hypertrophy, which is caused by a thickening of the heart muscle because of an increased workload - has become an all-too-common health problem in young athletes. In addition to the four deaths in Texas, several high school athletes around the country have also died of complications associated with an enlarged heart during the past year.

"We've gotten to the point in this country where you have a lot of people taking care of athletes who don't really know what they're doing," Douglas McKeag, director of Indiana University's Center for Sports Medicine, told The Record of Hackensack, N.J., last summer. Which is why Texas' UIL and other state high school associations like those in Florida, Massachusetts and Pennsylvania have opted to consult experts in the field and create their own sports-medicine committees.

The UIL's Medical Advisory Committee includes two orthopedic surgeons, a cardiologist, a sports medicine specialist, a pediatrician, a neurosurgeon, two certified athletic trainers, a team physician, an emergency medical technician and a member of the Texas High School Coaches Association - all strangers until the UIL brought them together. "I think you'll find in any state that there are doctors willing to give their time, because they played sports in high school, too," Breithaupt says. "We had these guys standing in line to help us."

When UIL's Medical Advisory Committee first met in late September, members divided into subcommittees to evaluate four areas vital to student-athletes' health: heart conditions, head injuries, heat-related issues, and the use and effectiveness of pre-participation physical exams and medical history forms. Any recommendations the committee makes must be approved by the UIL's Legislative Council. "If a group of medical experts recommends something to us, we'd better be very careful if we choose not to follow that recommendation," Breithaupt says.

"The committee was formed in a reactive situation, but we've really tried to make it proactive," says Cary Tanamachi, a Dallas-area orthopedic surgeon who has become the committee's unofficial chair.

Already, the committee has spurred changes in the way the state administers physicals to all student-athletes. Previously, exams were only required of seventh and ninth graders. Beginning in August, however, high school juniors must also take preseason exams if they want to play sports. The forms doctors use to administer the exams have also been changed to reflect new heartcheck parameters defined by the UIL. The extent of some physicians' previous heart exams, Breithaupt says bluntly, went little beyond checking for a pulse.

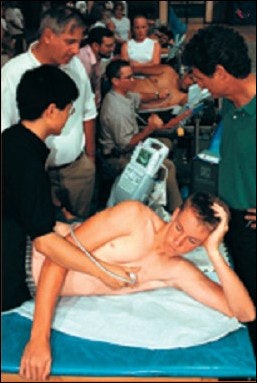

Another result of the Medical Advisory Committee's work is a strategy to provide free echocardiogram screenings for Texas' one million or so high school student-athletes to detect any heart abnormalities or diseases that may exist. At press time, Breithaupt was in the process of confirming corporate sponsorships to help pay for the tests and equipment, and physicians were slated to donate their time to administer the exams. Plans call for setting up the testing at large venues and then busing in student-athletes from area schools. "When you're talking about trying to screen a million athletes, this might be too much to take on all at once," Breithaupt says. "We might just start with one class, and then work our way through the rest."

Tanamachi says the committee also hopes to give schools recommendations for providing parents with details about how to detect if something may be wrong with their children's health, and asking parents to sign a form agreeing to take an active role in the physical well-being of their children as they become student-athletes.

"There may be some things we can have parents look for, as well as have a doctor look for," he says. "Sometimes, these kids want to play at all costs. They say, 'To heck with any health or physical problems.' We want to see if we can change that mind-set by getting parents to better understand these conditions. Even though they may be very much involved in the health of their kids, if they don't know what they're looking for, it doesn't do much good."

By directing the impact of the UIL's Medical Advisory Committee beyond field, court and locker room boundaries, Texas athletic administrators recognize they probably have a better chance than ever of averting the tragedies that befell four Texas football players last year.

"You don't know when a student-athlete will get struck by lightning. And you don't know when a student-athlete will develop an enlarged heart," Breithaupt says. "But you hope that you have the protocols in place and have done everything possible to prevent the death of that young person."