SMU learned early that athletes flourish with the same academic support as other students

Southern Methodist University made national headlines in September 1989, when Mustang football returned to the field following a two-year shutdown of the program for repeat NCAA rules violations. Less noteworthy to most SMU alumni and fans (and certainly the rest of the country) was the launch that same year of the university's Learning Enhancement Center.

But even as the football program struggled to resurrect the national-power status it enjoyed prior to receiving the NCAA's so-called "death penalty" in 1987, the LEC has emerged as a national model in its approach to providing academic support for all students, including student-athletes.

While it wasn't academic scandal that felled the Mustangs, the athletic department's predicament served as a wake-up call for the entire campus, according to Vicki Hill, director of what is now known as the Altshuler Learning Enhancement Center. "When SMU received the death penalty, some forward-thinking administrators said, 'Let's look at ourselves as an institution in general,' " Hill says. "We came about as part of that process of self-scrutiny."

From the start, the LEC's approach has been to provide academic support to all students, integrating athletes with non-athletes. Most important, LEC staff members report to the provost's office, leaving the athletic department out of the academic support business altogether.

That may not seem like a radical concept these days, but it was ahead of the curve in the late '80s. Within the past three years, separate cases alleging academic fraud at Minnesota, Tennessee and Louisiana State have cast a particularly bright spotlight on the issue of academic support for student-athletes. Hill estimates that as many as a third of Division I schools now have academic support services for student-athletes that report to an academic affairs or provost's office, as opposed to the athletic department.

As Virginia's athletic director, one of the last recommendations made by Jim Copeland before departing for SMU eight years ago was to integrate student-athletes within the general student body in terms of academic support. "If we're serious about the 'student' part of 'student-athlete,' I think that's always the best way to do things," Copeland says. "There are other models that work, where the advising unit reports to the athletic director rather than the provost, but I was always uncomfortable with having an academic unit report to me. I think you can avoid a lot of questions and suspicion by having advisors report through an academic line rather than an athletic line."

Hill admits intercollegiate sports participants must deal with uncommon demands, but she feels some academic support programs go so far as to insult student-athletes' intelligence. "Because of the time pressures athletes face and because they're in the public eye, they may need extra people to watch out for them," Hill says. "But we feel our student-athletes are doing well academically because whenever possible, we treat them like students. We give them the same services that non-athletes get. If we're hiring calculus tutors, we're hiring calculus tutors - not calculus tutors for student-athletes. Too often, services that are just for student-athletes have their focus on eligibility rather than ability. I think those programs underestimate the academic capability of their student-athletes."

Nonetheless, the LEC has maintained a longstanding relationship with SMU athletics. Its first home was underneath the stands of Ownby Stadium, the Mustangs' now-defunct football venue, in a primitive enclosure that lacked heat and air conditioning. Before moving two years ago into the brand-new Loyd All-Sports Center, located at the northeast corner of Ford Stadium, an interim LEC location was established in the claustrophobic and disconnected confines of Lettermen Hall, a vacant dormitory that once housed student-athletes.

Over the years, the work conducted at various LEC locations gained widespread respect at SMU, particularly within the athletic department, as Mustang athlete graduation rates consistently topped 80 percent during the 1990s. "In our cramped, undesirable and divided space we had developed a very good track record of academic success with student-athletes," Hill says.

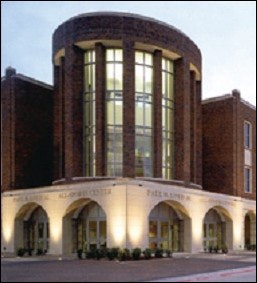

That track record led directly to a partnership opportunity. As construction began on Ford Stadium in 1998, the LEC was sitting on $3 million it had raised toward renovation of a not-yet-identified permanent home. The Loyd Center emerged as an attractive way to parlay those funds into a state-of-the-art space within a new building, which athletics officials eagerly expanded to make room for LEC staff. "We felt that they were critical to our operation," says Copeland. "So we suggested that they bring their whole operation here." According to Hill, the LEC got more value than expected for the $3 million it contributed to the Loyd Center, which now stands three stories tall and boasts 124,000 square feet. "A lot of times when you're renovating, you get almost everything you want," she says. "We got everything we had hoped for in our wildest dreams."

Located on the Loyd Center's second floor, the 14,000-square-foot LEC, which Hill helped design, includes a study room equipped with recessed computer monitors and retractable keyboards, allowing versatile use of desktops and unobstructed visual contact between tutors and students. Smaller rooms accommodate individual study, while open spaces encourage student interaction. A large lobby welcomes visitors, new SMU prospects among them. "The facility is a huge part of what we're able to show prospective student-athletes, but it's also a recruiting tool for non-athletes," Hill says.

Early on, though, there existed concern that the LEC's location in a structure that also houses football, soccer, and track and field offices and locker rooms - not to mention weight training facilities used by all student-athletes - would send a message that the LEC catered first and foremost to student-athletes. "What we've found is that once we get them in here, students kind of forget that they're in the stadium," says Pat Feldman, the LEC's associate director for academic skills. The Loyd Center was designed to provide the LEC with its own entrance and elevator, further lessening the intimidation factor for non-athletes, according to Copeland. "They're made to feel welcome, regardless of whether or not it's an athletic complex," he says.

That said, the LEC does go the extra yard for the Mustangs in some respects. A computer lab is used primarily by student-athletes simply because the economic backgrounds of some players prevent them from owning their own, according to Valerie Ollison, assistant LEC director and one of two full-time staff members dedicated to monitoring the academic performance of student-athletes "SMU really takes pride in graduating its student-athletes, and through academic counseling we're able to track the students and help them make progress toward graduation," says Ollison, adding that some coaches, such as those in football and men's and women's basketball, require their players to report to the LEC.

Athletes in other sports who may be struggling academically are typically identified by their respective coach, in consultation with Ollison, on a case-by-case basis. "Anytime you get the students more comfortable reading, going to study sessions and working with tutors, things are going to get better," says Barb Totzke, associate athletic director for programs and academics.

According to Hill, the LEC has always made room for anyone who needs help. Its new location only makes providing services that much easier for everyone involved. "The student-athletes who are struggling have all the services they would at a center designed just for student-athletes. At the same time, academically stronger student-athletes have access to things that might not be available from a support service designed only to keep marginal student-athletes eligible," she says. "We want more for and from our student-athletes than that."